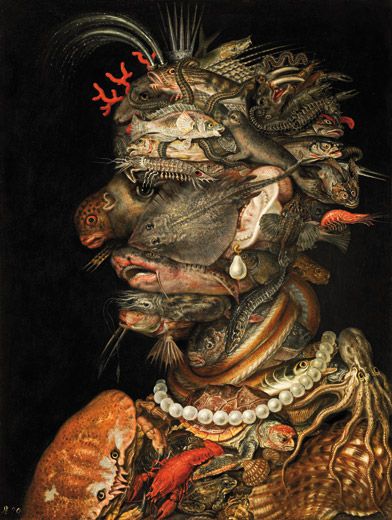

Arcimboldo’s Feast for the Eyes

Renaissance artist Giuseppe Arcimboldo painted witty, even surreal portraits composed of fruits, vegetables, fish and trees

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Arcimboldo-Rudolf-II-631.jpg)

The job of a renaissance court portraitist was to produce likenesses of his sovereigns to display at the palace and give to foreign dignitaries or prospective brides. It went without saying the portraits should be flattering. Yet, in 1590, Giuseppe Arcimboldo painted his royal patron, the Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II, as a heap of fruits and vegetables (opposite). With pea pod eyelids and a gourd for a forehead, he looks less like a king than a crudité platter.

Lucky for Arcimboldo, Rudolf had a sense of humor. And he had probably grown accustomed to the artist’s visual wit. Arcimboldo served the Hapsburg family for more than 25 years, creating oddball “composite heads” made of sea creatures, flowers, dinner roasts and other materials.

Though his work was forgotten for centuries, Arcimboldo is enjoying a personal renaissance, with shows at major European museums. At the Louvre, a series of Arcimboldo paintings is among the most popular in the collection. Sixteen of the jester’s best works, including the Louvre series, are on display until January 9 at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., the first major American exhibition of its kind.

“We wanted people to have the experience that the emperors in the Hapsburg court had,” says David Alan Brown, a National Gallery curator. “To have the same pleasure, as if they were playing a game, to first see what looks like a head and then discover on closer inspection that this head is made of a myriad of the most carefully observed flowers, vegetables, fruits, animals and birds.”

The show is also a chance to get inside Arcimboldo’s own head, itself a composite of sorts. Part scientist, part sycophant, part visionary, Arcimboldo was born in 1526 in Milan. His father was an artist, and Giuseppe’s early career suggests the standard Renaissance daily grind: he designed cathedral windows and tapestries rife with angels, saints and evangelists. Though apples and lemons appear in some scenes, the produce is, comparatively, unremarkable. Rudolf’s father, Maximilian II, the Hapsburg archduke and soon-to-be Holy Roman Emperor, welcomed the painter in his Vienna court in the early 1560s. Arcimboldo remained with the Hapsburgs until 1587 and continued to paint for them after his return to Italy.

Perhaps not accidentally, Arcimboldo’s long absence from Milan coincided with the reign there of an especially humorless Milanese archbishop who cracked down on local artists and would have had little patience for produce portraiture. The Hapsburgs, on the other hand, were hungry for imaginative works. Members of the dynasty were quick to emphasize their claims to greatness and promoted an avant-garde atmosphere in their court, which teemed with intellectuals.

Arcimboldo, according to an Italian friend, was always up to something capricciosa, or whimsical, whether it was inventing a harpsichord-like instrument, writing poetry or concocting costumes for royal pageants. He likely spent time browsing the Hapsburgs’ private collections of artworks and natural oddities in the Kunstkammer, considered a predecessor of modern museums.

The first known composite heads were presented to Maximilian on New Year’s Day 1569. One set of paintings was called The Four Seasons, and the other—which included Earth, Water, Fire and Air—The Four Elements. The allegorical paintings are peppered with visual puns (Summer’s ear is an ear of corn) as well as references to the Hapsburgs. The nose and ear of Fire are made of fire strikers, one of the imperial family’s symbols. Winter wears a cloak monogrammed with an “M,” presumably for Maximilian, that resembles a garment the emperor actually owned. Earth features a lion skin, a reference to the mythological Hercules, to whom the Hapsburgs were at pains to trace their lineage. Many of the figures are crowned with tree branches, coral fragments or stag’s antlers.

The paintings were meant to amuse, but they also symbolize “the majesty of the ruler, the copiousness of creation and the power of the ruling family over everything,” says Thomas DaCosta Kaufmann, an art history professor at Princeton who is author of Arcimboldo:Visual Jokes, Natural History, and Still-Life Painting. “In some ways it’s just humor, but the humor resolves itself in a serious way.” Maximilian so liked this imagery that he and other members of his court dressed up as the elements and seasons in a 1571 festival orchestrated by Arcimboldo. (The emperor played winter.)

This was the dawn of disciplines such as botany and zoology, when artists including Leonardo da Vinci—Arcimboldo’s predecessor in Milan—pursued natural studies. Arcimboldo’s composites suggest a scientific fluency that highlighted his patron’s learnedness. “Every plant, every grass, every flower is recognizable from a scientific point of view,” says Lucia Tomasi Tongiorgi, an art historian at the University of Pisa. “That’s not a joke. It’s knowledge.” The Hapsburgs “were very interested in the collection of nature,” Kaufmann says. “They had fishponds. They had pet lions.”

Even seemingly pedantic botanical details bear out the theme of empire. Arcimboldo’s composites incorporated exotic specimens, such as corn and eggplant, which sophisticated viewers would recognize as rare cultivars from the New World and beyond, where so many European rulers hoped to extend their influence.

One modern critic has theorized that Arcimboldo suffered from mental illness, but others insist he had to have had his wits about him to win and retain favor in such rarefied circles. Still others have suggested he was a misunderstood man of the people—rather than fawning over the Hapsburgs, he mocked them in plain sight. This seems unlikely, though; scholars now believe that Arcimboldo falsified his ties to a powerful Italian family in an attempt to pass himself off as nobility.

The Kunstkammer was looted during the Thirty Years’ War (1618-48), and a number of Arcimboldo’s paintings were carried off to Sweden. The composite heads disappeared into private collections, and Arcimboldo would remain rather obscure until the 20th century, when painters from Salvador Dali to Pablo Picasso are said to have rediscovered him. He has been hailed as the grandfather of Surrealism.

His works continue to surface, including Four Seasons in One Head, painted not long before his death in 1593 at 66. The National Gallery acquired the painting from a New York dealer this past fall. It’s the only undisputed Arcimboldo owned by an American museum. Originally a gift to one of Arcimboldo’s Italian friends, Four Seasons may be Arcimboldo’s reflection on his own life. The tree-trunk face is craggy and comical, but a jaunty pair of red cherries dangles from one ear, and the head is heaped with grape leaves and apples—laurels the artist perhaps knew he deserved.

Abigail Tucker is the magazine’s staff writer.