A Painter of Angels Became the Father of Camouflage

Turn-of-the-century artist Abbott Thayer created images of timeless beauty and a radical theory of concealing coloration

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Abbott-thayer-Peacock-in-the-Woods-388.jpg)

Down the full distance of my memory, a dauntingly stout box stood on its end in the barn of our Victorian house in Dublin, New Hampshire. In my morbid youthful imagination, maybe it was a child’s casket, maybe there was a skeleton inside. My father airily dismissed the contents: just the printing plates for the illustrations in a 1909 book, Concealing-Coloration in the Animal Kingdom, the brainchild of Abbott Handerson.

Thayer, a major turn-of-the-century painter who died in 1921. He was a mentor to my artist father (whose name I bear) and a family icon. He was the reason my father stayed in Dublin: to be near the man he revered.

I was recently visited in Dublin by Susan Hobbs, an art historian researching Thayer. This was the moment to open the box—which now felt to me like an Egyptian sarcophagus, filled with unimagined treasures. And indeed it was! The plates for the book were there—and with them, cutouts of blossoms and butterflies, birds and bushes—lovely vignettes to show how coloration can conceal objects by merging them with their backgrounds. Everything was wrapped in a 1937 Sunday Boston Globe and New York Herald Tribune.

Also, I held in my hands a startling artifact of military history. Green and brown underbrush was painted on a series of horizontal wooden panels. A string of paper-doll soldiers dappled green and brown could be superimposed on the landscapes to demonstrate how camouflage-design uniforms would blend into the backgrounds. Cutouts and stencils in the shape of soldiers, some hanging from strings, could be placed on the panels as well, to demonstrate degrees of concealment. Here was Abbott Thayer, the father of camouflage.

Nowadays camouflage togs are worn as fashion statements by trendy clotheshorses, and as announcements of machismo by both men and women. The “camo” pattern is the warrior wardrobe for rebels and rogues of all stripes, and hunters of the birds and animals Thayer studied to the point of near worship. Catalogues and stylish boutiques are devoted to camouflage chic. There are camo duffels, camo vests, even camo bikinis.

This evolution is heavily ironic. A strange and astonishing man, Thayer had consecrated his life to painting “pictures of the highest human soul beauty.” He was one of a small group who returned from Paris art schools in the late 1800s with a new vision of American art. They were painters of atmosphere, apostles of timeless beauty, often embodied by depictions of idealized young women. Distinct from the storytelling pre-Raphaelites, the American Impressionists and such muscular Realists as Winslow Homer and Thomas Eakins, the group included Thomas Dewing, Dwight Tryon, George de Forest Brush, the sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens, and James McNeill Whistler, who remained abroad. Deemed a “rare genius” by the railroad car magnate Charles Lang Freer, his patron and mentor, Thayer in that era was considered one of the finest figure painters in America.

Thayer’s second obsession was nature. An Emersonian transcendentalist, he found in nature an unsullied form of the purity, the spiritual truth and the beauty he sought in his painting. This combination of art and naturalism led him to his then-radical theory of concealing coloration—how animals hide from their predators, and prey. The foundation of military camouflage, it would have been formulated without Thayer and his particular contributions. Types of camouflage had long existed. Brush was used to conceal the marching soldiers in Shakespeare’s Macbeth, and the headdresses and war paint worn by African warriors, to cite Thayer’s own example, served to disrupt their silhouettes. But it was Thayer who, in the early 1890s, began creating a wholly formed doctrine of concealing coloration, worked out through observation and experiment.

The theory emerged from the total mingling of his art and his nature studies. Thayer once explained to William James, Jr.—son of the famed philosopher and a devoted disciple of Thayer’s—that concealing coloration was his “second child.” This child, said Thayer, “has hold of one of my hands and my painting has hold of the other. When little C.C. hangs back, I can not go forward....He is my color-study. In birds’ costumes I am doing all my perceiving about the color I now get into my canvases.”

Thayer believed that only an artist could have originated this theory. “The whole basis of picture making,” he said, “consists in contrasting against its background every object in the picture.” He also was a preeminent technician in paint, the acknowledged American master of the color theories developed in Munich and Paris—theories of hue and chroma, of color values and intensities, of how colors enhance or cancel one another when juxtaposed.

Thayer based his concept on his perceptions of the ways in which nature “obliterates” contrast. One is by blending. The colorations of birds, mammals, insects and reptiles, he said, mimic the creatures’ environments. The second is by disruption. Strong arbitrary patterns of color flatten contours and break up outlines, so denizens either disappear or look to be something other than what they are.

