How Star Trek Helped NASA Dream Big

And how NASA helped Star Trek stick around.

:focal(1138x1030:1139x1031)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20/2d/202d69a8-2a22-415d-9212-a39ae73f8265/06c_fm2021_leonardnimoytributeiss042e291952_live.jpg)

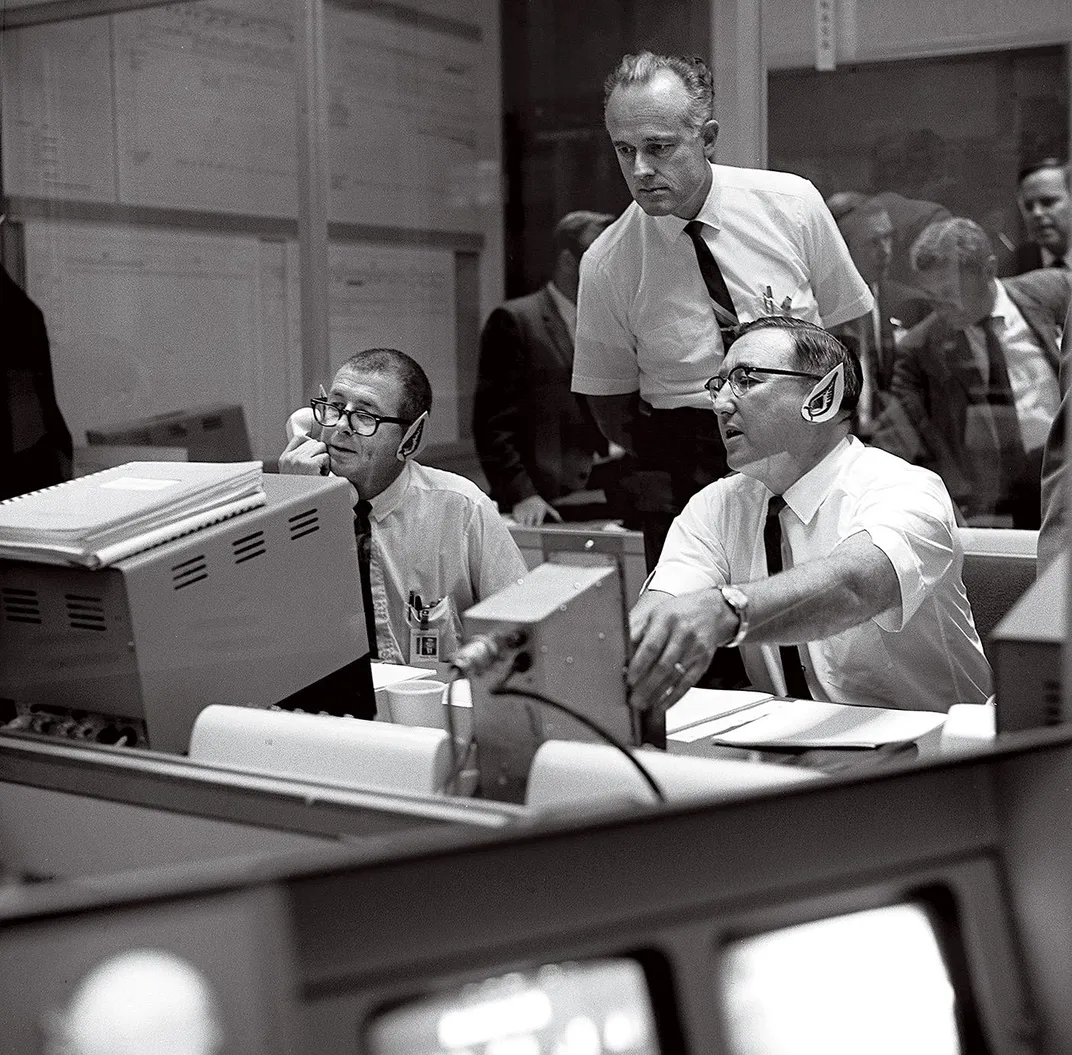

On the afternoon of January 27, 1967, the three crew members of the first Apollo mission left the transfer van that took them to the launch pad at Cape Canaveral. There, astronauts Roger Chaffee, Gus Grissom, and Ed White entered the command module and began a “plugs out” test (that is, with the spacecraft detached from all umbilicals and external power sources) of the launch vehicle and spacecraft designed to carry them on their mission.

