1934: The Art of the New Deal

An exhibition of Depression-era paintings by federally-funded artists provides a hopeful view of life during economic travails

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Baseball-at-Night-Morris-Kantor-631.jpg)

In early 1934, the United States was near the depths of what we hope will not go down in history as the First Great Depression. Unemployment was close to 25 percent and even the weather conspired to inflict misery: February was the coldest month on record in the Northeast. As the Federal Emergency Relief Act, a prototype of the New Deal work-relief programs, began to put a few dollars into the pockets of hungry workers, the question arose whether to include artists among the beneficiaries. It wasn't an obvious thing to do; by definition artists had no "jobs" to lose. But Harry Hopkins, whom President Franklin D. Roosevelt put in charge of work relief, settled the matter, saying, "Hell, they've got to eat just like other people!"

Thus was born the Public Works of Art Project (PWAP), which in roughly the first four months of 1934 hired 3,749 artists and produced 15,663 paintings, murals, prints, crafts and sculptures for government buildings around the country. The bureacracy may not have been watching too closely what the artists painted, but it certainly was counting how much and what they were paid: a total of $1,184,000, an average of $75.59 per artwork, pretty good value even then. The premise of the PWAP was that artists should be held to the same standards of production and public value as workers wielding shovels in the national parks. Artists were recruited through newspaper advertisements placed around the country; the whole program was up and running in a couple of weeks. People lined up in the cold outside government offices to apply, says George Gurney, deputy chief curator of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, where an exhibition of PWAP art is on display until January 3: "They had to prove they were professional artists, they had to pass a needs test, and then they were put into categories—Level One Artist, Level Two or Laborer—that determined their salaries."

It was not the PWAP but its better-known successor, the Works Progress Administration (WPA), that helped support the likes of young Mark Rothko and Jackson Pollock before they became luminaries. The PWAP's approach of advertising for artists might not have identified the most stellar candidates. Instead, "the show is full of names we scarcely recognize today," says Elizabeth Broun, the museum's director. The great majority of them were younger than 40 when they enrolled, by which time most artists have either made their reputation or switched to another line of work. Some, it appears, would be almost completely unknown today if the Smithsonian, in the 1960s, hadn't received the surviving PWAP artworks from government agencies that had displayed them. "They did their best work for the nation," Broun says, and then they disappeared below the national horizon to the realm of regional or local artist.

"The art they produced was rather conservative, and it wouldn't be looked at by most critics today," says Francis O'Connor, a New York City-based scholar and author of the 1969 book Federal Suppport for the Visual Arts. "But at the time it was a revelation to many people in America that the country even had artists in it."

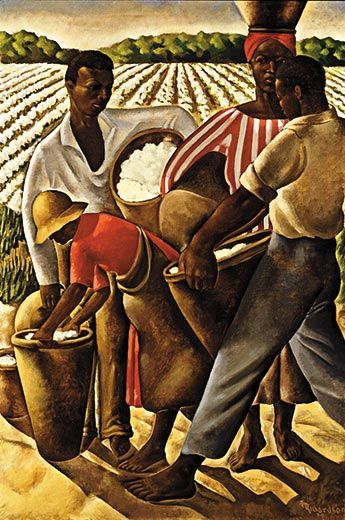

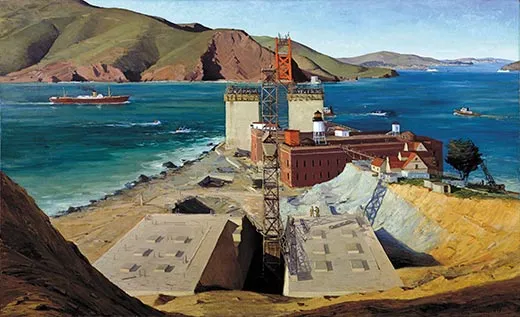

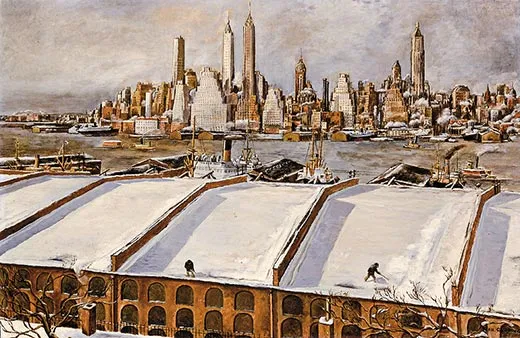

And not only artists, but things for them to paint. The only guidance the government offered about subject matter was that the "American scene" would be a suitable topic. The artists embraced that idea, turning out landscapes and cityscapes and industrial scenes by the yard: harbors and wharves, lumber mills and paper mills, gold mines, coal mines and open-pit iron mines, red against the gray Minnesota sky. Undoubtedly there would have been more farm scenes if the program had lasted into the summer. One of the few is Earle Richardson's Employment of Negroes in Agriculture, showing a stylized group of pickers in a field of what looks suspiciously like the cotton balls you buy in a drugstore. Richardson, an African-American who died the next year at just 23, lived in New York City, and his painting, it seems, could only have been made by someone who had never seen a cotton field.