Contours are further confused, Thayer maintained, by the flattening effect of what he termed “countershading”: the upper areas of animals tend to be darker than their shadowed undersides. Thus the overall tone is equalized. “Animals are painted by Nature darkest on those parts which tend to be most lighted by the sky’s light, and vice versa,” wrote Thayer. “The result is that their gradation of light-and-shade, by which opaque solid objects manifest themselves to the eye, is effaced at every point, and the spectator seems to see right through the space really occupied by an opaque animal.”

To demonstrate the effects of countershading, he made small painted birds. One rainy day in 1896 he led Frank Chapman, a curator at the American Museum of Natural History in New York, to a construction site. At a distance of 20 feet, he asked how many model birds Chapman saw in the mud. “Two,” Chapman said. They advanced closer. Still two. Standing practically on top of the models, Chapman discovered four. The first two were entirely earth brown. The “invisible” two were countershaded, with their upper halves painted brown and their lower halves painted pure white.

Thayer held demonstrations of his theory throughout the East. But while many prominent zoologists were receptive to his ideas, numerous other scientists acrimoniously attacked him. They argued correctly that conspicuous coloring was also designed to warn off a predator or attract a perspective mate. In particular, they resented Thayer’s insistence that his theory be accepted all or nothing—like Holy Scripture.

His most famous detractor was big-game-hunting Teddy Roosevelt, who publicly scoffed at Thayer’s thesis that the blue jay is colored so as to disappear against the blue shadows of winter snows. What about summer? Roosevelt asked. From his own experience, he knew that zebras and giraffes were clearly visible in the veld from miles away. “If you...sincerely desire to get at the truth,” wrote Roosevelt in a letter, “you would realize that your position is literally nonsensical.” Thayer’s law of obliterative countershading did not recieve official acceptance until 1940, when a prominent British naturalist, Hugh B. Cott, published Adaptive Coloration in Animals.

Although concealing coloration, countershading and camouflage are now axiomatically understood, at the end of the 19th century it probably took an eccentric fanatic like Thayer—a freethinker antagonistic to all conventions, a man eminent in a separate field—to break with the rigid mind-set of the naturalist establishment.

Born in 1849, Thayer grew up in Keene, New Hampshire. At age 6, the future artist was already “bird crazy,” as he put it—already collecting skins. Attending a prep school in Boston, he studied with an animal painter and had begun selling paintings of birds and animals when at 19 he arrived at the National Academy of Design in New York.

There Thayer met his feminine ideal, an innocent soul—poetic, graceful, fond of philosophic reading and discussion. Her name was Kate Bloede. They were married in 1875, and at age 26, Thayer put aside his naturalist self and sailed for Paris to begin four years of study at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts under Jean-Léon Gérôme, a great master of composition and the human figure.

When they returned to America, Thayer supported his family by doing commissioned portraits. By 1886 he and Kate had three children, Mary, Gladys and Gerald. Brilliant, isolated, ascetic, hyperintense, an almost pure example of late-19th-century romantic idealism, Thayer epitomized the popular image of a genius. His mind would race at full throttle in a rush of philosophies and certainties. His joy was exploring the imponderables of life, and he scrawled passionate, barely readable letters, his second thoughts routinely continued in a series of postscripts.

Impractical, erratic, improvident, Thayer described himself as “a jumper from extreme to extreme.” He confessed to his father that his brain only “takes care of itself for my main function, painting.” Later he would compose letters to Freer in his head and then be surprised that his patron had not actually received them. Though Thayer earned a fortune, selling paintings for as much as $10,000, an enormous sum in those days, money was often a problem. With wheedling charm he would pester Freer for loans and advance payments.

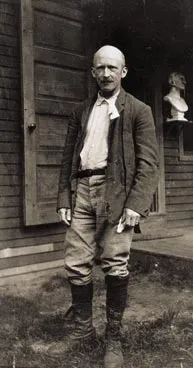

Thayer cut a singular figure. A smallish man, 5 feet 7 inches tall, lean and muscular, he moved with a quick vitality. His narrow, bony face, with its mustache and aquiline nose, was topped by a broad forehead permanently furrowed by frown lines from concentration. He began the winter in long woolen underwear, and as the weather warmed, he gradually cut off the legs till by summer he had shorts. Winter and summer he wore knickers, knee-high leather boots and a paint-splotched Norfolk jacket.