At 6:31 p.m., a spark ignited in the lower equipment bay of the spacecraft. The atmosphere inside was 100 percent oxygen. The astronauts didn’t have a chance.

The evening before the fire that claimed the lives of these three men, loyal viewers had tuned in for “Tomorrow Is Yesterday,” the 19th episode of a four-month-old TV show called Star Trek.

Set in the 23rd century, the groundbreaking series had attracted a loyal following of viewers who relished its serious approach to the genre of science fiction. Among the subset of fans who most valued this element of the show were some of the key people working in America’s space program, who saw the Starship Enterprise and its crew of high-minded explorers as the future embodiment of what they hoped to achieve. When the Apollo 1 tragedy occurred, people had been flying into space for less than seven years. Spaceflight was new and dangerous, and here was a show that made it feel routine. Star Trek offered hope to a nation and a space program in a moment when both had reason to doubt they would ever reach the moon, never mind the “new life and new civilizations” promised in the show’s opening-credits monologue. By 1967 NASA needed Star Trek—and, as it later turned out, Star Trek needed NASA.

Alberta Moran was the assistant to John F. Clark, then director of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. She was also one of the founders of the National Space Club. Composed of industry and government representatives along with educational institutions and the press, the National Space Club seeks to promote leadership in the burgeoning new field of astronautics. One way they did that was to sponsor the Goddard Memorial Dinner. Held in Washington, D.C., the annual dinner is named after American space pioneer Robert H. Goddard and recognizes persons and institutions that have made outstanding contributions to space science and technology during the previous year.

“We were at my house getting the invitation list together for the [1967] Goddard Dinner,” recalls Moran. “Penny, my oldest daughter came in and said, ‘Why don’t we invite somebody from Star Trek?’ ”