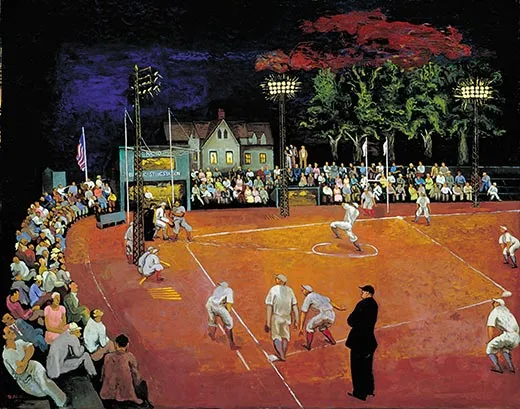

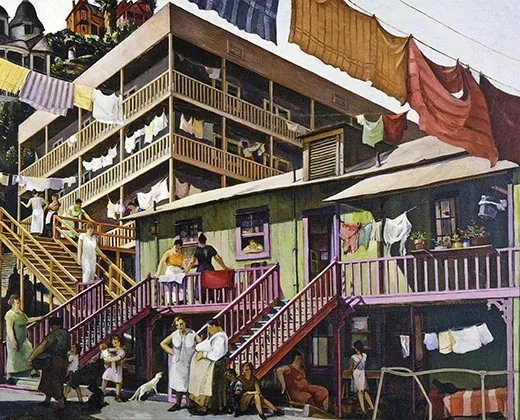

This is art, of course, not documentary; a painter paints what he sees or imagines, and the curators, Gurney and Ann Prentice Wagner, chose what interested them from among the Smithsonian's collection of some 180 PWAP paintings. But the exhibition also underscores a salient fact: when a quarter of the nation is unemployed, three-quarters have a job, and life for many of them went on as it had in the past. They just didn't have as much money. In Harry Gottlieb's Filling the Ice House, painted in upstate New York, men wielding pikes skid blocks of ice along wooden chutes. A town gathers to watch a game in Morris Kantor's Baseball at Night. A dance band plays in an East Harlem street while a religious procession marches solemnly past and vendors hawk pizzas in Daniel Celentano's Festival. Drying clothes flap in the breeze and women stand and chat in the Los Angeles slums in Tenement Flats by Millard Sheets; one of the better-known artists in the show, Sheets later created the giant mural of Christ on a Notre Dame library that is visible from the football stadium and nicknamed "Touchdown Jesus."

If there is a political subtext to these paintings, the viewer has to supply it. One can mentally juxtapose Jacob Getlar Smith's careworn Snow Shovellers—unemployed men trudging off to make a few cents clearing park paths—with the yachtsmen on Long Island Sound in Gerald Sargent Foster's Racing, but it's unlikely that Foster, described as "an avid yachtsman" on the gallery label, intended any kind of ironic commentary with his painting of rich men at play. As always, New Yorkers of every class except the destitute and the very wealthy sat side by side in the subway, the subject of a painting by Lily Furedi; the tuxedoed man dozing in his seat turns out, on closer inspection, to be a musician on his way to or from a job, while a young white woman across the aisle sneaks a glance at the newspaper held by the black man sitting next to her. None of this would seem unfamiliar today, except for the complete absence of litter or graffiti in the subway car, but one wonders how legislators from below the Mason-Dixon line might have felt about supporting a racially progressive artwork with taxpayers' money. They would be heard from a few years later, O'Connor says, after the WPA supported artists believed to be socialists, and subversive messages were detected routinely in WPA paintings: "They'd look at two blades of grass and see a hammer and sickle."

It is a coincidence that the show opened in the current delicate economic climate. It was planned in the summer of 2008 before the economy fell apart. Viewing it now, though, one can't help but feel the cold breath of financial ruin at one's back. There was a coziness in those glimpses of Depression-era America, a small-town feel even to the big-city streetscapes that can perhaps never be recaptured. The nation was still a setting for optimism 75 years ago, the factories and mines and mills awaiting the workers whose magic touch would awaken industries from their slumber. What abandoned subdivision, its streets choked with weeds, would convey the "American scene" to artists today?

Jerry Adler is a Newsweek contributing editor.