14 Fun Facts About Fireworks

Number three: Fireworks are just chemical reactions

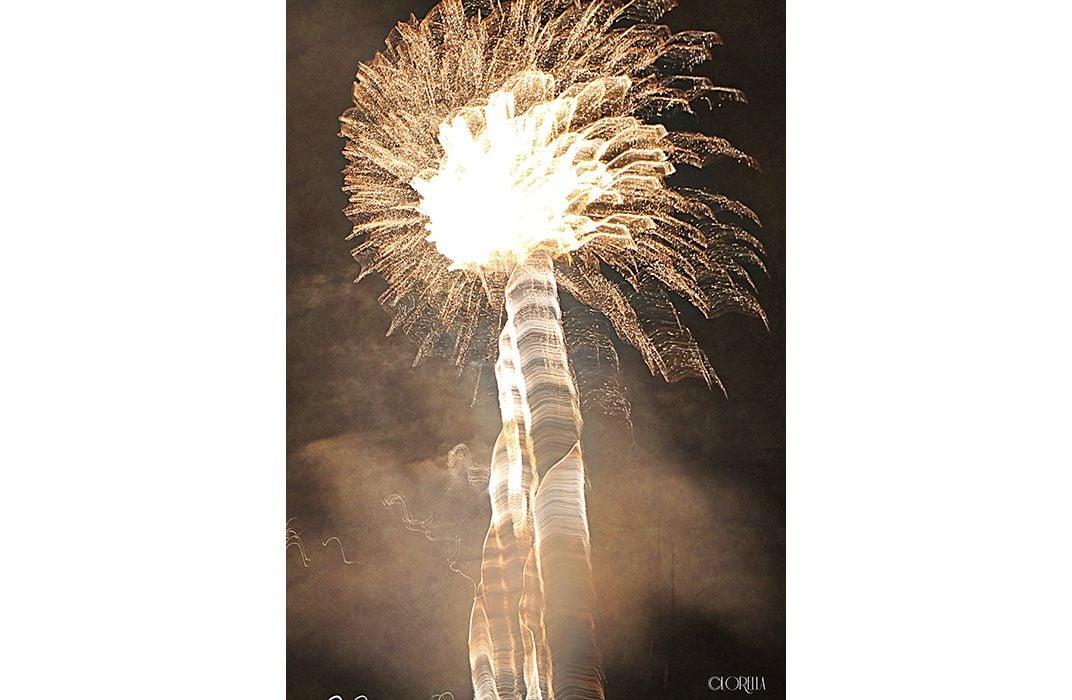

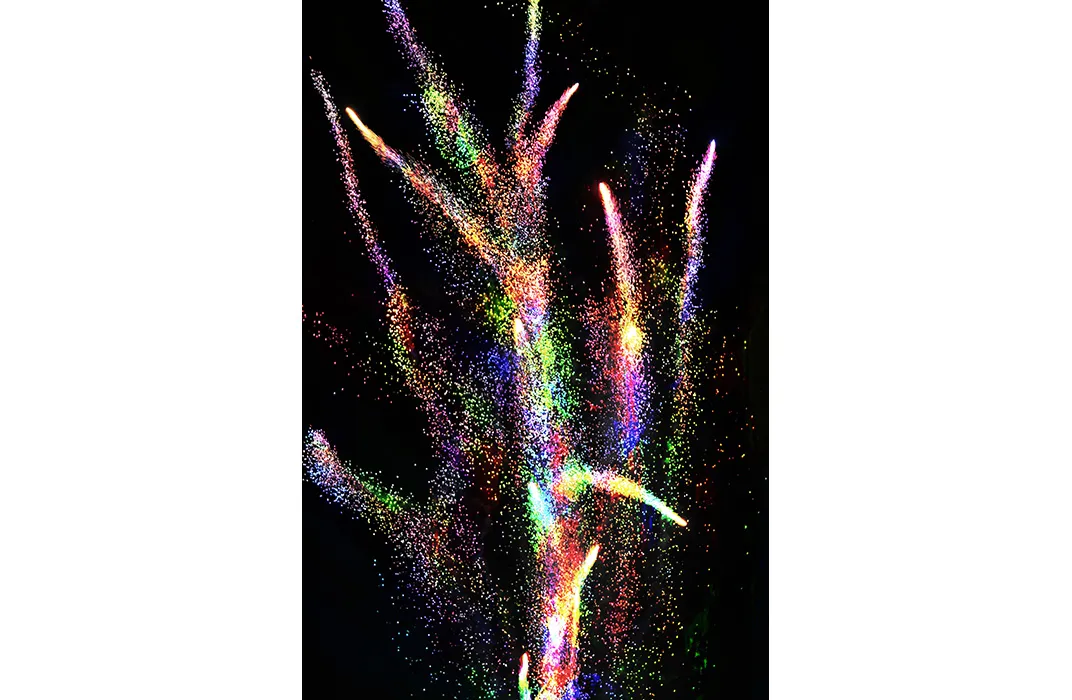

Like many Independence Days before it, this year’s celebrations will undoubtedly involve some sort of pyrotechnics display. Fireworks have been astounding audiences across the globe for centuries, and if the images above (all submitted by our readers) are any evidence, this year’s displays are sure to be just as spectacular as years past.

To pass the time in between rocket launches, here are 14 facts about the history and science of fireworks:

1. The Chinese used firecrackers to scare off mountain men.

As early as 200 B.C., the Chinese were writing on green bamboo stalks and heating it on coals to dry. Sometimes if left too long over the heat, the wood expanded and even burst, with a bang of course. According to Scientific American, Chinese scholars noticed that the noises effectively scared off abnormally large mountain men. And, thus, the firecracker was born. By some accounts, fireworks were also thought to scare away evil spirits.

2. The invention of fireworks led to the invention of pyrotechnic weaponry—not the other way around.

Sometime between 600 and 900 C.E., Chinese alchemists accidentally mixed saltpeter (or potassium nitrate) with sulfur and charcoal, inadvertently stumbling upon the crude chemical recipe for gunpowder. Supposedly, they had been searching for an elixir for immortality.

This “fire drug” (or huo yao) became an integral part of Chinese cultural celebrations. Stuffing the aforementioned bamboo tubes with gunpowder created a sort of sparkler. It wasn’t long before military engineers used the explosive chemical concoction to their advantage. The first recorded use of gunpowder weaponry in China dates to 1046 and references a crude gunpowder catapult. The Chinese also took traditional bamboo sparklers and attached them to arrows to rain down on their enemies. On a darker note, there are also accounts of fireworks being strapped to rats for use in medieval warfare.