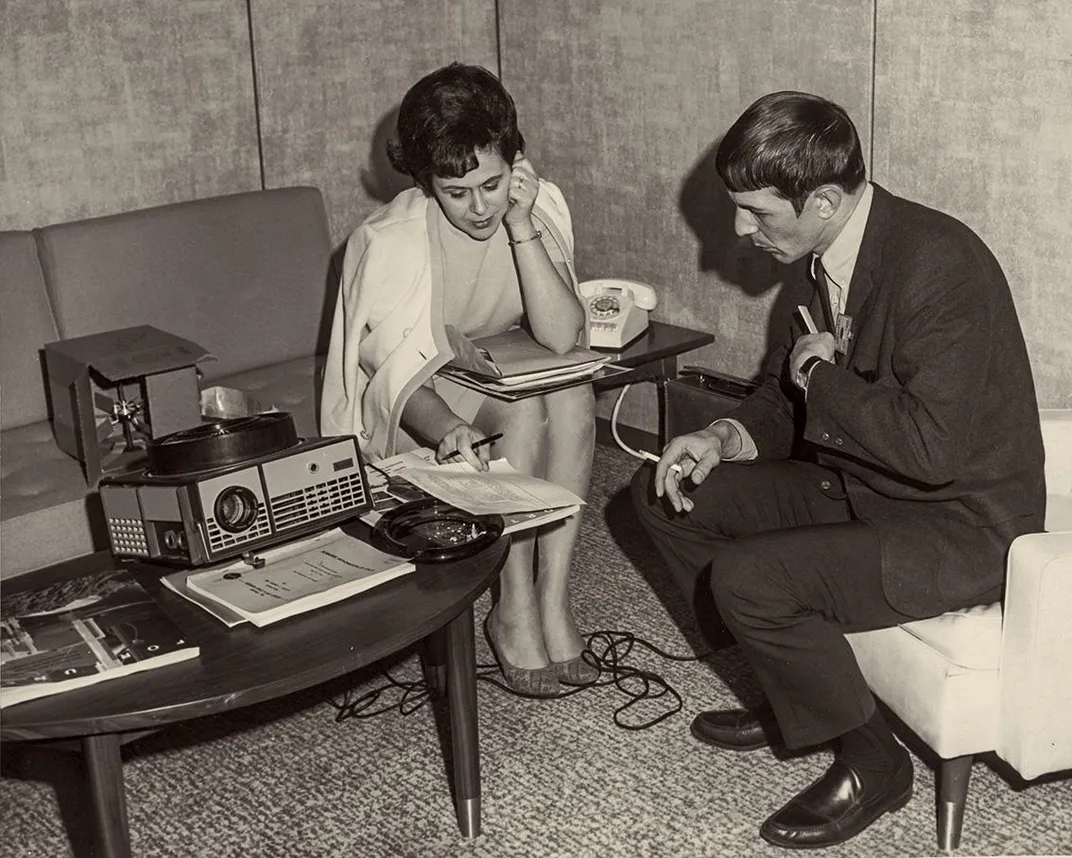

On March 14, the day before the Goddard Dinner, Leonard Nimoy—who played the unflappable half-human, half-Vulcan science officer, Mr. Spock, who had quickly become the series’ most popular character—landed at Dulles International Airport about 30 miles west of Washington. When she went to pick up Nimoy, Moran brought Penny along with two of her daughters’ friends. The three rabid Star Trek fans got to share a car with one of the program’s newly minted stars for the roughly hour-long drive downtown.

The next morning, Nimoy’s wife Sandy joined him for a tour of the Goddard Space Flight Center. The visitors were shocked by how much of Goddard’s workforce had turned out to greet them. In a 1967 letter to Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry, Nimoy wrote: “This was the first real taste that I had of the NASA attitude towards Star Trek.”

The dinner was that evening. All the top managers from NASA and its contractors were at the black tie affair. Barely six weeks after the Apollo 1 fire, the mood among everyone that evening was tempered by the realization that the moon landing would be delayed. Some even speculated that the Apollo program might be canceled altogether.

After the reception, the Nimoys found themselves seated at a table with space luminaries. In addition to astronaut John Glenn, the first American to orbit the Earth, those seated at the dais included NASA Administrator James Webb, Robert Goddard’s widow, and the evening’s speaker: Vice President Hubert Humphrey.

After Humphrey’s speech, other guests waited patiently to share a moment with Nimoy. “They were all most cordial,” the actor wrote in the letter to Roddenberry. “All of them wanted autographs and pictures for themselves and their children.”

That evening, people looked beyond what had happened with the Apollo fire. While Nimoy shook hands and signed autographs, those attending the dinner saw not just the actor, but Mr. Spock, a representative from the future who knew that what they were doing in their century might have been painful but was necessary for them to move forward in exploring the final frontier of space. Nimoy wrote to Roddenberry: “I do not overstate the fact when I tell you that the interest in the show is so intense, that it would almost seem they feel we are a dramatization of the future of their space program, and they have completely taken us to heart…they are, in fact, proud of the show as though in some way it represents them.”

That wasn’t such a far-fetched notion. A couple of years earlier, when Roddenberry had been seeking meetings with esteemed members of the aerospace community to discuss ideas for his wild-sounding TV show, it had helped immensely that Roddenberry could talk shop. He’d flown B-17s during World War II, and had then spent about three years as a pilot for Pan American World Airways.

