An Artist Imagines the Future of Humans in Space

Through manipulated photographs and video, Michael Najjar tackles the meaning of space travel

When visual artist Michael Najjar took a plane to more than 60,000 feet in the upper atmosphere, he knew the trip would be intense. The Russian MiG-29 Fulcrum jet fighter aircraft he rode was originally designed for the Soviet Union's air force during the late 1970s. Now the jet carries passengers high into the stratosphere where the Earth's curvature is visible and the sky turns dark enough to see stars at midday. The flight is advertised as "probably the mightiest experience in the world."

Najjar had some knowledge of the maneuvers planned—flight at supersonic speed, barrel rolls, tail slides and Immelman turns. And yet, he says, "I was not at all mentally prepared for what was going to happen in this flight. I was very overwhelmed." During the 50-minute flight, he nearly lost consciousness, frequently couldn’t tell up from down and experienced acceleration more than seven times the normal pull of gravity on Earth. "After 50 minutes, I was really done," he adds.

Originally from Heidelberg, Germany, the 49-year-old Najjar got his start as an artist at Berlin's Bildo Academy for Media Arts. Now, the Berlin resident regularly seeks out the type of extreme physical and mental challenge he faced on that flight. He is not an adrenaline junkie, rather his work depends on pushing himself. He is interested in "the kind of virgin state of your brain when you have no idea what is going to happen." He draws on that state to create his art. Past works have taken him on a trek up the slopes of Mount Aconcagua in the Andes, the highest mountain in the world outside of the Himalayas, to use the photographs of mountainscapes to provide the basis for visualizations of global stock indices in his high altitude series. It was only the second mountain he had ever climbed. Another series, netropolis, took him to the tops of the tallest buildings in the world where he explored the interconnectedness of urban life and the future of cities.

Najjar will experience the strain of excess g-forces again if all goes as he plans. The stratospheric flight was just one step in his mission to be the first artist in space, a quest he is documenting in his ongoing series outer space.

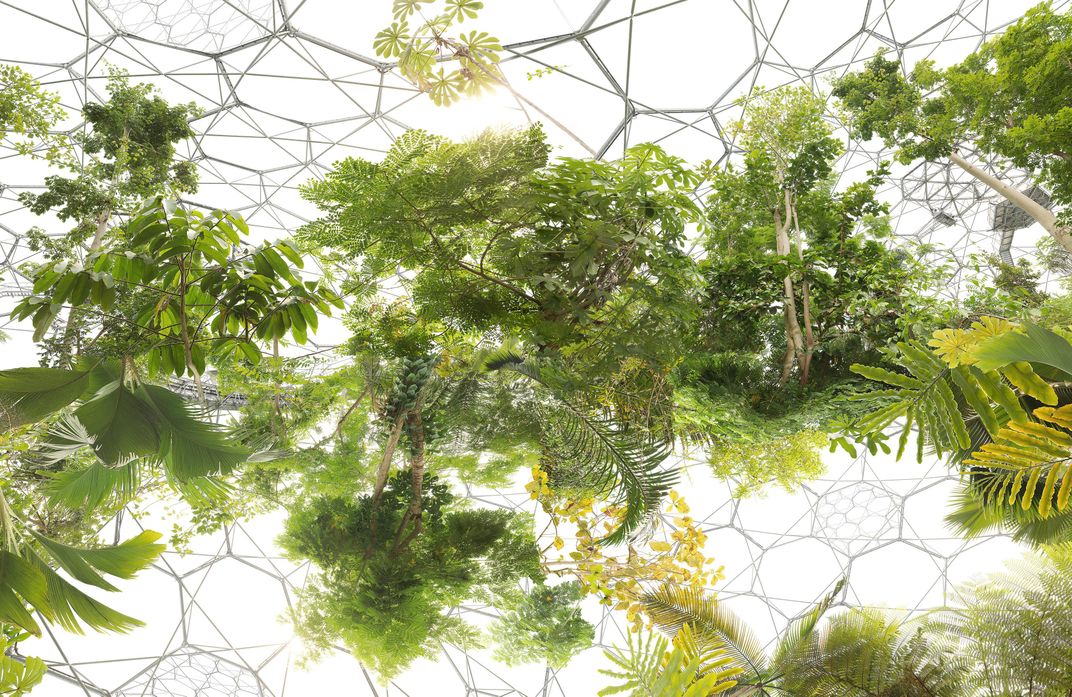

On March 31, outer space opens at the Benrubi Gallery in New York City. Through photography, digitally manipulated images and video, Najjar explores the technological innovation surrounding the latest developments in space flight. These developments are the reusable rockets, futuristic spaceports and other advances that may someday make space travel a common experience. On his website, Najjar writes: "By leaving our home planet and flying to the moon or other planets, we change our understanding of two of the most fundamental questions confronting humanity—who we are and where we come from."