3. Fireworks are just chemical reactions.

A firework requires three key components: an oxidizer, a fuel and a chemical mixture to produce the color. The oxidizer breaks the chemical bonds in the fuel, releasing all of the energy that’s stored in those bonds. To ignite this chemical reaction, all you need is a bit of fire, in the form of a fuse or a direct flame.

In the case of early fireworks, saltpeter was the oxidizing ingredient that drove the reaction, as British scholar Roger Bacon figured out in the early 1200s. Interestingly, Bacon kept his findings a secret, writing them in code to keep them out of the wrong hands.

4. Specific elements produce specific colors.

Firework color concoctions are comprised of different metal elements. When an element burns, its electrons get excited, and it releases energy in the form of light. Different chemicals burn at different wavelengths of light. Strontium and lithium compounds produce deep reds; copper produces blues; titanium and magnesium burn silver or white; calcium creates an orange color; sodium produces yellow pyrotechnics; and finally, barium burns green. Combining chlorine with barium or copper creates neon green and turquoise flames, respectively. Blue is apparently the most difficult to produce. Pyrotechnic stars comprised of these chemicals are typically propelled into the sky using an aerial shell.

5. China may have invented the firework, but Italy invented the aerial shell (and also made fireworks colorful).

Most modern fireworks displays use aerial shells, which resemble ice cream cones. Developed in the 1830s by Italian pyrotechnicians, the shells contain fuel in a cone bottom, while the “scoop” contains an outer layer of pyrotechnic stars, or tiny balls containing the chemicals needed to produce a desired color, and an inner bursting charge. Italians are also credited with figuring out that one could use metallic powders to create specific colors. Today, the shape that the firework produces is a product of the inner anatomy of the aerial shell or rocket.