An example of how the aerospace industry directly influenced Star Trek appears in the classic Season Two episode “The Trouble With Tribbles,” first aired on December 29, 1967. In this episode, “Space Station K-7” is overrun by cute, furry animals who eat and breed uncontrollably. The principal elements of the space station as it appears in the episode were first depicted in a 1959 report by Douglas Aircraft that outlined the operational requirements of an extendable orbiting space station. Space Station K-7 was practically a Douglas design.

Other aerospace companies also contributed ideas. Representatives from General Electric’s aerospace division and Caltech’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory toured the Star Trek sets and answered questions from cast members. These meetings were invaluable, but Roddenberry wanted Star Trek to have the imprimatur of NASA itself.

In a 1966 memo, Roddenberry wrote that a public information specialist at NASA’s Western Operations Office in Santa Monica “was very interested in Star Trek and most anxious to provide us with all sorts of help including stock footage, valuable models, animation, technical advice, even access to some NASA labs and proving grounds.”

The Air Force’s elite Aerospace Research Pilot School invited Roddenberry and the show’s cast to visit their facilities and attend graduation exercises at Edwards Air Force Base. Roddenberry showed up. In October 1968, actor DeForest Kelley, who played cantankerous Enterprise Chief Medical Officer Leonard “Bones” McCoy, was drafted to comfort the astronauts of Apollo 7, the first crewed Apollo mission. When Wally Schirra, Donn Eisele, and Walt Cunningham developed colds during their 10 days in space, Kelley sent the crew a telegram reading: “I do not make house calls but under the circumstances, I am pleased to beam aboard and take care of the common cold. (Signed) Bones.”

There was even an effort to try to get astronaut Alan Shepard to appear on the show. Shepard, the first American to travel into space during his historic May 5, 1961 suborbital flight and the fifth man to walk on the moon, was asked to play a minor role in the series. Sadly, the deal never materialized.

In a March 1968 letter to James Webb, NASA’s administrator, Roddenberry expressed his appreciation for NASA’s support. “I have never received friendly and efficient cooperation anywhere near that provided by your Agency,” he wrote.

Historic Enough for the Smithsonian

At the Goddard dinner in March 1967, while Nimoy posed for pictures and signed autographs, another individual stood nearby. Richard Preston, an administrative officer with the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum, was waiting his turn to deliver an important message to Nimoy: The Smithsonian wanted a copy of the show’s pilot episode. Or rather, its second pilot episode.

Roddenberry had famously tried to sell his series to NBC executives with a 1964 pilot called “The Cage.” William Shatner wasn’t in it, and Nimoy laughs and grins as Mr. Spock—a very different imagining of the wry but sober character who in his mature incarnation would become so beloved.

NBC suits found the whole thing slow, talky, and “too cerebral.” But they took the unprecedented step of commissioning a second pilot. “Where No Man Has Gone Before” added Shatner to the cast as Enterprise Captain James T. Kirk, among other major changes. It was this revised Star Trek that NBC and later, the Smithsonian, approved.

No other show in the history of television had ever had its pilot requested by the Smithsonian. But Preston was just the messenger. The request had come from Frederick C. Durant III, a naval aviator, test pilot, and rocket engineer who in 1965 had become assistant director of astronautics for the National Air and Space Museum.

Durant’s credentials for the post were impeccable. Poor health prevented him from being deployed overseas during World War II, but he served with honor on the homefront, as a flight instructor teaching new cadets how to make carrier landings in the Great Lakes. After the war, he became an ardent promoter of spaceflight, holding posts as a consultant and engineer in various research labs and the Department of Defense. In 1953 he’d been elected president of the American Rocketry Society, one of several positions he held through which he befriended scientist and author Arthur C. Clarke and German rocket pioneer Wernher von Braun, among other luminaries.

An avid science fiction fan, Durant watched Star Trek with interest and soon struck up a correspondence with Roddenberry. Preston, an aide to Durant at the time, wrote to Roddenberry in 1967: “We believe the Star Trek pilot would be a valuable addition to the archives of the National Air and Space Museum. Science Fiction forms a definite segment of astronautics chronology.” On August 28, 1967, Roddenberry formally presented a 16mm color print copy of “Where No Man Has Gone Before” to S. Paul Johnston, director of the National Air and Space Museum.

