Americans in Paris

In the late 19th century, the City of Light beckoned Whistler, Sargent, Cassatt and other young artists. What they experienced would transform American art

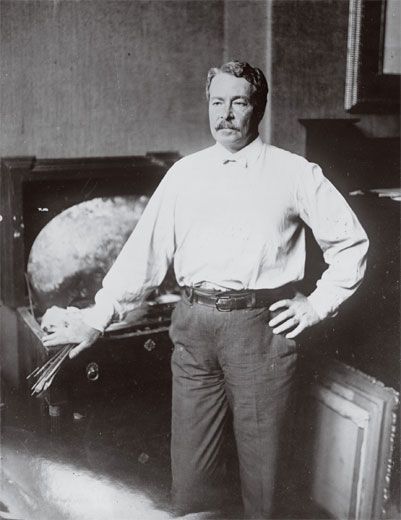

Her skin powdered lavender-white and her ears provocatively rouged, Virginie Avegno Gautreau, a Louisiana native who married a prosperous French banker, titillated Parisian society. People talked as much of her reputed love affairs as of her exotic beauty. In late 1882, determined to capture Madame Gautreau's distinctive image, the young American painter John Singer Sargent pursued her like a trophy hunter. At first she resisted his importunings to sit for a portrait, but in early 1883, she acquiesced. During that year, at her home in Paris and in her country house in Brittany, Sargent painted Gautreau in sessions that she would peremptorily cut short. He had had enough free time between sittings that he had taken on another portrait—this one commissioned—of Daisy White, the wife of an American diplomat about to be posted to London. Sargent hoped to display the two pictures—the sophisticated Gautreau in a low-cut black evening dress and the proper, more matronly White in a frilly cream-and-white gown—in 1883 at the Paris Salon, the most prestigious art show in the city. Instead, because of delays, the finished paintings would not be exhibited until the following year at, respectively, the Paris Salon and the Royal Academy in London. Seeing them together as Sargent intended is one of the pleasures of "Americans in Paris, 1860-1900," now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City (after earlier stops at the National Gallery of London and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston) through January 28, 2007.

The two portraits point like opposing signposts to the roads that Sargent might choose to travel. The Gautreau hearkens back to the 17th-century Spanish master Velázquez, whose radically pared-down, full-length portraits in a restricted palette of blacks, grays and browns inspired Édouard Manet and many modern painters. The White recalls the pastel-colored depictions by 18th-century English society painters such as Sir Joshua Reynolds, Thomas Gainsborough and George Romney.

Gautreau's upthrust chin and powdered flesh, with a strap of her gown suggestively fallen from her shoulder, caused a scandal; both painter and sitter were vilified as "detestable" and "monstrous." One critic wrote that the portrait was "offensive in its insolent ugliness and defiance of every rule of art." At Sargent's studio on the night of the Salon opening, Gautreau's mother complained to the artist that "all Paris is making fun of my daughter. She is ruined." He resolutely denied her plea to have the picture removed. But after the exhibition closed, he repainted the dropped strap, putting it back into its proper place. He kept the painting in his personal collection, and when he finally sold it to the Metropolitan Museum in 1916, he asked that it be identified only as a portrait of "Madame X." It is "the best thing I have done," he wrote at the time.

The outraged response to the Gautreau portrait helped push Sargent toward the safer shores of society portraiture. He was more interested in pleasing than in challenging his public. That may be what novelist Henry James had in mind when he wrote to a friend in 1888 that he had "always thought Sargent a great painter. He would be greater still if he had one or two things he isn't—but he will do."

James' description of the influence of Paris on American painters of the late 19th century also still rings true: "It sounds like a paradox, but it is a very simple truth, that when today we look for ‘American art' we find it mainly in Paris," he wrote in 1887. "When we find it out of Paris, we at least find a great deal of Paris in it."

