An Osage Family Reunion

With the help of Smithsonian model makers, the tribal nation is obtaining busts of ancestors who lived at a pivotal moment in their history

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ATM-Osage-Nation-Albert-Penn-relatives-631.jpg)

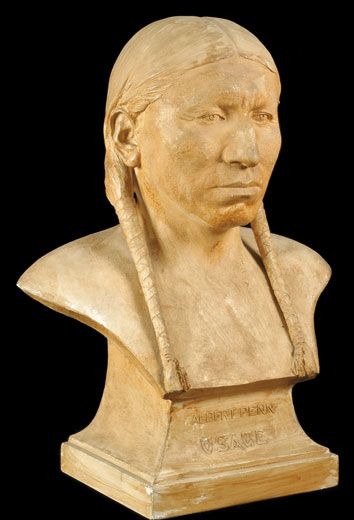

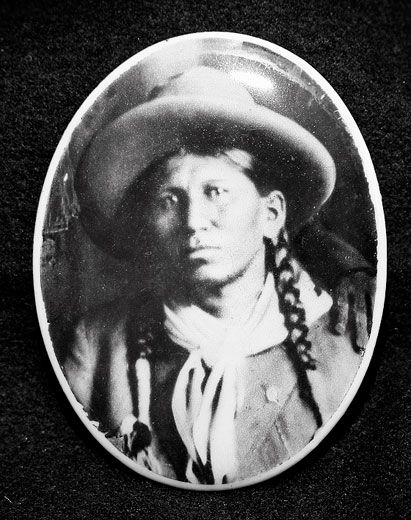

“I don’t know how to explain seeing my grandfather for the first time,” says Evelyn Taylor, an Osage tribal member from Bartlesville, Oklahoma. As a child, she had heard stories that a plaster bust of her family patriarch, Albert Penn, resided somewhere in the Smithsonian Institution. Taylor finally came face to face with her grandfather at the National Museum of Natural History one sunny June morning in 2004. “I was in awe,” she says.

The bust is one of ten commissioned in the early 20th century by Ales Hrdlicka, the Smithsonian’s curator for physical anthropology. Striving to capture even the most subtle details, the sculptor, Frank Micka, had his subjects photographed, then covered their faces, ears and even their necks and upper chests with wet plaster to make casts. He made two face casts in 1904, when an Osage delegation visited Washington, D.C. In 1912, Micka visited tribal members in Oklahoma and made eight busts, which were part of a Smithsonian display on Native American culture at a 1915 exhibition in San Diego. During the past seven years, the Smithsonian has made reproductions of the busts for the Osage Tribal Museum in Pawhuska, Oklahoma. The tenth and final copy, depicting tribeswoman Margaret Goode, will be unveiled at the Osage museum early next year.

The busts represent a turning point in the history of the Osage. Early explorers, including Lewis and Clark, wrote in awe about the six-foot-tall tribesmen with tattooed bodies and pierced ears adorned with shells and bones. By 1800, the Osage had defeated rival tribes and controlled a swath of territory in modern-day Missouri, Arkansas, Kansas and Oklahoma.

The federal government, however, saw Osage lands as a barrier to westward expansion. Throughout the 19th century, a series of treaties whittled away at Osage territory, and in 1872 the remaining members of the tribe, who lived mostly in Kansas, were relocated to an Oklahoma reservation. One of the busts depicts Chief Lookout—the longest-serving chief of the Osage Nation—who was 12 years old when he and his people made that final journey to Oklahoma.

After the 1915 exhibition, the Osage busts were brought to Washington, D.C., where they sat in storage. But Albert Penn’s descendants had heard about his likeness, and in 1958, when Taylor was a child, the family loaded up the car and left Oklahoma to see the sculpture for themselves. “We made it as far as Kentucky and had a head-on collision,” she says. “It seemed like it was just not meant to be.”

Years later, she married Larry Taylor, part-Cherokee and an amateur historian, and he resumed the search. “I pretty well came to the conclusion that it was probably a one-time thing that had since been gotten rid of,” he says. In a last-ditch effort, he sent an e-mail to David Hunt, an anthropologist at Natural History, picking his name at random from a list of museum employees. As it happened, Hunt was responsible for the Native American busts. Indeed, Hunt told Larry that he had often wondered about the descendants of the people depicted by the sculptures. Hunt and his colleagues made a copy of Penn’s bust for the Osage Tribal Museum. Soon, Larry says, other tribal members approached both him and Evelyn, saying they wanted reproductions of their ancestors’ busts.

Copying the busts is the job of the Smithsonian’s Office of Exhibits Central, which builds museum displays. Carolyn Thome, a model maker, fashions rubber molds of the originals, then forms the bust itself out of a plastic resin containing bronze powder, which lends a metallic luster that emphasizes the finished product’s facial features. The $2,000 to $3,000 cost of reproducing each bust is covered by the Osage museum and families.

Evelyn still gets chills when she sees her tribe’s ancestors. “They’re just there looking at you,” she says. “And now, not only is it the elders who know about these, but the generations yet to come.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)