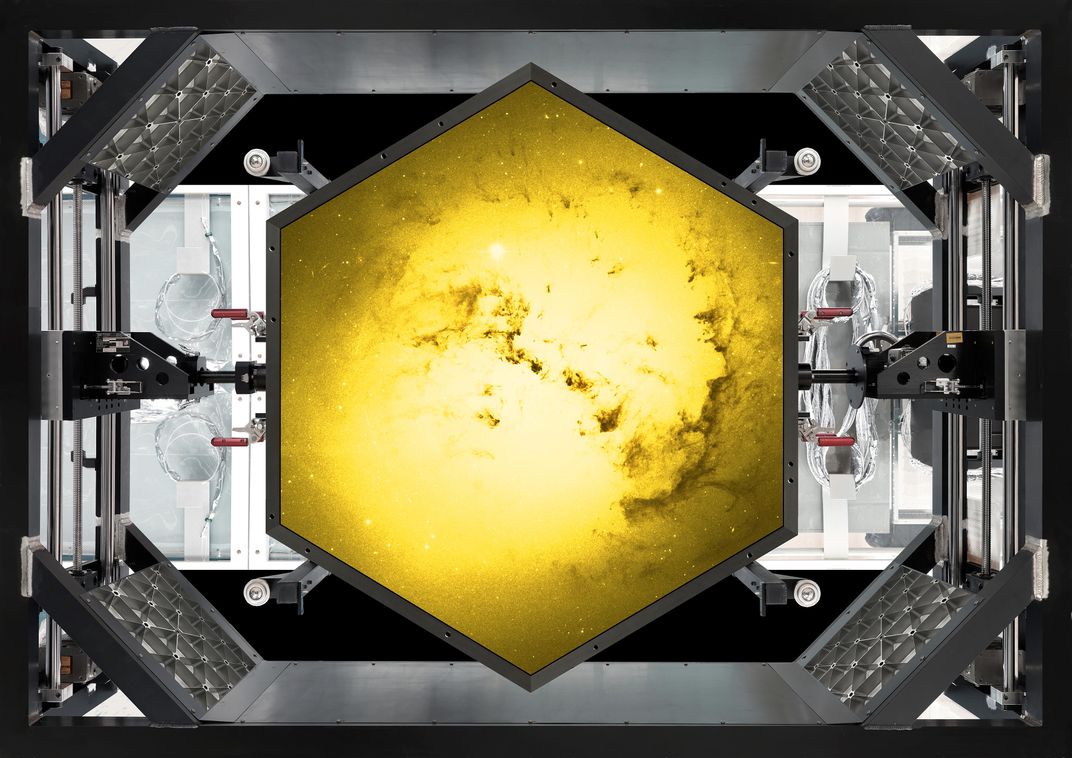

The series of more than two dozen images (thus far) includes one of a radiantly golden hexagon framed by crisply-lit hardware, a mirror from the under-construction James Webb Space Telescope, with the dark filaments of some galaxy reflected in its face. In another image, a person hangs upside down from the frame's edge, wearing a flight suit, breathing apparatus and violet-tinged goggles. It's a self-portrait Najjar took at nearly 64,000 feet, as the MiG-29 flew 1,118 miles per hour.