6. Marco Polo probably wasn’t the first to bring gunpowder to Europe.

While Marco Polo did return from China in 1295 with fireworks, some argue that Europeans were likely exposed to gunpowder weaponry a little earlier during the Crusades. In the 9th century, China began trying to control the flow of gunpowder to its neighbors, in hopes of keeping the benefits of the technology to itself in case of conflict. Given that Arabs used various types of gunpowder-like weapons during the Crusades, gunpowder likely spread to the Middle East along the Silk Road in the intervening period, despite China’s best efforts.

7. Boom! Hiss! Crack! Some firework recipes include sound elements.

Layers of an organic salt, like sodium salicylate, combined with the oxidizer potassium perchlorate burn one at a time. As each layer burns, it slowly releases a gas, creating the whistling sound associated with most firework rockets. Aluminum or iron flakes can create hissing or sizzling sparkles, while titanium powder can create loud blasts, in addition to white sparks.

8. Fireworks are poisonous.

Given their ingredients, it makes sense that fireworks are not so great for the environment. Exploding a firework releases heavy metals, dioxins, perchlorates and other air pollutants into the atmosphere, and these pollutants have serious health effects in high doses. Barium nitrate can cause lung problems, while the oxidizer potassium perchlorate has been linked to thyroid problems and birth defects.

9. You can’t recycle fireworks.

Again, given their components, it’s probably not too surprising that recycling exploded fireworks isn’t an option. Before tossing them in the trash, soaking the discards in water is always a good idea. Any cardboard is likely too dirty to be of any value to recyclers, though it’s always a good idea to check with your city or municipality’s waste department. If you are trying to dispose of unused fireworks, it’s a good idea to call them as well, as most have special disposal procedures for explosives.

10. Don’t worry, chemists are developing more environmentally friendly firework recipes.

Some groups have already found substitutes for barium compounds and potassium perchlorate. By replacing chlorine with iodine, a team at the U.S. Army’s Pyrotechnics Technology and Prototyping Division found that sodium and potassium periodate are both safe and effective oxidizers. The same group also found success replacing barium with boron. The work is aimed at making more environmentally friendly flares for military use, but could also be applied to civilian fireworks. Some fireworks that use nitrogen-rich compounds in place of perchlorates have been used in small displays, but the challenge is making eco-friendly products as cheap as alternatives.

11. Americans have been setting off fireworks to celebrate their independence since 1777, at least.

Even some of the very first Independence Day celebrations involved fireworks. On July 4, 1777, Philadelphia put together an elaborate day of festivities, notes American University historian James R. Heintze. The celebration included a 13 cannon display, a parade, a fancy dinner, toasts, music, musket salutes, “loud huzzas,” and of course fireworks. Heintze cites this description from the Virginia Gazette on July 18, 1777:

“The evening was closed with the ringing of bells, and at night there was a grand exhibition of fireworks, which began and concluded with thirteen rockets on the commons, and the city was beautifully illuminated. Every thing was conducted with the greatest order and decorum, and the face of joy and gladness was universal. Thus may the 4th of July, that glorious and ever memorable day, be celebrated through America, by the sons of freedom, from age to age till time shall be no more.”

12. Fireworks aren’t for everybody.

Dogs whimper. Cats hide under the bed. Birds become so startled they get disoriented and fly into things. Even some people have extreme fears of fireworks or noise phobia.

13. Fireworks are dangerous (duh).

It might seem obvious, but it’s worth noting for those who plan to tinker with pyrotechnics in the backyard this 4th of July. Last year saw an uptick in fireworks-related injuries according to a new report by the Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC). In 2012, 8,700 people injured themselves using fireworks, and in 2013, that tally jumped to 11,300 people. Roughly 65 percent of those injuries happened in the 30 days surrounding July 4th. More than 40 percent of the injuries involved sparklers and rockets. In addition to injuries, fireworks can also spark wildfires.

14. Fireworks have been used in pranks for centuries.

After a series of fireworks shenanigans in 1731, officials in Rhode Island outlawed the use of fireworks for mischievous ends. At the turn of the 20th century, the Society for the Suppression of Unnecessary Noise campaigned against the use of fireworks (and other elements of urban hubbub), and their efforts are largely responsible for the first fireworks regulations in the United States.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2014-01-27_at_12.05.16_PM.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/af/bd/afbd1ba3-991a-40f1-ab8d-6991841c9adc/ashely_moore55037_6_275741.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2014-01-27_at_12.05.16_PM.png)