Barbara Kruger’s Artwork Speaks Truth to Power

The mass media artist has been refashioning our idioms into sharp-edged cultural critiques for three decades—and now brings her work to the Hirshhorn

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Profile-Barbara-Kruger-631.jpg)

Barbara Kruger is heading to Washington bearing the single word that has the power to shake the seat of government to its roots and cleave its sclerotic, deep-frozen deadlock.

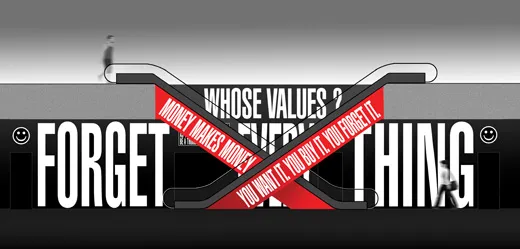

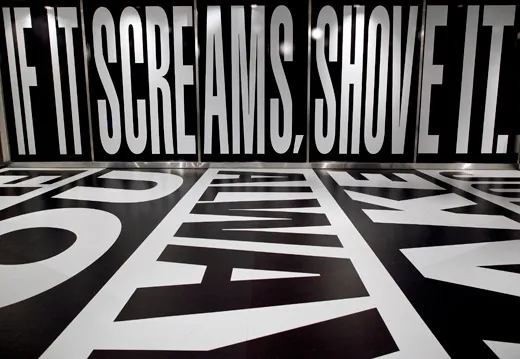

What is the word? Well, first let me introduce Barbara Kruger. If you don’t know her name, you’ve probably seen her work in art galleries, on magazine covers or in giant installations that cover walls, billboards, buildings, buses, trains and tram lines all over the world. Her new installation at the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, D.C., scheduled to open August 20—the one that focuses on that powerful, power-zapping word (yes, I will tell you what it is)—will be visible from two floors of public space, filling the entire lower lobby area, also covering the sides and undersides of the escalators. And when I say floors, I mean that literally. Visitors will walk upon her words, be surrounded by walls of her words, ride on escalators covered with her words.

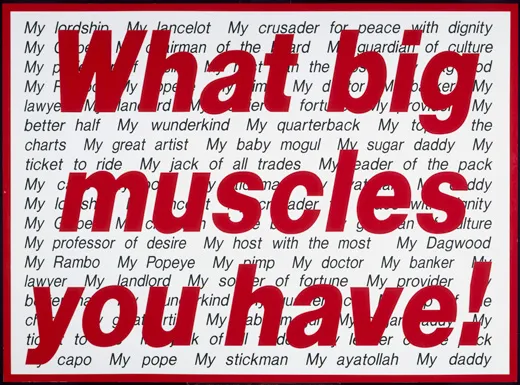

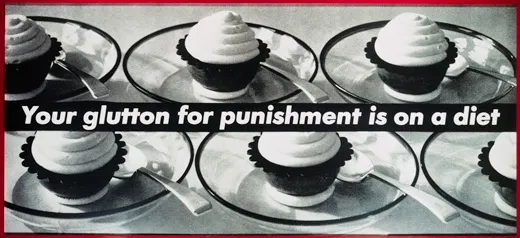

What’s the best way to describe her work? You know abstract expressionism, right? Well, think of Kruger’s art as “extract expressionism.” She takes images from the mass media and pastes words over them, big, bold extracts of text—aphorisms, questions, slogans. Short machine-gun bursts of words that when isolated, and framed by Kruger’s gaze, linger in your mind, forcing you to think twice, thrice about clichés and catchphrases, introducing ironies into cultural idioms and the conventional wisdom they embed in our brains.

A woman’s face in a mirror shattered by a bullet hole, a mirror on which the phrase “You are not yourself” is superimposed to destabilize us, at least momentarily. (Not myself! Who am I?) Her aphorisms range from the overtly political (Your body is a battleground) to the culturally acidic (Charisma is the perfume of your gods) to the challengingly metaphysical (Who do you think you are?).

Kruger grew up middle class in Newark, New Jersey, and her first job was as a page designer at Mademoiselle. She turned out to be a master at using type seductively to frame and foreground the image and lure the reader to the text.

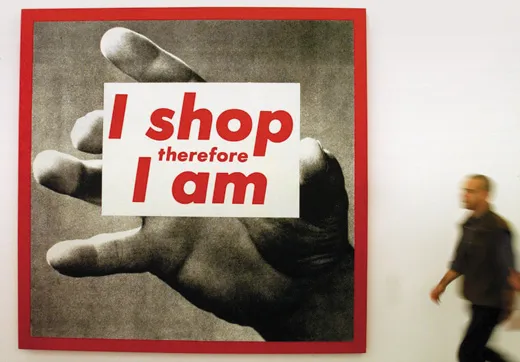

The dream-machine magazine empire of Condé Nast (which also publishes Vogue, Vanity Fair and Glamour)—the dizzyingly seductive and powerful fusion of fashion, class, money, image and status—represented both an inspiration and an inviting target. The fantasy-fueled appetite to consume became Kruger’s enduring subject when she left for the downtown art world, where many of her early pieces were formal verbal defacements of glossy magazine pages, glamorous graffiti. One of her most famous works proclaimed, “I shop therefore I am.”