The City of Light shone like a beacon for many American artists, who felt better appreciated there than in their own business-preoccupied country. By the late 1880s, it was estimated that one in seven of the 7,000 Americans living in Paris were artists or art students. For women especially, the French capital offered an intoxicating freedom. "They were Americans, so they weren't bound by the conventions of French society," says Erica E. Hirshler of Boston's Museum of Fine Arts, one of the exhibition's three curators. "And they were no longer in America, so they escaped those restrictions too."

A striking self-portrait by Ellen Day Hale, painted just before she returned to her native Boston, makes the point. Seen from below, her head tilted slightly, Hale is every bit the flâneur—that disengaged but acutely perceptive stroller through Parisian crowds celebrated by poet Charles Baudelaire as the archetypal modern figure (by which he, of course, meant "man"). "It's an amazing portrait for a woman in 1885 to be that forthright and direct and determined-looking," says Hirshler.

In America, only Philadelphia and New York City could provide the kind of rigorous artistic training, based on observation of the nude model, available in the French capital. "Go straight to Paris," the prominent Boston painter William Morris Hunt told a 17-year-old art student. "All you learn here you will have to unlearn." Paris offered the aspiring artist three educational options. Most renowned (and the hardest to enter) was the École des Beaux-Arts, the venerable state-owned institution that gave tuition-free instruction—under the supervision of such Salon luminaries as artists Jean-Léon Gérôme and Alexandre Cabanel—to students admitted by a highly competitive examination. A parallel system of private academies dispensed comparable training for a fee. (Women, who were barred from the École until 1897, typically paid twice what men were charged.) The most successful of these art-education entrepreneurs was Rodolphe Julian, whose Académie Julian drew so many applicants that he would open several branches in the city. Finally, a less formal avenue of tutelage was offered by painters who examined and criticized student work, in many cases for the pure satisfaction of mentoring. (Students provided studio space and models.)

The feeling of being an art student at the time is convincingly rendered in Jefferson David Chalfant's jewel-like 1891 depiction of an atelier at the Académie Julian (p. 81). Clusters of men at easels gather around nude models, who maintain their poses on plank tables that serve as makeshift pedestals. Weak rays of sunshine filter through the skylight, illuminating student drawings and paintings on the walls. A veil of cigarette smoke hangs in air so visibly stuffy that, more than a century later, it can still induce an involuntary cough.

Outside the halls of academe, starting in the 1860s, the French Impressionists were redefining artistic subject matter and developing original techniques. In their cityscapes, they recorded prostitutes, lonely drinkers and alienated crowds. In their landscapes, they rejected the conventions of black shading and gradually modulated tones in favor of staring hard at the patterns of light and color that deliver an image to the eye and reproducing it with dabs of paint. Even when depicting something as familiar as a haystack, Claude Monet was rethinking the way in which a paintbrush can render a visual experience.

Taking advantage of their proximity, many of the young American artists in Paris journeyed to the epicenter of the Impressionist movement, Monet's rural retreat northwest of the city at Giverny. In 1885, Sargent and another young painter, Willard Metcalf, may have been the first Americans to visit Monet there. In The Ten Cent Breakfast, which Metcalf painted two years later, he brought his Académie Julian training to bear on the thriving social scene of visitors at the Hotel Baudy, a favorite Giverny hangout. However, in these surroundings, Impressionism evidently impressed him: his 1886 Poppy Field (Landscape at Giverny) owes a great deal to Monet's Impressionist style (and subject matter). By the summer of 1887, other American artists, including Theodore Robinson and John Leslie Breck, were making the pilgrimage.

Monet preached the virtue of painting scenes of one's native surroundings. And although Sargent remained a lifelong expatriate, many of the Americans who studied in France returned to the United States to develop their own brand of Impressionism. Some started summer colonies for artists—in Cos Cob and Old Lyme, Connecticut; Gloucester, Massachusetts; and East Hampton, New York—that resembled the French painters' haunts of Pont-Aven, Grez-sur-Loing and Giverny. These young artists were much like the American chefs of a century later, who, having learned the importance of using fresh, seasonal ingredients from the French pioneers of nouvelle cuisine, devised menus that highlighted the California harvest, yet still somehow tasted inescapably French. A Gallic aroma clings to Robinson's Port Ben, Delaware and Hudson Canal (1893)—with its cloud-flecked sky and flat New York State landscape evoking the northern French plain—as well as to Breck's view of suburban Boston, Grey Day on the Charles (1894), with its lily pads and rushes reminiscent of Giverny.