After moving the family from place to place, in 1901 Thayer settled permanently, 13 miles from Keene, in Dublin, New Hampshire, just below the great granite bowl of Mount Monadnock. His Thoreauesque communion with nature permeated the entire household. Wild animals—owls, rabbits, woodchucks, weasels—roamed the house at will. There were pet prairie dogs named Napoleon and Josephine, a red, blue and yellow macaw, and spider monkeys that regularly escaped from their cages. In the living room stood a stuffed peacock, probably used as a model for a painting (opposite) in the protective coloration book. A stuffed downy woodpecker, which in certain lights disappeared into its artfully arranged background of black winter twigs and branches, held court in the little library.

Promoting to ornithologists his theory of protective coloration, Thayer met a young man who immediately was adopted as an honorary son. His name was Louis Agassiz Fuertes, and though he would become a famous painter of birds, he began as an affectionate disciple.

Both men were fascinated with birds. They regularly exchanged skins and Fuertes joined Thayer on birding expeditions. He spent a summer and two winters with the family, joining in their high intellectual and spiritual arguments—the exact interpretation of the Icelandic Sagas—and their rushes to the dictionary or relief globe to settle questions of etymology and geography. On regular walks in the woods, Fuertes summoned birds by whistling their calls—like Thayer, who stood on the summit of Mount Monadnock in the twilight and attracted great horned owls by making a sucking sound on the back of his hand. One owl, it is said, perched on top of his bald head.

Fuertes also served as a tutor to Gerald. Thayer’s children were not sent to school. He needed their daily companionship, he said, and feared the germs they might pick up. He thought the purity of their youth would be corrupted by a confining, formal education. The children were well taught at home, not the least by Thayer’s lofty environment of music and books. Mary grew up to be an expert linguist. Gladys became a gifted painter and a fine writer. Gerald, also an artist, was to be the author of record of Concealing-Coloration in the Animal Kingdom.

The Dublin house had been given to the Thayer family by Mary Amory Greene. A direct descendent of the painter John Singleton Copley, Greene had been one of Thayer’s students. She made herself Thayer’s helper, handling correspondence, collecting fees—and writing substantial checks. She was one of several genteel, affluent, single females delighted to dedicate themselves to the artist. He once explained, “A creative genius uses all his companions...passing to each some rope or something to handle at his fire, i.e. his painting or his poem.”

Another savior was Miss Emmeline “Emma” Beach. A tiny sprite of a woman with reddish-gold hair, she was gentle, understanding, selfless, but also efficient, effectual, and moneyed. Her father owned the New York Sun. Kate was as disorganized as her husband, so both embraced Emma’s friendship. She cheerfully became the Thayer family factotum, struggling to bring order to the chaos.

In 1888 Kate’s mind folded into melancholia and she entered a sanatorium. Alone with the three children, blaming himself for causing Kate’s “dark state,” Thayer turned more and more to Emma. He wrote her wooing, confiding letters, calling her his “Dear fairy godmother” and imploring her to come for extended visits. When Kate died of a lung infection in 1891 in the sanatorium, Thayer proposed to Emma by mail, including the plea that Kate had wished her to care for the children. They were married four months after Kate’s death, and it was with Emma that Thayer settled year-round in Dublin. Now it fell to her to keep the fragile artist glued together.

This was a considerable challenge. His life was blighted by what he called “the Abbott pendulum.” There were highs of blissful “all-wellity” when he reveled in “such tranquility, such purity of nature and such dreams of painting.” At these times he was his essential self—a man of ingratiating charm and grace and generosity. But then depressions set in. “My sight turns inward,” he wrote, “and I have such a state of sick disgust at myself....”

He suffered from “oceans of hypochondria,” which he blamed on his mother, and from an “irritability” he claimed to inherit from his father. Harassed by sleeplessness, exhaustion and anxiety, by petty illnesses, bad eyes and headaches, he kept his state of health, excellent or terrible, constantly in the foreground.

He was convinced that fresh mountain air was the best medicine for everyone, and the entire family slept under bearskin rugs in outdoor lean-tos—even in 30-below weather. In the main house, windows were kept open winter and summer. The place had never been winterized, and what heat there was came from fireplaces and small wood-burning stoves. Illumination was provided by kerosene lamps and candles. Until a water tower fed by a windmill was built, the only plumbing was a hand pump in the kitchen. A privy stood behind the house. But there was always the luxury of a cook and house maids, one of whom, Bessie Price, Thayer used as a model.

In 1887 Thayer found the leitmotif for his most important painting. Defining art as “a no-man’s land of immortal beauty where every step leads to God,” the forefather of today’s raucous camouflage painted his 11-year-old daughter Mary as the personification of virginal, spiritual beauty, giving her a pair of wings and calling the canvas Angel. This was the first in a gallery of chaste, lovely young women, usually winged, but human nevertheless. Although Thayer sometimes added halos, these were not paintings of angels. The wings, he said, were only there to create “an exalted atmosphere”—to make the maidens timeless.

