Black Like Me, 50 Years Later

John Howard Griffin gave readers an unflinching view of the Jim Crow South. How has his book held up?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Presence-Color-Line-John-Howard-Griffin-631.jpg)

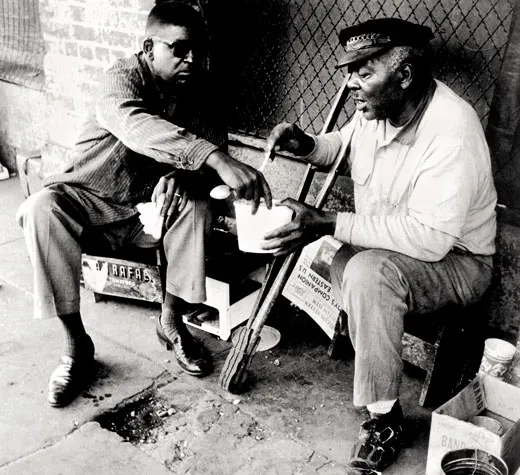

Late in 1959, on a sidewalk in New Orleans, a shoe-shine man suffered a sense of déjà vu. He was certain he’d shined these shoes before, and for a man about as tall and broad-shouldered. But that man had been white. This man was brown-skinned. Rag in hand, the shoeshine man said nothing until the hulking man spoke.

“Is there something familiar about these shoes?”

“Yeah, I been shining some for a white man—”

“A fellow named Griffin?”

“Yeah. Do you know him?”

“I am him.”

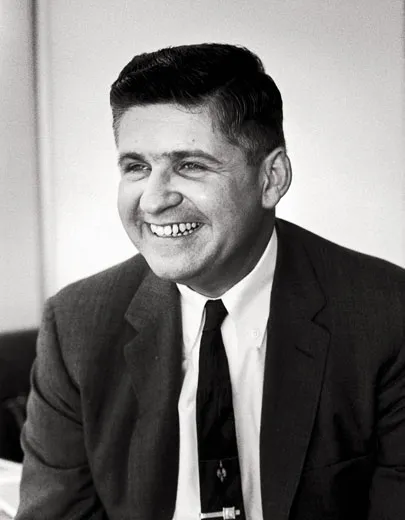

John Howard Griffin had embarked on a journey unlike any other. Many black authors had written about the hardship of living in the Jim Crow South. A few white writers had argued for integration. But Griffin, a novelist of extraordinary empathy rooted in his Catholic faith, had devised a daring experiment. To comprehend the lives of black people, he had darkened his skin to become black. As the civil rights movement tested various forms of civil disobedience, Griffin began a human odyssey through the South, from New Orleans to Atlanta.

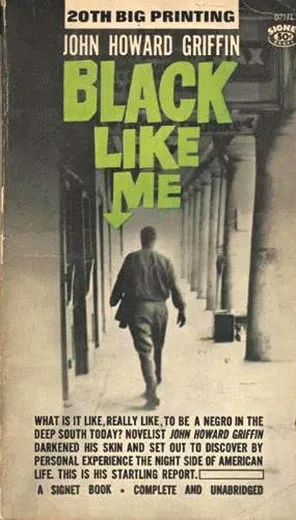

Fifty years ago this month, Griffin published a slim volume about his travels as a “black man.” He expected it to be “an obscure work of interest primarily to sociologists,” but Black Like Me, which told white Americans what they had long refused to believe, sold ten million copies and became a modern classic.

“Black Like Me disabused the idea that minorities were acting out of paranoia,” says Gerald Early, a black scholar at Washington University and editor of Lure and Loathing: Essays on Race, Identity, and the Ambivalence of Assimilation. “There was this idea that black people said certain things about racism, and one rather expected them to say these things. Griffin revealed that what they were saying was true. It took someone from outside coming in to do that. And what he went through gave the book a remarkable sincerity.”

A half century after its publication, Black Like Me retains its raw power. Still assigned in many high schools, it is condensed in online outlines and video reviews on YouTube. But does the book mean the same in the age of Obama as it did in the age of Jim Crow?

“Black Like Me remains important for several reasons,” says Robert Bonazzi, author of Man in the Mirror: John Howard Griffin and the Story of Black Like Me. “It’s a useful historical document about the segregated era, which is still shocking to younger readers. It’s also a truthful journal in which Griffin admits to his own racism, with which white readers can identify and perhaps begin to face their own denial of prejudice. Finally, it’s a well-written literary text that predates the ‘nonfiction novel’ of Mailer, Capote, Tom Wolfe and others.”

Griffin, however, has become the stuff of urban legend, rumored to have died of skin cancer caused by the treatments he used to darken his skin temporarily. Nearly forgotten is the remarkable man who crossed cultures, tested his faith and triumphed over physical setbacks that included blindness and paralysis. “Griffin was one of the most remarkable people I have ever encountered,” the writer Studs Terkel once said. “He was just one of those guys that comes along once or twice in a century and lifts the hearts of the rest of us.”

Born in Dallas in 1920, Griffin was raised in nearby Fort Worth. “We were given the destructive illusion that Negroes were somehow different,” he said. Yet his middle-class Christian parents taught him to treat the family’s black servants with paternalistic kindness. He would always recall the day his grandfather slapped him for using a common racial epithet of the era. “They’re people,” the old man told the boy. “Don’t you ever let me hear you call them [that] again.”