Kruger keeps her finger tightly pressed to the pulse of popular culture. So it shouldn’t have surprised me as much as it did when, in the middle of a recent lunch at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, she practically leapt out of her chair and pointed excitedly to someone on the plaza outside. “It’s the hairdresser from Bravo!” she exclaimed excitedly. When I professed ignorance, Kruger explained, “She’s on this Bravo reality series where she goes into failing hair salons and fixes them up.” (I later learned the woman was Tabatha, from a show called “Tabatha Takes Over.”)

In addition to being a self-proclaimed “news junkie” and bookmarking the Guardian and other such serious sites, Kruger is a big student of reality shows, she told me. Which makes sense in a way: Her work is all about skewed representations of reality. How we pose as ourselves. She discoursed knowingly about current trends in reality shows, including the “preppers” (preparing for the apocalypse) and the storage wars and the hoarder shows. Those shows, she thinks, tell us important things about value, materialism and consumerism.

Kruger has immersed herself in such abstruse thinkers as Walter Benjamin, the prewar post-modernist (“Did you know he was a compulsive shopper? Read his Moscow Diary!”), and Pierre Bourdieu, the influential postmodern French intellectual responsible for the concept of “cultural capital” (the idea that status, “prestige” and media recognition count as much as money when it comes to assessing power). But she knows theory is not enough. She needs to wade into the muddy river of American culture, panning for iconic words and images like a miner looking for gold in a fast-running stream, extracting the nuggets and giving them a setting and a polish so they can serve as our mirror.

Christopher Ricks, a former Oxford professor of poetry, once told me the simplest way to recognize value in art: It is “that which continues to repay attention.” And Barbara Kruger’s words not only repay but demand attention from us. Her work has become more relevant than ever at a time when we are inundated by words in a dizzying, delirious way—by the torrent, the tidal wave, the tsunami unleashed by the Internet. “What do you read, my lord?” Polonius asks Hamlet. “Words, words, words,” he replies. Meaningless words. And that is what they threaten to become as we drown in oceans of text on the web. Pixels, pixels, pixels.

In a virtual world, virtual words are becoming virtually weightless, dematerialized. The more words wash over us, the less we understand them. And the less we are able to recognize which ones are influencing us—manipulating us subtly, invisibly, insidiously. Barbara Kruger rematerializes words, so that we can read them closely, deeply.

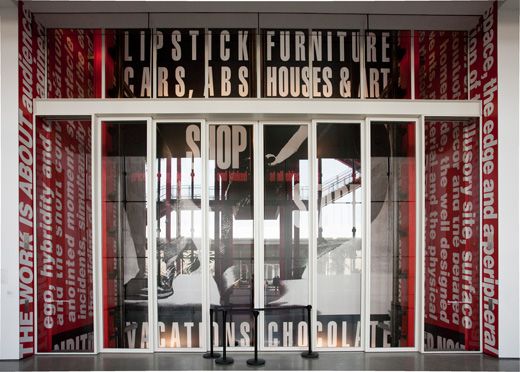

I arrived early for our lunch at LACMA because I wanted to see the installation she’d done there, covering a massive three-story glassed-in garage elevator with an extraordinary profusion of words and phrases. Among these words and phrases is a long, eloquent description of the work itself:

“The work is about...audience and the scrutiny of judgment...fashion and the imperialism of garments, community and the discourse of self-esteem, witnessing and the anointed moment, spectacle and the enveloped viewer, narrative and the gathering of incidents, simultaneity and the elusive now, digitals and the rush of the capture.” There’s much, much more just in case we miss any aspect of what “the work is about.” Indeed the work is in part about a work telling itself what it’s about.

Notice how much of it is about extraction: extraction of “the anointed moment” from the stream of time (and stream of consciousness), finding a way to crystallize the “elusive now” amid the rush of “digitals.” It’s the Kruger of all Krugers.

But gazing at this, I missed the single most important extraction—or at least its origin. The elephant in the installation.

It was up there, dominating the top of the work, a line written in the biggest, boldest, baddest letters. The central stack of words is superimposed over the brooding eyes and the advancing shoes of a man in what looks like a black-and-white movie still. His head is exploding into what looks like a blank white mushroom cloud, and on the cloud is written: “If you want a picture of the future, imagine a boot stomping on a human face forever.”

Have a nice day, museumgoers!