For Thayer, formal religion smacked of “hypocrisy and narrowness.” His God was pantheistic. Mount Monadnock, his field station for nature studies, was “a natural cloister.” He painted more than a dozen versions of it, all with a sense of looming mystery and “wild grandeur.”

Believing that his paintings were the “dictation of a higher power,” he tended to paint in bursts of “God given” creative energy. His personal standards were impossibly high. Driven by his admitted vice of “doing them better and better,” he was doomed always to fall short. Finishing a picture became horrendously hard. He was even known to go to the railroad station at night, uncrate a painting destined for a client and work on it by lantern light.

Such fussing sometimes ruined months or even years of work. In the early 1900s he began preserving “any achieved beauty” by retaining young art students—including my father—to make copies of his effects. Two, three and four versions of a work might be under way. Thayer compulsively experimented on all of them, finally assembling the virtues of each onto one canvas.

Though well aware of his quirks and weaknesses, young painters like my father and Fuertes revered Thayer almost as a flawed god. William James, Jr., described standing in Thayer’s studio before the winged Stevenson Memorial. “I felt myself to be, somehow, ‘in the presence.’ Here was an activity, an accomplishment, which my own world...had never touched. This could be done—was being done that very morning by this friendly little man with the distant gaze. This was his world where he lived and moved, and it seemed to me perhaps the best world I had ever met.”

The inspirational spell cast by Thayer also was experienced by a noted artist named William L. Lathrop. In 1906 Lathrop visited a show at the Academy of Fine Arts in Philadelphia. He wrote: “A big portrait by Sargent. Two portrait heads by Abbott Thayer. The Sargent is a wonderfully brilliant performance. But one finds a greater earnestness in the Thayers. That his heart ached with love for the thing as he painted, and your own heart straight away aches with love for the lover. You know that he strove and felt himself to have failed and you love him the more for the failure.”

While “the boys” copied the morning’s work, Thayer spent afternoons finding in nature a relief from his fervid preoccupations. He climbed Mount Monadnock, canoed and fly-fished on nearby Dublin Pond. To him each bird and animal was exquisite. He and his son, Gerald, collected bird skins in the Eastern United States, and as far afield as Norway, Trinidad and South America. By 1905 they had amassed a trove of 1,500 skins. Using a needle, Thayer would lift each feather into its proper position with infinite delicacy. “I gloat and gloat,” he once wrote. “What design!”

World War I devastated the 19th-century spirit of optimism that helped sustain Thayer’s idealism. The possibility of a German victory drew Thayer out of seclusion and spurred him to promote the application of his theories of protective coloration to military camouflage. The French made use of his book in their efforts, adapting his theories to the painting of trains, railroad stations, and even horses, with “disruptive” patterns. The word “camouflage” probably comes from the French camouflet, the term for a small exploding mine that throws up gas and smoke to conceal troop movement. The Germans, too, studied Thayer’s book to help them develop techniques for concealing their warships.

When the British were less enthusiastic, Thayer’s obsessiveness went into overdrive. He virtually stopped painting and began an extended campaign to persuade Britain to adopt his ideas, both on land and sea. In 1915 he enlisted the help of the great expatriate American painter John Singer Sargent, whose fame enabled him to arrange a meeting at the British War Office for Thayer. Traveling alone to England, Thayer failed to go to the War Office. Instead he toured Britain in a state of nervous overexcitement, giving camouflage demonstrations to friendly naturalists in Liverpool and Edinburgh in the hopes of mobilizing their support. This detour, it turns out, was largely a ploy to postpone what was always for him a paralyzing fear: facing an unsympathetic audience.

Finally Thayer arrived in London for the appointment. He was exhausted, confused and erratic. At one point, he found himself walking a London street with tears streaming down his face. Immediately he boarded the next ship for America, leaving behind at his hotel a package that Sargent took to the War Office.

I always loved hearing my father tell what happened then. In the presence of the busy, skeptical generals, Sargent opened the package. Out fell Thayer’s paint-daubed Norfolk jacket. Pinned across it were scraps of fabric and several of Emma’s stockings. To Thayer, it told the entire story of disruptive patterning. To the elegant Sargent, it was an obscenity—“a bundle of rags!” he fumed to William James, Jr. “I wouldn’t have touched it with my stick!”

Later Thayer received word that his trip had born some sort of fruit: “Our British soldiers are protected by coats of motley hue and stripes of paint as you suggested,” wrote the wife of the British ambassador to the United States. Thayer continued battling to make the British Navy camouflage its ships. In 1916, overstressed and unstrung, he broke down, and in Emma’s words was “sent away from home for a rest.”