Fan, Short for Fanatic

Just a few days before the Goddard Dinner, Roddenberry received word from NBC that Star Trek would be renewed for a second season. Paul L. Klein, vice president of audience measurement for NBC, wrote in the May 27, 1967 issue of TV Guide: “Star Trek is the only science-fiction show on television with a scientific basis. I was instrumental in recommending Star Trek for the NBC schedule and have been one of the show’s staunchest supporters during the agony of renewal time. Messrs. Roddenberry, Coon and the whole Star Trek staff have deserved the public’s approval, NBC’s faith in them, and, as topping to the cake, were just recently honored by the National Space Club in Washington for their scientific validity.”

When Star Trek debuted, NBC gave it the coveted time slot of 8:30 p.m. on Thursday. During the second season, the show was moved to Fridays, a less desirable slot particularly for a show beloved by high school and college students.

“We were making out fine where we were,” said Roddenberry in an August 13, 1967 interview, “but now we may lose many of the young people who’ve been watching, because Friday is the night they like to go out.”

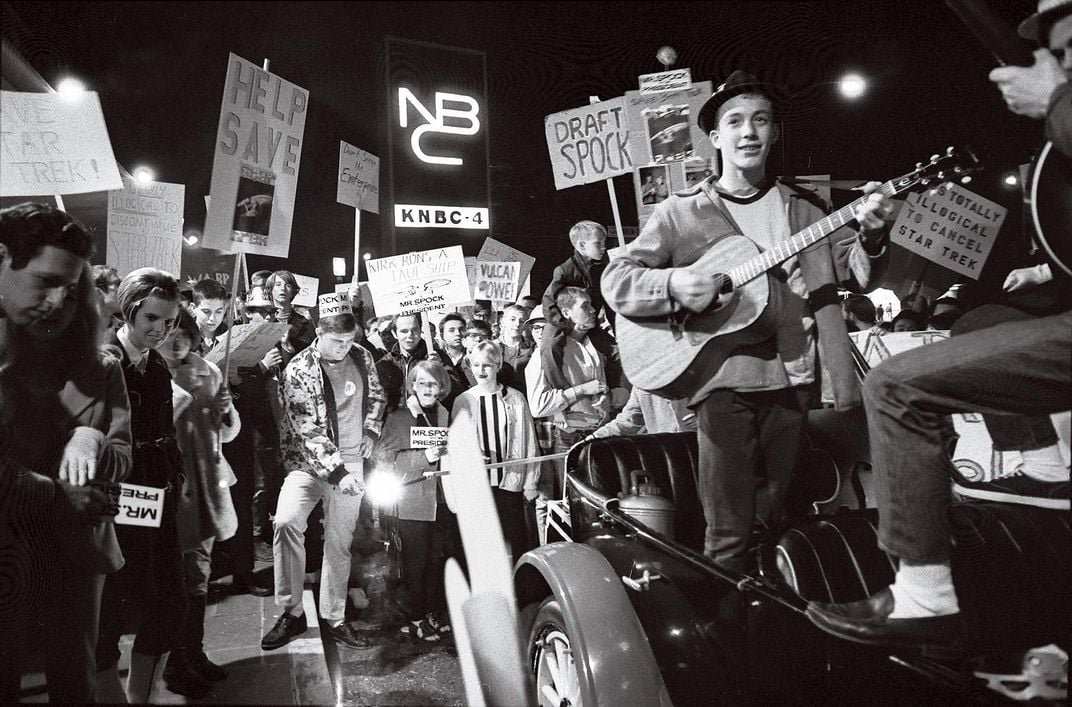

Still, fans would not let the show die. By late 1967, when it looked like the series would not be able to secure a third season, a massive letter writing campaign helped generate a lot of attention.