Not long after, I was seated in LACMA’s sleek restaurant with Kruger, whose waterfalls of delicate curls give her a pre-Raphaelite, Laurel Canyon look. (She lives half the year in L.A. teaching at UCLA, half the year in New York City.) One of the first things I asked about was that boot-stomping line on the elevator installation. “I was glad to see someone as pessimistic as me about the future. Where’d you get that quote?”

“It’s George Orwell,” she replied. Orwell, of course! It’s been a long time since I’ve read 1984, so I’m grateful that she extracted it, this unmediated prophecy of doom from someone whose pronouncements have, uncannily and tragically, kept coming true. And it reminded me that she shares with Orwell an oracular mode of thought—and a preoccupation with language. Orwell invented Newspeak, words refashioned to become lies. Kruger works similarly, but in the opposite direction. Truespeak? Kru-speak?

“Unfortunately,” she went on to remark ominously of the Orwell quote, “it’s still very viable.”

For some, Kruger has had a forbidding aura, which is probably because of the stringent feminist content of some of her more agitprop aphorisms, such as “Your body is a battleground,” which features a woman’s face made into a grotesque-looking mask by slicing it in half and rendering one side as a negative. When I later told people I’d found Kruger down-to-earth, humorous and even kindly, those who knew her readily agreed, those who knew only her early work were a bit surprised.

But she’s made a point of being more than an ideologue. “I always say I try to make my work about how we are to one another,” she told me.

That reminded me of one of her works in which the word “empathy” stood out.

“‘How we are to each other,’” I asked. “Is that how you define empathy?”

“Oh,” she replied with a laugh, “well, too often it’s not [how we are to each other].”

“But ideally...we’re empathetic?”

“No,” she said, “I don’t know if that’s been wired into us. But I mean I’ve never been engaged with the war of the sexes. It’s too binary. The good versus the bad. Who’s the good?”

It’s a phrase she uses often: “too binary.” She’d rather work in multiple shades of meaning and the ironies that undercut them.

All of which brings us to her upcoming installation invasion of Washington and that potent, verboten word she wants to bring to Washington’s attention. The magic word with the secret power that is like garlic to Dracula in a town full of partisans. The word is “DOUBT.”

“I’d only been in Washington a few times, mainly for antiwar marches and pro-choice rallies,” she said. “But I’m interested in notions of power and control and love and money and death and pleasure and pain. And Richard [Koshalek, the director of the Hirshhorn] wanted me to exercise candor without trying to be ridiculously...I think I sometimes see things that are provocative for provocations’ sake.” (A rare admission for an artist—self-doubt.) “So I’m looking forward to bringing up these issues of belief, power and doubt.”

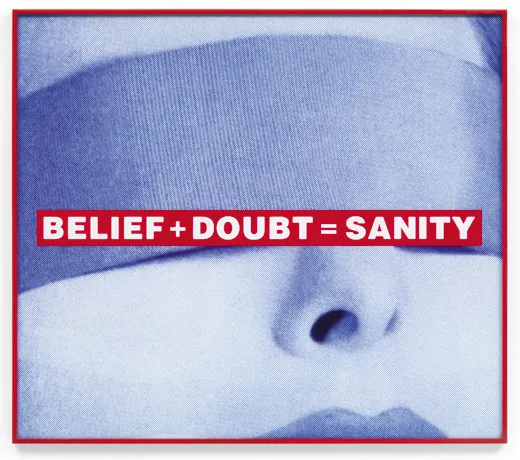

The official title she’s given her installation is Belief+Doubt. In an earlier work (pictured below), she had used the phrase Belief+Doubt=Sanity.

I asked her what had happened to “sanity.” Had she given up on it?

“You can say ‘clarity,’ you can say ‘wisdom,’” she replied, but if you look at the equation closely, adding doubt to belief is actually subtracting something from belief: blind certainty.

The conversation about doubt turned to agnosticism, the ultimate doubt.

She made clear there’s an important distinction between being an atheist and being an agnostic, as she is: Atheists don’t doubt! “Atheists have the ferociousness of true believers—which sort of undermines their position!” she said.

“In this country,” she added, “it’s easier to be a pedophile than an agnostic.”

Both sides—believer and atheist—depend on certainty to hold themselves together. A dynamic that also might explain the deadlock in politics in Washington: both sides refusing to admit the slightest doubt about their position, about their values, about the claim to have all the answers.

“Whose values?” is the Kruger extraction at the very summit of her Hirshhorn installation—and its most subversive question. With the absence of doubt, each side clings to its values, devaluing the other side’s values, making any cooperation an act of betrayal.

“Everybody makes this values claim,” she pointed out, “that their values are the only values. Doubt is almost grounds for arrest—and we’re still perilously close to that in many ways, you know.”

And so in its way the Hirshhorn installation may turn out to be genuinely subversive. Introducing doubt into polarized D.C. political culture could be like letting loose a mutation of the swine flu virus.

Let’s hope it’s contagious.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/ron-rosenbaum-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/ron-rosenbaum-240.jpg)