Jellyfish: The Next King of the Sea

As the world’s oceans are degraded, will they be dominated by jellyfish?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Northeast-Pacific-sea-nettles-Monterey-Bay-Aquarium-631.jpg)

On the night of December 10, 1999, the Philippine island of Luzon, home to the capital, Manila, and some 40 million people, abruptly lost power, sparking fears that a long-rumored military coup d’état was underway. Malls full of Christmas shoppers plunged into darkness. Holiday parties ground to a halt. President Joseph Estrada, meeting with senators at the time, endured a tense ten minutes before a generator restored the lights, while the public remained in the dark until the cause of the crisis was announced, and dealt with, the next day. Disgruntled generals had not engineered the blackout. It was wrought by jellyfish. Some 50 dump trucks’ worth had been sucked into the cooling pipes of a coal-fired power plant, causing a cascading power failure. “Here we are at the dawn of a new millennium, in the age of cyberspace,” fumed an editorial in the Philippine Star, “and we are at the mercy of jellyfish.”

A decade later, the predicament seems only to have worsened. All around the world, jellyfish are behaving badly—reproducing in astonishing numbers and congregating where they’ve supposedly never been seen before. Jellyfish have halted seafloor diamond mining off the coast of Namibia by gumming up sediment-removal systems. Jellies scarf so much food in the Caspian Sea they’re contributing to the commercial extinction of beluga sturgeon—the source of fine caviar. In 2007, mauve stinger jellyfish stung and asphyxiated more than 100,000 farmed salmon off the coast of Ireland as aquaculturists on a boat watched in horror. The jelly swarm reportedly was 35 feet deep and covered ten square miles.

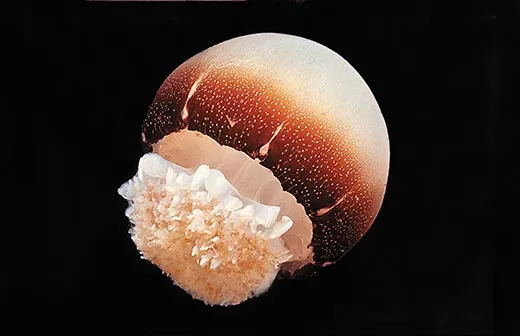

Nightmarish accounts of “Jellyfish Gone Wild,” as a 2008 National Science Foundation report called the phenomenon, stretch from the fjords of Norway to the resorts of Thailand. By clogging cooling equipment, jellies have shut down nuclear power plants in several countries; they partially disabled the aircraft carrier USS Ronald Reagan four years ago. In 2005, jellies struck the Philippines again, this time incapacitating 127 police officers who had waded chest-deep in seawater during a counterterrorism exercise, apparently oblivious to the more imminent threat. (Dozens were hospitalized.) This past fall, a ten-ton fishing trawler off the coast of Japan capsized and sank while hauling in a netful of 450-pound Nomura’s jellies.

The sensation of getting stung ranges from a twinge to tingling to savage agony. Victims include Hudson River triathletes, Ironmen in Australia and kite surfers in Costa Rica. In summertime so many jellies mob the waters of the Mediterranean Sea that it can appear to be blistering, and many bathers’ bodies don’t look much different: in 2006, the Spanish Red Cross treated 19,000 stung swimmers along the Costa Brava. Contact with the deadliest type, a box jellyfish native to northern Australian waters, can stop a person’s heart in three minutes. Jellyfish kill between 20 and 40 people a year in the Philippines alone.

The news media have tried out various names for this new plague: “the jellyfish typhoon,” “the rise of slime,” “the spineless menace.” Nobody knows exactly what’s behind it, but there’s a queasy sense among scientists that jellyfish just might be avengers from the deep, repaying all the insults we’ve heaped on the world’s oceans.

“Jellyfish” is a decidedly unscientific term—the creatures are not fish and are more rubbery than jamlike—but scientists use it all the same (though one I spoke with prefers his own coinage, “gelata”). The word “jellyfish” lumps together two groups of creatures that look similar but are unrelated. The largest group includes the bell-shaped beings that most people envision when they think of jellyfish: the so-called “true jellies” and their kin. The other group consists of comb jellies—ovoid, ghostly creatures that swim by beating their hairlike cilia and attack their prey with gluey appendages instead of stinging tentacles. (Many other gelatinous animals are often referred to as jellyfish, including the Portuguese man-of-war, a colony of stinging animals known as a siphonophore.) All told, there are some 1,500 jellyfish species: blue blubbers, bushy bottoms, fire jellies, jimbles. Cannonballs, sea walnuts. Pink meanies, a.k.a. stinging cauliflowers. Hair jellies, a.k.a. snotties. Purple people eaters.