“Star Trek is the ‘in’ show with the people who work at NASA, Caltech, and the space plants,” said Roddenberry during an interview that year. Boasting that NBC received some 4,500 pro-Trek letters per week, Roddenberry went on to say that, “we get letters from curators of museums and college presidents, all of whom appreciate our serious attempt to portray what space travel will be like.”

On March 1, 1968 at 9:28 p.m. following the first-run airing of the Star Trek episode “The Omega Glory,” an NBC announcer assured viewers that the series would continue to be seen on television that fall. To announce a renewal on the air like this was unusual, but then, so was the kind of attention Star Trek engendered.

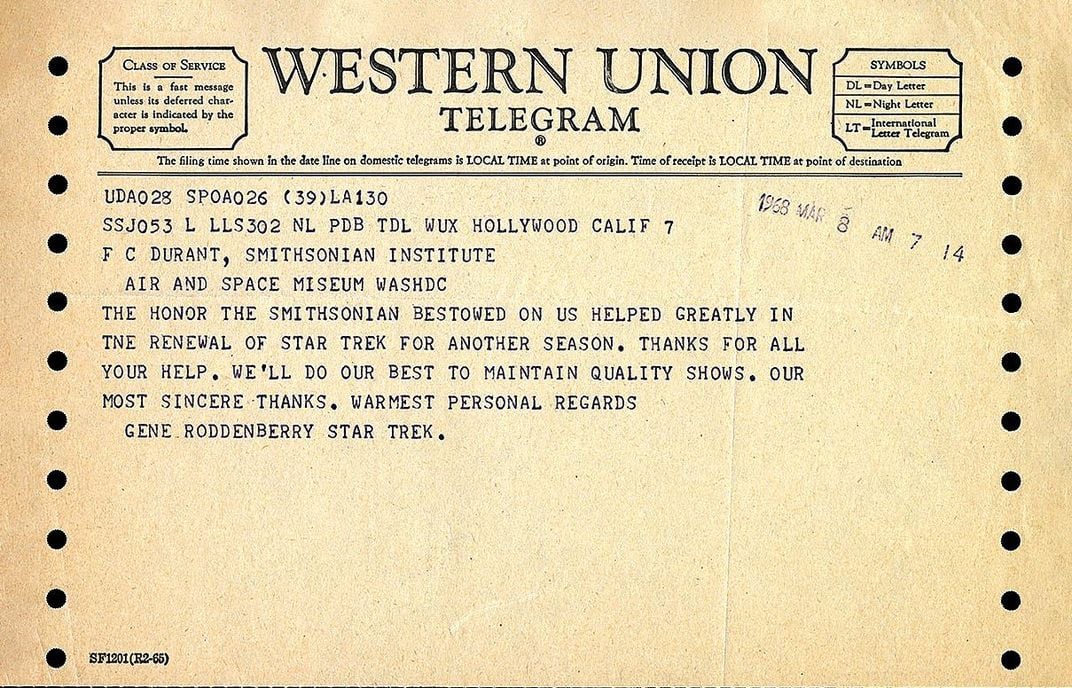

Seven days after NBC announced the third-season renewal, Roddenberry sent the following telegram to Durant at the Smithsonian:

THE HONOR THE SMITHSONIAN BESTOWED ON US HELPED GREATLY IN THE RENEWAL OF STAR TREK FOR ANOTHER SEASON. THANKS FOR ALL YOUR HELP. WE’LL DO OUR BEST TO MAINTAIN QUALITY SHOWS. OUR MOST SINCERE THANKS. WARMEST PERSONAL REGARDS

—GENE RODDENBERRY, STAR TREK

It was not a complete triumph. For its third season, Star Trek would have its budget slashed, resulting in notably diminished production value. And it would remain on Friday nights, now in an even less favorable time slot: 10 p.m. Roddenberry knew that the third season would be the last—at least for a while.

