A WWII Propaganda Campaign Popularized the Myth That Carrots Help You See in the Dark

How a ruse to keep German pilots confused gave the Vitamin-A-rich vegetable too much credit

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Food-Think-WWII-carrots-631.png)

The science is pretty sound that carrots, by virtue of their heavy dose of Vitamin A (in the form of beta carotene), are good for your eye health. A 1998 Johns Hopkins study, as reported by the New York Times, even found that supplemental pills could reverse poor vision among those with a Vitamin A deficiency. But as John Stolarczyk knows all too well as curator of the World Carrot Museum, the truth has been stretched into a pervasive myth that carrots hold within a super-vegetable power: improving your night-time vision. But carrots cannot help you see better in the dark any more than eating blueberries will turn you blue.

“Somewhere on the journey the message that carrots are good for your eyes became disfigured into improving eyesight,” Stolarczyk says. His virtual museum, 125 pages full of surprising and obscure facts about carrots, investigates how the myth became so popular: British propaganda from World War II.

Stolarczyk is not confident about the exact origin of the faulty carrot theory, but believes that it was reinforced and popularized by the Ministry of Information, an offshoot of a subterfuge campaign to hide a technology critical to an Allied victory.

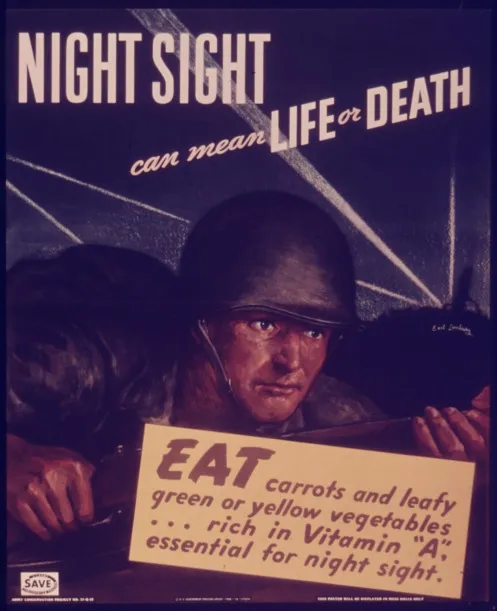

During the 1940 Blitzkrieg, the Luftwaffe often struck under the cover of darkness. In order to make it more difficult for the German planes to hit targets, the British government issued citywide blackouts. The Royal Air Force were able to repel the German fighters in part because of the development of a new, secret radar technology. The on-board Airborne Interception Radar (AI), first used by the RAF in 1939, had the ability to pinpoint enemy bombers before they reached the English Channel. But to keep that under wraps, according to Stolarczyk’s research pulled from the files of the Imperial War Museum, the Mass Observation Archive, and the UK National Archives, the Ministry provided another reason for their success: carrots.

In 1940, RAF night fighter ace, John Cunningham, nicknamed “Cat’s Eyes”, was the first to shoot down an enemy plane using AI. He’d later rack up an impressive total of 20 kills—19 of which were at night. According to “Now I Know” writer Dan Lewis, also a Smithsonian.com contributor, the Ministry told newspapers that the reason for their success was because pilots like Cunningham ate an excess of carrots.

The ruse, meant to send German tacticians on a wild goose chase, may or may not have fooled them as planned, says Stolarczyk.

“I have no evidence they fell for it, other than that the use of carrots to help with eye health was well ingrained in the German psyche. It was believed that they had to fall for some of it,” Stolarczyk wrote in an email as he reviewed Ministry files for his upcoming book, tentatively titled How Carrots Helped Win World War II. “There are apocryphal tales that the Germans started feeding their own pilots carrots, as they thought there was some truth in it.”

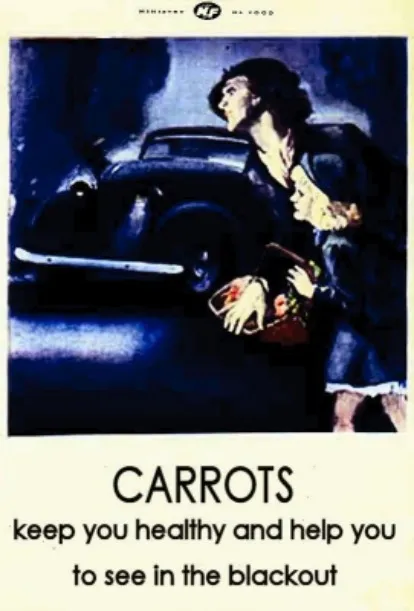

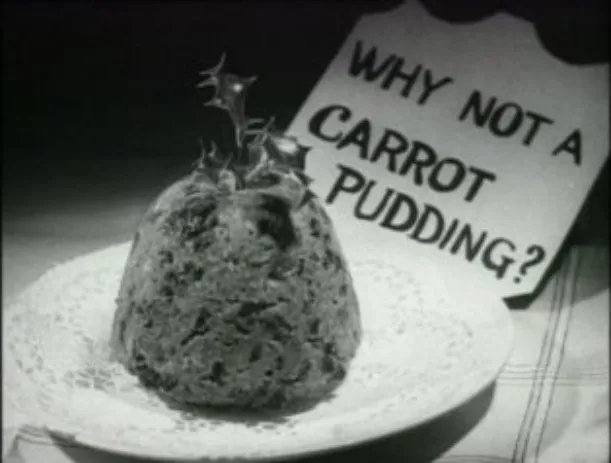

Whether or not the Germans bought it, the British public generally believed that eating carrots would help them see better during the citywide blackouts. Advertisements with the slogan “Carrots keep you healthy and help you see in the blackout” (like the one pictured below) appeared everywhere.