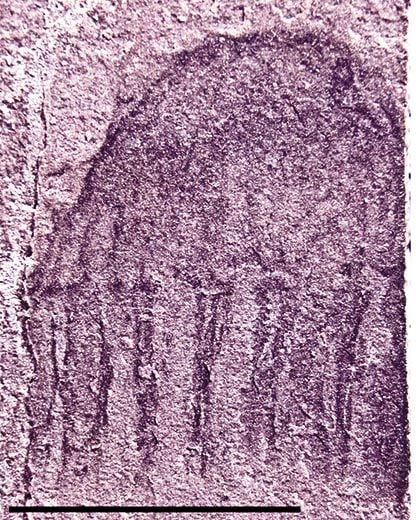

The bell-shaped jellies—distantly related to corals and anemones—launched their lifestyle long, long ago. Exquisite jellyfish fossils found recently in Utah display reproductive organs, muscle structure and intact tentacles; the jelly fossils, the oldest discovered, date back more than 500 million years, when Utah was a shallow sea. By contrast, fish evolved only about 370 million years ago.

The descendants of those ancient jellies haven’t changed much. They are boneless and bloodless. In their domelike bells, guts are squished beside gonads. The mouth doubles as an anus. (Jellies are also brainless, “so they don’t have to contemplate that,” one jelly specialist says.) Jellies drift at the mercy of the currents, though many also propel themselves by contracting their bells, pushing water out, while others—such as the upside-down jellyfish and the flower hat, with its psychedelic lures—can recline on the seafloor. They absorb oxygen and store it in their jelly. They can sense light and certain chemicals. They can grow quickly when there’s food around and shrink when there isn’t. Their tentacles, which reach up to 100 feet long in some species, are covered with cells called nematocysts that fire tiny poison harpoons, enabling the animals to immobilize krill, larval fish and other prey without risking their mushy bodies in a struggle. Yet if a sea turtle bites off a hunk, the flesh regenerates.

A breeding jellyfish can spit out unfertilized eggs at a prodigious rate: one female sea nettle may spew as many as 45,000 per day. To maximize the chances of sperm meeting egg, millions of moon jellies of both sexes assemble in one place for a gamete-swapping orgy.

Chad Widmer is one of the world’s most accomplished jellyfish cultivators. At the Monterey Bay Aquarium in California, he is lord of the “Drifters” exhibit, a slow-motion realm of soft edges, rippling flute music and sapphire light. His left ankle is crowded with tattoos, including Neptune’s trident and a crystal jellyfish. A senior aquarist, Widmer labors to figure out how jellyfish thrive in captivity—a job that involves untangling tentacles and plucking gonads until his arm is swollen with venom.

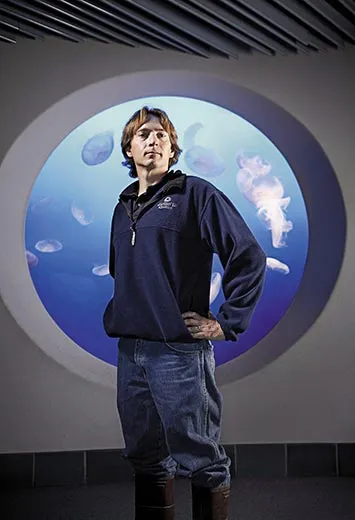

Widmer has bred dozens of jellyfish species, including moon jellies, which resemble animated shower caps. His signature jelly is the Northeast Pacific sea nettle, displayed by the score in a 2,250-gallon exhibit tank. They are orange and incandescent, like dollops of lava, and when they swim against the current they look like glowing meteors streaming to Earth.

The waters of Monterey Bay have not been spared from the gelatinous woes said to be sweeping the oceans. “It used to be that everything had a season,” Widmer says. Spring was the time for lobed comb jellies and crystal jellies to arrive. But for the past five years or so, those species seem to be materializing almost at random. The orange spotted comb jelly, which Widmer nicknamed the “Christmas jelly,” no longer peaks in December; it haunts the shoreline practically year-round. Black sea nettles, once seen mostly in Mexican waters, have started appearing off Monterey. Last August, millions of Northeast Pacific sea nettles bloomed in Monterey Bay and clogged the aquarium’s seawater intake screen. The nettles typically retreat by early winter. “Well,” Widmer informs me gravely on my February visit, “they’re still out there.”