The United States entered the war in April 1917, and when a number of artists proposed their own ways to camouflage U.S. warships, Thayer refocused his frenzy. He sent a copy of the concealing coloration book to Franklin Delano Roosevelt, then Assistant Secretary of the Navy, and bombarded him with passionate letters decrying the wrongheaded perversion of his ideas by others. “It will be disastrous if, after all, they dabble in my discoveries,” he wrote. “I beg you, be wise enough as to try accurately, mine, first.”

White, he contended, was the best concealing color for blending with the horizon sky. Dark superstructures, like smokestacks, could be hidden by white canvas screens or a bright wire net. White would be the invisible color at night. One proof, he insisted, was the white iceburg struck by the Titanic. Although some credence would later be given to this theory in a 1963 Navy manual on ship camouflage, Thayer’s ideas in this regard were primarily inspirational rather than practical.

His theories had a more direct effect on Allied uniforms and matériel. A Camouflage Corps was assembled—an unmilitary lot led by sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens’ son, Homer. It was for his edification that Thayer had prepared the camouflage demonstration panels that I discovered in Dublin. By 1918 this motley corps contained 285 soldiers—carpenters, iron workers, sign painters. Its 16 officers included sculptors, scenery designers, architects and artists. One was my father, a second lieutenant.

In France a factory applied disruptive, variegated designs to American trucks, sniper suits and observation posts, thereby, as an Army report explained, “destroying identity by breaking up the form of the object.” “Dazzle” camouflage used pieces of material knotted to wire netting, casting shadows that broke up the shapes beneath.

During 1918, Thayer’s frustration over ship camouflage and terror over the war reached a continual, low-grade hysteria. It was too much even for Emma. That winter she fled to her sister in Peekskill, New York. Thayer took refuge in a hotel in Boston, then took himself to a sanatorium. From there he wrote Emma, “I lacked you to jeer me out of suicide and I got into a panic.”

In early 1919 they were together again. But by March, Emma needed another rest in Peekskill, and again during the winter of 1920-21. Despite her absences, Thayer settled down, cared for by his daughter Gladys and his devoted assistants. Late that winter he began a picture that combined his two most cherished themes: an “angel” posed open-armed in front of Mount Monadnock (left). In May he had a series of strokes. The last one, on May 29, 1921, killed him. On hearing of Thayer’s death, John Singer Sargent said, “Too bad he’s gone. He was the best of them.”

The Thayer cosmos disintegrated, drifting away into indifference and neglect. There was a memorial exhibition at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art within a year, but for decades many of his finest works remained unseen, stored in the vaults of the Smithsonian’s Freer Gallery of Art, which is prohibited from lending paintings for outside exhibitions. In the post-Armory Show era the changing fashions of the art world regarded Thayer’s angels as sentimental relics of a defunct taste.

Emma died in 1924. For a time the little Dublin complex stood empty, decaying year after year. When I was 9, my brother and I climbed up on the roof of Gerald’s house, near Thayer’s studio, and entered the attic through an open hatch. In one corner, heaped up like a hay mow, was a pile of Gerald’s bird skins. I touched it. Whrrrr! A raging cloud of moths. The horror was indelible. Thayer’s own prized collection of skins was packed in trunks and stored in an old mill house on the adjacent property. Ultimately, the birds deteriorated and were thrown out. In 1936 Thayer’s house and studio were torn down. Gerald’s house lasted only a year or so longer. The box in our barn was apparently given to my father for safekeeping.

Today, at the end of the 20th century, angels are very much in vogue. Thayer’s Angel appeared on the cover of the December 27, 1993, issue of Time magazine, linked to an article titled “Angels Among Us.” These days angels are appearing in films, on TV, in books and on the Web. Today, too, art historians are looking receptively at the end of the 19th century. A major Thayer exhibition opens on April 23 at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American Art. Curated by Richard Murray, the show—which marks the 150th anniversary of the artist’s birth—will run through September 6. In addition, the Freer Gallery will mount a small exhibit of Thayer’s winged figures starting June 5.

In 1991, during the Gulf War, I watched Gen. Norman Schwarzkopf hold televised press conferences in full camouflage regalia. Yes, Thayer did finally make his point with the military. But he sacrificed his health—and perhaps even his life—promoting what, in some respects, has now become a pop fad that announces rather than hides. Virtually no one knows that all that raiment is the enduring legacy of a worshiper of virginal purity and spiritual nobility. This probably delights Abbott Thayer.

Freelance writer Richard Meryman’s most recent book is Andrew Wyeth, A Secret Life, published by HarperCollins.