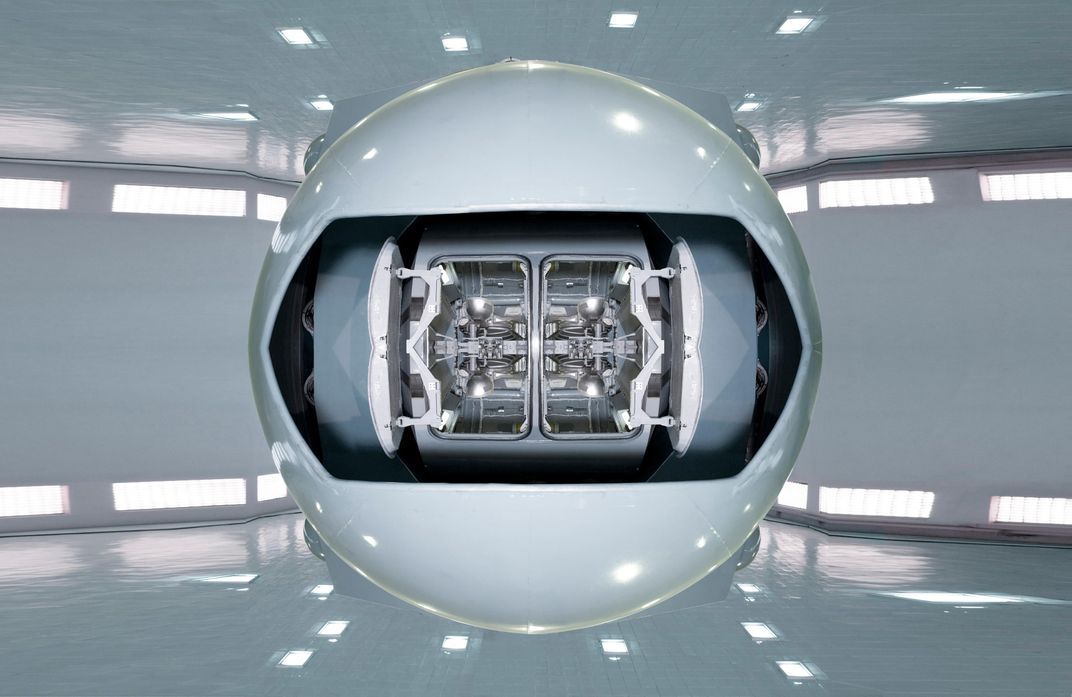

The videos complement the still images. One, equilibrium, features a manipulated, duplicated view of Najjar during the flight that makes his twinned helmet-covered heads look like the eyes of a beetle with a shiny carapace caught between two spheres of blue—the curve of the Earth doubled. Voices on the radio crackle over the sound of the jet's engines.

Other images show the constellation of debris from broken satellites and space missions surrounding the Earth, the giant telescope in Chile known as the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), a fanciful vision of the surface of Europa and an imagining of the Moon under a regime of helium-3 mining. "The series tries to open certain windows, certain frames to make people understand that the Earth is not the limit of human existence,” Najjar explains.

But Najjar doesn't make the mistake of looking at the future through rose-colored glasses. He also includes serious anomaly, an image of the crippled and crumbled Virgin Galactic's SpaceShipTwo after it crashed in the Mojave Desert, killing the co-pilot, Michael Alsbury, and seriously injuring pilot Peter Siebold. The tragedy must have resonated for Najjar: His plan to become the first artist in space relies on transportation by Virgin Galactic itself.

As the series hints, technology can be an undeniable boon, but it also comes with unforeseen consequences and alterations to everyday human life. This theme runs throughout all of Najjar’s experience-based artwork. "We are living in a time where personal and actual experiences are getting less and less everyday," he says. The increasingly digital world can open up new possibilities and connections but the "virtual data flow, virtual perceptions and virtual friendships" that are so common now can sometimes overshadow unique, physical experiences, he says.

Neither utopian or a dystopian, Najjar's work explores both sides of the future. "In general, I'm looking very optimistically into the future and the possibilities of technological progress," he says. "But I also see a lot of problems and dangers that are arising with new technologies."

The series, started in 2011, isn't yet completed. First, Najjar has upcoming Virgin Galactic test flights in the works for later this year or in 2017. Then, hopefully the trip to space itself. He says that people have asked him what he will photograph when he reaches space. But he explains that it is not as important as what he will see: The many photographs from astronauts and satellites have given us some idea of what the Earth looks like once you have loosened its tethers of gravity and atmosphere. Instead the whole process, from boarding the spaceship to blasting off to reaching microgravity, intrigues him.

Najjar sees his role as an artist as one full of privilege and responsibility. So far, just more than 530 people have been to space, but they were all professionals of space travel. They were military, scientists and engineers who may have a "limited language" to tell of their travels, Najjar says. "Artists have different tools,” he adds, “and can find ways to tell about the translations and transportations they experience."

Najjar hopes to learn what it means to leave the habitat where we all live. Then, he'll come back to tell us about it.

The series has shown in Spain, Italy and Najjar's home country of Germany. Now American viewers will get a chance to view a selection of 9 or 10 images and three videos from outer space at the Benrubi Gallery in New York City from March 31 through May 14, 2016. Najjar's work is also perusable on his website.