It’s hard to tell what may be causing jellyfish to proliferate. The fishing industry has depleted populations of big predators such as red tuna, swordfish and sea turtles that feed on jellyfish. And when small, plankton-eating fish such as anchovies are overharvested, jellies flourish, gorging on plankton and reproducing to their hearts’ content (if they had hearts, that is).

In 1982, when the Black Sea ecosystem was already weakened by anchovy overfishing, the warty comb jelly (Mnemiopsis leidyi) arrived; a species native to the East Coast of the United States, it was most likely carried across the Atlantic in a ship’s ballast water. By 1990, there were some 900 million tons of them in the Black Sea.

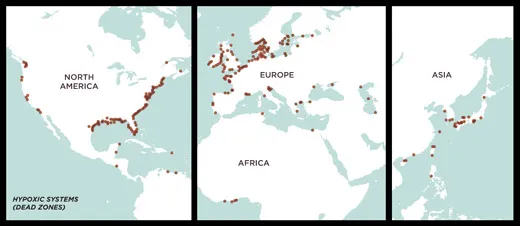

Pollution, too, may be fueling the jelly frenzy. Jellyfish succeed in all sorts of fouled conditions, including “dead zones,” where rivers have pumped fertilizer runoff and other materials into the ocean. The fertilizer fuels phytoplankton blooms; after the phytoplankton die, bacteria decompose them, hogging oxygen; the oxygen-depleted water then kills or forces out other marine creatures. The number of coastal dead zones has doubled every decade since the 1960s; there are now roughly 500. (Oil can kill jellyfish, but no one knows how jellyfish populations in the Gulf of Mexico will fare in the long run after the BP oil spill.)

Carbon-based air pollution may be another factor. Since the Industrial Revolution, the amount of carbon in the atmosphere from burning fossil fuels and wood as well as from other enterprises has risen by some 36 percent. That contributes to global warming, which, some researchers speculate, may benefit jellyfish at the expense of other marine animals. Moreover, carbon dioxide dissolves in seawater to form carbonic acid—a major threat to marine life. As the seas become more acidic, scientists say, ocean water will begin to dissolve animal shells, stunt coral reefs and disorient larval fish by skewing their sense of smell. Jellies, meanwhile, may not even be inconvenienced, according to recent studies by Jennifer Purcell of Western Washington University.

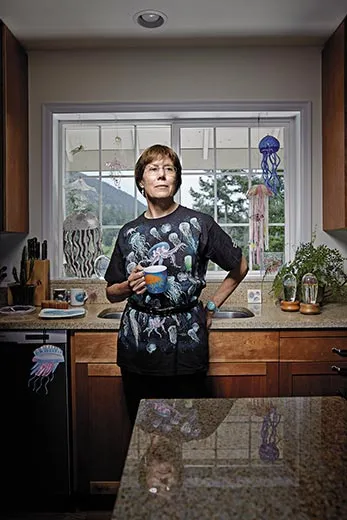

Purcell and a graduate student, Amanda Winans, decided to breed moon jellyfish in water with the staggering acid levels that some scientists say will prevail in the years 2100 and 2300. “We took it to very severe acid, using the worst predictions,” Purcell says. The jellyfish reproduced with abandon. She has also conducted experiments that lead her to suspect that many jellies reproduce better in warmer water.

With the world’s human population expected to increase 32 percent by 2050, to 9.1 billion, a number of environmental conditions that favor jellyfish are predicted to become more common. Jellyfish reproduce and move into new niches so rapidly that even within 40 years, some experts predict “regime shifts” in which jellyfish assume dominance in one marine ecosystem after another. Such shifts may have already occurred, including off Namibia, where, after years of overharvesting, the once fecund waters of the Benguela current now contain more jellyfish than fish.

Steven Haddock, a zooplankton scientist at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI), is concerned that researchers and the news media may be overreacting to a few isolated jelly outbreaks. Not enough is known about historical jelly abundances to distinguish between natural fluctuation and long-term change, he says. Are there really more of the creatures, or are people simply more prone to notice and report them? Are the jellyfish changing, or is our perspective? A self-described “jelly hugger,” Haddock worries that jellyfish are taking the blame for messing up the seas when we’re the ones causing the damage. “I just wish that people had the perception that jellyfish are not the enemy here,” Haddock says.