In recalling the initial lifespan of his brainchild, Roddenberry said: “[The U.S. was] just getting into space. When we made our first episode, we hadn’t even been to the moon. Then Star Trek came along and said, ‘Hey, we made it!’ It’s a program that said there is basic intelligence and goodness and decency in the human animal that will triumph over these things.”

While fans almost unanimously agree that Star Trek’s third season saw a regrettable decline in quality, those final 24 episodes are what made the series’ run long enough for the show to live on in syndication, to be discovered by new generations of fans. It was only in syndication throughout the following decade that the show’s lasting commercial and cultural impact would become apparent. The release of Star Trek: The Motion Picture in 1979, a decade after the original series’ cancellation, would kick-start a steady stream of Trek feature films and new TV and streaming series that has continued to this day.

Fans Grow Up To Be Astronauts

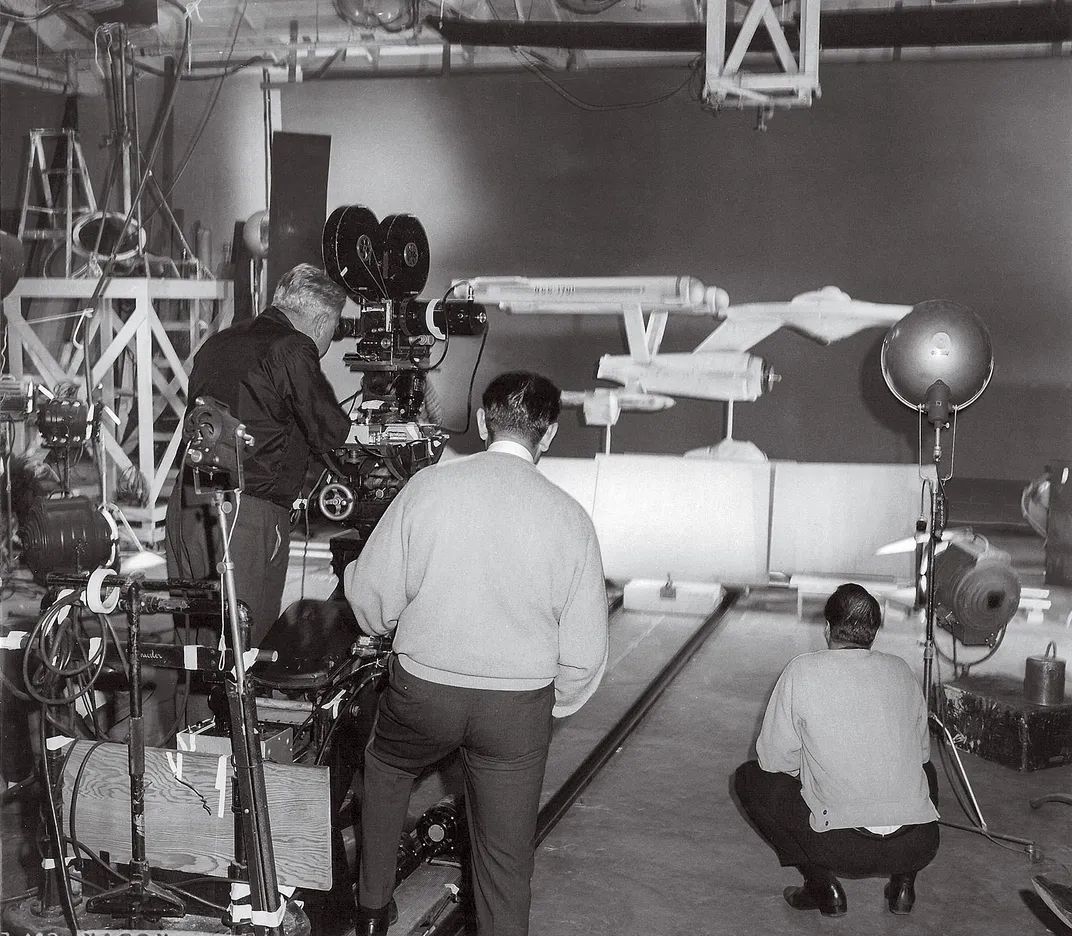

In the fall of 1974, the Smithsonian opened a new exhibit. “Life in the Universe” premiered in the old Arts & Industries Building before taking up permanent residence in the new National Air and Space Museum that opened on the National Mall two years later. Featured in the exhibit was the original 11-foot production model of the USS Enterprise used in the filming of the television series.