The Impressionism that the Americans brought home from France was decorative and decorous. It reiterated techniques that had been pioneered in France and avoided the unpleasant truths of American urban life. "What's distinctive about American Impressionism, for better or worse, is that it's late," says H. Barbara Weinberg of the Metropolitan Museum, one of the show's co-curators. "French Impressionism is presented to these artists fully formed as something to develop and adapt. They are not there on the edge of invention." The movement appeared in America just as, two decades old, it was losing momentum in France. "By 1886, Renoir is rejecting even his own relatively conservative Impressionist efforts, and Seurat is challenging Impressionism with Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte," says Weinberg. But in America, 1886 was the high-water mark of Impressionism—the year of the landmark exhibitions staged in New York City by Paul Durand-Ruel, the chief Parisian dealer of French Impressionism, providing an opportunity for those unfortunates who had never been to France to see what all the commotion was about.

For many visitors, the revelation of the current exhibition will be an introduction to some artists whose reputations have faded. One of these is Dennis Miller Bunker, who seemed destined for great things before his death from meningitis in 1890 at the age of 29. Bunker had studied under Gérôme at the École des Beaux-Arts, but he developed his Impressionist flair only after leaving France, probably through his friendship with Sargent (both were favorites of the wealthy Boston collector Isabella Stewart Gardner) and from a familiarity with the many Monet paintings he saw in public collections once he settled in Boston. His Chrysanthemums of 1888 depicts a profusion of potted flowers in a greenhouse at the Gardners' summer home. With its boldly stippled brushwork and bright masses of color, the energetic Chrysanthemums is a pioneering work.

Although numerous American artists came to view themselves as Impressionists, only one would ever exhibit with the French Impressionists themselves. Mary Cassatt was in many ways a singular phenomenon. Born in Pittsburgh in 1844, she moved with her affluent family to Europe as a child and spent most of her life in France. A display of Degas pastels she saw at age 31 in a Parisian dealer's window transformed her vision. "I used to go and flatten my nose against that window and absorb all I could of his art," she later wrote. "It changed my life. I saw art then as I wanted to see it." She struck up a friendship with the cantankerous older painter, and after the Salon rejected her work in 1877, he suggested that she show with the Impressionists instead. At their next exhibition, which wasn't held until 1879, she was represented by 11 paintings and pastels. "She has infinite talent," Degas proclaimed. She went on to participate in three more of their shows.

"When Cassatt is good, she easily holds her own against her French counterparts," Weinberg says. "She speaks Impressionism with a different accent, although I don't know that you can say with an American accent, because she wasn't in America much after 1875." Cassatt's subject matter diverged from the usual Impressionist fare. As a woman, she could not freely visit the bars and cabarets that Degas and his colleagues immortalized. Her specialty was intimate scenes of mothers with their children.