Purcell, who sports jellyfish earrings the day I meet her in Monterey, says she is disgusted by what she sees as humanity’s efforts to exploit the ocean, filling it with fish farms and oil wells and fertilizer. Compared with fish, jellies are “better feeders, better growers, more tolerant of all kinds of things,” she told me, adding of the marine environment: “I think it’s entirely possible we’ve made things better for jellyfish.” Part of her likes the idea of unruly jellies causing a commotion and foiling our plans. She’s cheering for them, almost.

Widmer’s lab at the Monterey Aquarium is dominated by bubbling lime-green columns of algae, which he feeds to brine shrimp, which he then feeds to jellyfish. The algae come in six other “flavors,” but he says he prefers the green type for its mad scientist aesthetic. The room is full of jellyfish tanks ranging in size from salad bowls to wading pools. The containers rotate slowly, creating a current. “Let’s feed!” Widmer cries. He scrambles up and down stepladders, squirting a turkey baster of pink krill into this tank and that.

Toward the back of the lab, haggard orange sea nettles stumble along the bottom of their tank, their bells brownish and transparent, their tentacles torn. These, Widmer says, have been taken out of the public display and retired. “Retired” is Widmer’s euphemism for “about to be snipped up with fabric scissors and fed to other jellies.”

He calls his prize specimens “golden children.” He speaks to them in cooing tones usually reserved for kittens. One tank holds the petite but striking purple-lipped cross jellies, which Widmer retrieved from Monterey Bay. The species has never been bred in captivity before. “Oh, aren’t you cute!” he trills. The other golden child is a small brown smudge on a pane of glass. This, he explains, dabbing artistically at the smudge’s edges with a paintbrush, is a colony of lion’s mane jellyfish polyps.

When jellyfish sperm and egg meet, the fertilized egg forms a free-swimming larva, what Widmer describes as “a fuzzy ciliated tic tac.” It whizzes around before landing on a sponge or other seafloor fixture. There it morphs into a weedy little polyp, an intermediate form that can reproduce asexually. And then—well, sometimes nothing happens for a good long while. A jellyfish polyp can sit dormant for a decade or more, biding its time.

When ocean conditions become ideal, however, the polyp starts to “strobilate,” or bud off new jellyfish, a process Widmer shows me under a microscope. One polyp looks as if it is balancing a stack of Frisbees on its head. The tower of tiny discs pulses slightly. Eventually, Widmer explains, the top one will fly off, like a clay pigeon at a shooting range, then the next one, and the next. Sometimes dozens of discs launch, each disc a baby jellyfish.

To test the impact of warming oceans on polyp productivity, Widmer assembled a series of incubators and seawater baths. If he heated each a few degrees warmer than the last, what would the jellyfish do? At 39 degrees Fahrenheit, the polyps generated, on average, about 20 teeny jellyfish. At 46 degrees, roughly 40. The polyps in 54-degree seawater birthed some 50 jellies each, and one made 69. “A new record,” Widmer says, awed.

To be sure, Widmer has also found that some polyps can’t produce young at all if placed in waters significantly warmer than their native range. But his experiments, which confirm research on other jellies done by Purcell, also lend some credence to anxieties that global warming may induce jelly extravaganzas.

Two events ultimately stalled the Mnemiopsis invasion in the Black Sea. One was the fall of the Soviet Union: in the ensuing chaos, some farmers ceased fertilizing their fields and water quality improved. The other was the accidental introduction of a second exotic jellyfish that happened to have a taste for Mnemiopsis.

In lieu of dismantling superpowers or importing invasive species, countries have adopted jelly-proofing strategies. South Korea recently released 280,000 native, jelly-eating filefish along the coast of Busan. Spain dispatched indigenous loggerhead sea turtles off Cabo de Gata. Japanese fishermen hack at the giant Nomura’s with barbed poles. Mediterranean beaches have organized jellyfish hot lines, spotter boat armadas and airplane flyovers; the slimy troublemakers are sometimes sucked up by garbage scows, carted off by backhoes or used for fertilizer. Bathers in the worst areas are advised to wear full-body Lycra “stinger suits” or pantyhose or to smear themselves with petroleum jelly. Most sting-treatment products feature vinegar, the best remedy for jelly venom.

When, nearly two decades ago, Daniel Pauly, a fisheries biologist at the University of British Columbia, started warning of the dangers of overfishing, he liked to alarm people and say we would end up eating jellyfish. “It’s not a metaphor anymore,” he says today, pointing out that not only China and Japan but also the U.S. state of Georgia have commercial jellyfish operations, and there’s talk of one starting in Newfoundland, among other places. Pauly himself has been known to nibble jellyfish sushi.