As Durant explained: “Our interest in acquiring Star Trek memorabilia relates to the study of the influence of science fiction upon future technological development. We believe that consideration of science fiction is relevant to current and future accomplishments in space.”

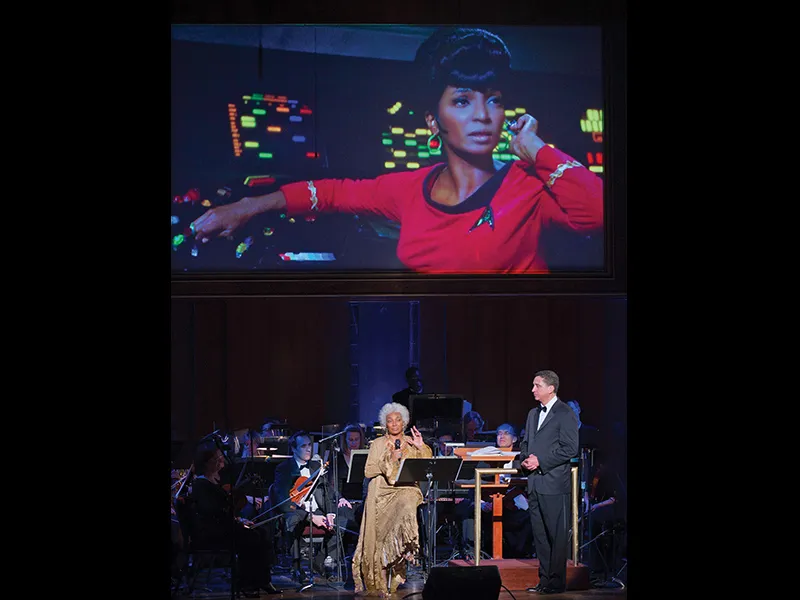

The approval of NASA, the aerospace community, and finally, the Smithsonian Institution lent Star Trek an unlikely cachet that has helped the franchise to—to borrow a phrase—live long and prosper. After other, higher-rated television shows of the same era were forgotten, Star Trek found new life. “We were kind of the NASA connection; the NASA fantasy and the show that NASA watched,” Nimoy recalled in The Star Trek Interview Book.

Credible and inspirational both, Star Trek became a favorite among subsequent generations of astronomers and spacefarers. In 2015, Italian astronaut Samantha Cristoforetti, who hadn’t even been born when Star Trek was canceled in 1969, tweeted a photo of herself wearing a Star Trek uniform in the cupola of the International Space Station. James B. Garvin, who became chief scientist at NASA Goddard decades after Nimoy’s 1967 visit and remains one of the top minds behind the agency’s Mars Exploration Program, grew up on Trek and made a point of watching the entire Star Trek: Voyager series one summer with his kids.

When the National Air and Space Museum celebrated its 40th anniversary in 2016, the newly restored Enterprise studio model—which for years had been kept on display in the basement level of the Museum’s gift shop—was moved to a more prominent location, in the Museum’s Milestones of Flight Hall near its Independence Avenue entrance. The “five-year mission” of inspiration it set out upon in 1966 remains, as of 2021, ongoing.

Glen E. Swanson is the former historian of the NASA Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas, and founder of Quest: The History of Spaceflight Quarterly. This is his first feature story for Air&Space.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/70/08/7008dc94-a1f1-4301-a827-2852c9b8c5db/06a_fm2021_roddenberrycrewe67-16643d_live.jpg)