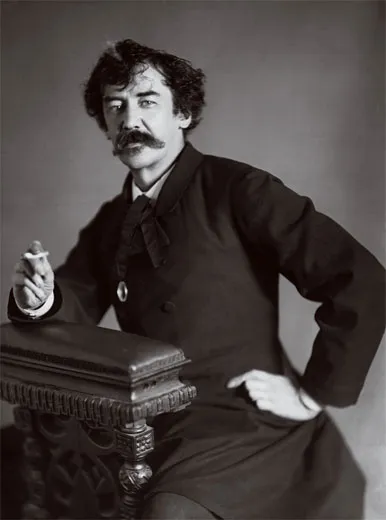

Yet even Cassatt, notwithstanding her great accomplishments, was more follower than leader. There was just one truly original American painter in Paris: James Abbott McNeill Whistler. Older than most of the other artists in this exhibition and, following an early childhood in New England, a lifelong resident of Europe (mainly London and Paris), he was a radical innovator. Not until the Abstract Expressionists of mid-20th-century New York does one encounter other American artists with the personality and creativity to reverse the direction of influence between the continents. "He is ahead of the pack—among the Americans and also among the French," says Weinberg. "What he does is go from Realism to Post-Impressionism without going through Impressionism." The exhibition documents how startlingly rapid that transformation was—from the realistic seascape Coast of Brittany (1861), reminiscent of his friend, Gustave Courbet; to the symbolically suggestive Symphony in White, No. 1: The White Girl (1862), a painting of a wide-eyed young woman (his mistress, Jo Hiffernan); and, finally, to the emergence, in 1865, of a mature, Post-Impressionist style in such paintings as The Sea and Harmony in Blue and Silver: Trouville (not included in the New York version of the show), in which he divides the canvas into broad bands of color and applies the paint as thinly, he liked to say, as breath on a pane of glass. From then on, Whistler would think of subject matter merely as something to be worked on harmonically, as a composer plays with a musical theme to produce a mood or impression. The purely abstract paintings of Mark Rothko lie just over Whistler's horizon.

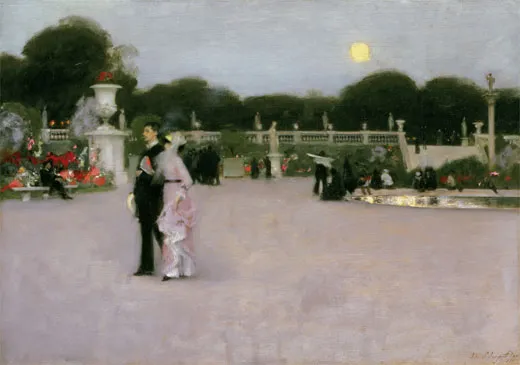

However, as this exhibition makes clear, most of the late-19th-century American painters in Paris were conformists, not visionaries. The leading American practitioner of Impressionism was Childe Hassam, who shared Whistler's love of beauty but not his avant-garde spirit. Arriving in Paris in 1886 at the relatively advanced age of 27, Hassam was already a skilled painter and found his lessons at the Académie Julian to be deadening "nonsense." He chose instead to paint picturesque street scenes in the Impressionist style. Returning to America in 1889, he paid lip service to the idea that an artist should document modern life, however gritty, but the New York City he chose to portray was uniformly attractive, and the countryside, even more so. Visiting his friend, poet Celia Thaxter, on the Isles of Shoals in New Hampshire, he painted a series of renowned flower pictures in her cutting garden. Even in this idyllic spot, he had to edit out tawdry bits of encroaching commercial tourism.

Hassam adamantly denied that he had been directly influenced by Monet and the other Impressionists, implicating instead the earlier Barbizon School of French painters and Dutch landscape artist Johan Barthold Jongkind. But his disavowal of Monet was disingenuous. Hassam's celebrated "flag paintings"—scenes of Fifth Avenue draped in patriotic bunting, which he began in 1916 after a New York City parade in support of the Allied cause in World War I—drew their lineage from Monet's The Rue Montorgeuil, Paris, Festival of June 30, 1878, which was exhibited in Paris in 1889, while Hassam was a student there. Unfortunately, something got lost in the translation.The rippling excitement and confined energy of Monet's scene becomes static in Hassam's treatment: still beautiful, but embalmed.

Indeed by the time of Hassam's flag paintings, the life had gone out of both the French Academy and French Impressionism. Alluring as always, Paris remained the capital of Western art, but the art had changed. Now Paris was the city of Picasso and Matisse. For the new generation of modern American painters flocking to Paris, "academic" was a pejorative. They probably would have found the portrait of a society beauty in a low-cut gown a little bit conventional and not at all shocking.

Arthur Lubow lives in Manhattan and is a contributing writer on cultural subjects to the New York Times Magazine.