About a dozen jellyfish varieties with firm bells are considered desirable food. Stripped of tentacles and scraped of mucous membranes, jellyfish are typically soaked in brine for several days and then dried. In Japan, they are served in strips with soy sauce and (ironically) vinegar. The Chinese have eaten jellies for 1,000 years (jellyfish salad is a wedding banquet favorite). Lately, in an apparent effort to make lemons into lemonade, the Japanese government has encouraged the development of haute jellyfish cuisine—jellyfish caramels, ice cream and cocktails—and adventuresome European chefs are following suit. Some enthusiasts compare the taste of jellyfish to fresh squid. Pauly says he’s reminded of cucumbers. Others think of salty rubber bands.

The main edible variety in U.S. waters, cannonball jellies, are found on the Atlantic Coast from North Carolina to Florida and in the Gulf of Mexico. They scored quite high on a “hedonic scale” of color and texture in a study led by Auburn University. Another scientific paper hailed jellyfish flesh—which is 95 percent water, a few grams of protein, the barest hint of sugar, and, once dried, only 18 calories per 100-gram serving—as “the ultimate modern diet food.”

The research vessel Point Lobos heaves in the swells of Monterey Bay. After a two-hour ride from shore, the engine idles as a crane lowers the Ventana, an unmanned submarine stocked with a dozen glass collecting jars, into the water. As the submarine begins its descent into the canyon, its cameras feed footage to computer monitors in the boat’s dark control room. Widmer and other scientists watch from a semicircle of armchairs. Widmer is allotted only a few trips on the MBARI submarine each year for his research; his eyes are shining with anticipation.

On the screens we see the bright green surface water darken by degrees to deep purple, then black. White flecks of detritus called marine snow rush past, like a star field in warp speed. The submarine drops 1,000, 1,500, 5,000 feet. We are en route to what Widmer has modestly named the Widmer Site, a jellyfish mecca on the lip of an undersea cliff.

Our spotlight illuminates a Gonatus squid, which clenches itself into an anxious red fist. Giant gray-green Humboldt squid sail by, like the ghosts of spent torpedoes. Glimmering beings appear. They seem to be constructed of spider webs, fishing line and silk, soap bubbles, glow sticks, strands of Christmas lights and pearls. Some are siphonophores and gelatinous organisms I’ve never seen before. Others are tiny jellyfish.

Every now and then, Widmer squints at an iridescent speck, and—if it isn’t too delicate, and the gonads look ripe—asks the pilot of the remote-controlled sub to give chase. “I don’t know what it is, but it looks promising,” he says. We bear down on jellyfish the size of jingle bells and gumdrops, slurping them up with a suction device.

“Down the tube!” Widmer cries in triumph.

“In the bucket!” the pilot agrees.

The whole boat crew pauses to stare at the screen and marvel at a piece of kelp studded with fuzzy pink anemones. We snatch a jelly here, a jelly there, including a mysterious one with a strawberry-colored center, always keeping a sharp eye out for polyps.

The submersible sails over the wreck of a blue whale, a gigantic rockfish curled up like a cat beside the great skull. We pass a frilly albino sea cucumber and a Budweiser can. We see squat lobsters and spot prawns, bleached sea stars, black owl fish, bouncy coils of eggs, a pale pink orb with tarantula-like legs, lemon-yellow mermaid’s purses, English sole, starry flounders and the purple bullet shapes of sharks. The California sunshine seems dismal in comparison.

When the submarine surfaces, Widmer quickly packs his tiny captives into chilled Tupperware containers. The strawberry jelly begins to languish almost immediately, as the sunlight disintegrates the red porphyrin pigment in its bell; soon it will be floating upside down. A second unknown specimen with pinwheel-shaped gonads looks perky enough, but we have caught only one, so Widmer will not be able to breed it for public display. He hopes to retrieve more on the next trip.

He has, however, managed to corral half a dozen Earleria corachloeae, a species he recently discovered. He named it after his two young landlocked nieces in Wichita, Kansas—Cora and Chloe. Widmer produces a YouTube series for them called “Tidepooling With Uncle Chad,” which introduces ocean wonders—sea turtle nests, bull kelp trumpets, snail racetracks—he wants them to know.

Two days later, the E. corachloeae produce a smattering of eggs like grains of fine beach sand. He will dote on his captives until they die or go on display. They are officially “golden children.”

Abigail Tucker is a staff writer. John Lee’s photographs have run in Smithsonian articles about tomatoes and John Muir.