But the carrot craze didn’t stop there—according to the Food Ministry, when a German blockade of food supply ships made many resources such as sugar, bacon and butter unavailable, the war could be won on the “Kitchen Front” if people changed what they ate and how they prepared it. In 1941, Lord Woolton, the Minister of Food, emphasized the call for self-sustainability in the garden:

“This is a food war. Every extra row of vegetables in allotments saves shipping. The battle on the kitchen front cannot be won without help from the kitchen garden. Isn’t an hour in the garden better than an hour in the queue?”

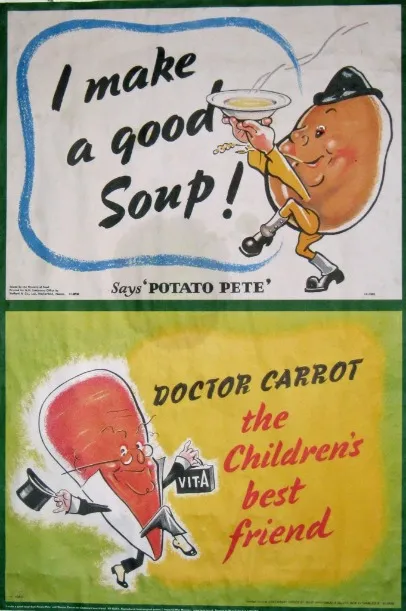

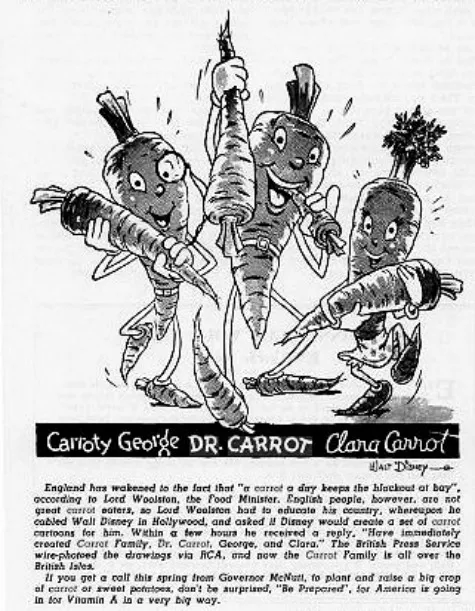

That same year, the British Ministry of Food launched a Dig For Victory Campaign which introduced the cartoons ”Dr. Carrot” and “Potato Pete”, to get people to eat more of the vegetables (bread and vegetables were never on the ration during the war). Advertisements encouraged families to start “Victory Gardens” and to try new recipes using surplus foods as substitutes for those less available. Carrots were promoted as a sweetener in desserts in the absence of sugar, which was rationed to eight ounces per adult per week. The Ministry’s “War Cookery Leaflet 4″ was filled with recipes for carrot pudding, carrot cake, carrot marmalade and carrot flan. Concoctions like “Carrolade” made from rutabagas and carrots emerged from other similar sources.

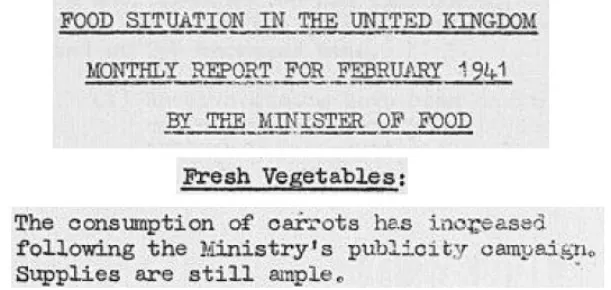

Citizens regularly tuned into radio broadcasts like “The Kitchen Front“, a daily, five-minute BBC program that doled out hints and tips for new recipes. According to Stolarczyk, the Ministry of Food encouraged so much extra production of the vegetable that by 1942, it was looking at 100,000 ton surplus of carrots.

Stolarczyk has tried many of the recipes including Woolton Pie (named for Lord Woolton), Carrot Flan and Carrot Fudge. Carrolade, he says, was one of the stranger ideas.

“The Ministry of Food had what I call a ‘silly ideas’ section where they threw out crazy ideas to see what would stick—this was one of those,” he says. “At the end of the day, the people were not stupid. If it tasted horrible, they tended to shy away.”

Dr. Carrot was everywhere—radio shows, posters, even Disney helped out. Hank Porter, a leading Disney cartoonist designed a whole family based on the idea of Dr. Carrot—Carroty George, Pop Carrot and Clara Carrot—for the British to promote to the public.

Dr. Carrot and Carroty George had some competition in the U.S., however—from wise-guy carrot-chomping Bugs Bunny, born around the same time. While Bugs served his own role in U.S. WWII propaganda cartoons, the connection between his tagline, “What’s up Doc?,” and the UK’s “Dr. Carrot” is probably just a coincidence.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/561436_10152738164035607_251004960_n.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/561436_10152738164035607_251004960_n.jpg)