Griffin was gifted with perfect pitch and a photographic memory, but his most vital gift was curiosity. At 15, he earned entrance to a boarding school in France, where he was “delighted” to find black students in class but appalled to see them dining with white people in cafés. “I had simply accepted the ‘customs’ of my region, which said that black people could not eat in the same room with us,” Griffin later wrote. “It had never occurred to me to question it.”

Griffin was studying psychiatry in France when Hitler’s troops invaded Poland in 1939. Finding himself “in the presence of a terrible human tragedy,” he joined the French Resistance and helped smuggle Jewish children to England. When he told an informer of a plan to help a family escape, his name turned up on a Nazi death list. Fleeing just ahead of the Gestapo, Griffin returned to Texas in 1941 and enlisted in the Army Air Corps shortly after Pearl Harbor.

While working as a radio operator in the Pacific, he was sent on his own to the Solomon Islands to ensure natives’ loyalty to the American war effort. For a full year, Griffin studied tribal languages and adaptation to the jungle, but still assumed that “mine was a ‘superior’ culture.”

After getting blasted with shrapnel in an enemy air raid a few months before the end of the war, Griffin awoke in a hospital, seeing only shadows; eventually, he saw nothing. The experience was revealing. The blind, he wrote, “can only see the heart and intelligence of a man, and nothing in these things indicates in the slightest whether a man is white or black.” Blindness also forced Griffin to find new strengths and talents. Over the next decade, he converted to Catholicism, began giving lectures on Gregorian chants and music history, married and had the first of four children. He also published two novels based on his wartime experience. Then in 1955, spinal malaria paralyzed his legs.

Blind and paraplegic, Griffin had reason to be bitter, yet his deepening faith, based on his study of Thomas Aquinas and other theologians, focused on the sufferings of the downtrodden. After recovering from malaria, he was walking in his yard one afternoon when he saw a swirling redness. Within months, for reasons that were never explained, his sight was fully restored.

Across the South in the summer of 1959, drinking fountains, restaurants and lunch counters still carried signs reading, “Whites Only.” Most Americans saw civil rights as a “Southern problem,” but Griffin’s theological studies had convinced him that racism was a human problem. “If a white man became a Negro in the Deep South,” he wrote on the first page of Black Like Me, “what adjustments would he have to make?” Haunted by the idea, Griffin decided to cross the divide. “The only way I could see to bridge the gap between us,” he would write, “was to become a Negro.”

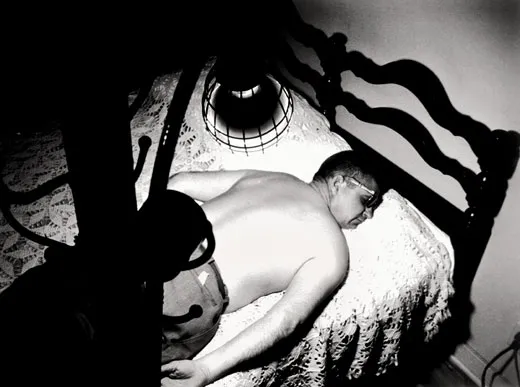

An acquaintance told Griffin the idea was crazy. (“You’ll get yourself killed fooling around down there.”) But his wife, Elizabeth, backed his plan. Soon Griffin was consulting a dermatologist, spending hours under sunlamps and taking a drug that was used to treat vitiligo, a disease that whitened patches of skin. As he grew darker day by day, Griffin used a stain to cover telltale spots, then shaved his head. Finally, his dermatologist shook his hand and said, “Now you go into oblivion.”

Oblivion proved worse than Griffin had imagined. Alone in New Orleans, he turned to a mirror. “In the flood of light against white tile, the face and shoulders of a stranger—a fierce, bald, very dark Negro—glared at me from the glass,” he would write. “He in no way resembled me. The transformation was total and shocking....I felt the beginnings of a great loneliness.”

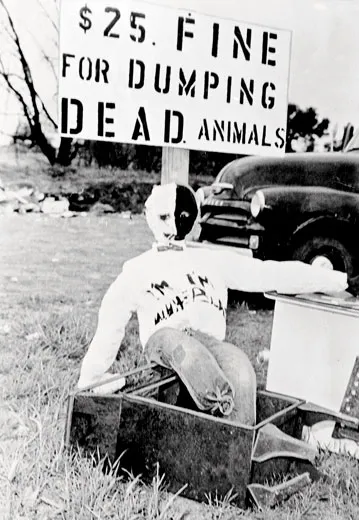

Stepping outside, Griffin began his “personal nightmare.” Whites avoided or scorned him. Applying for menial jobs, he met the ritual rudeness of Jim Crow. “We don’t want you people,” a foreman told him. “Don’t you understand that?” Threatened by strangers, followed by thugs, he heard again and again the racial slur for which he had been slapped as a boy. That word, he wrote, “leaps out with electric clarity. You always hear it, and always it stings.”

Carrying just $200 in traveler’s checks, Griffin took a bus to Hattiesburg, Mississippi, where a recent lynching had spread fear through the alleys and streets. Griffin holed up in a rented room and wrote of his overwhelming sense of alienation: “Hell could be no more lonely or hopeless.” He sought respite at a white friend’s home before resuming his experiment—“zigzagging,” he would call it, between two worlds. Sometimes passing whites offered him rides; he did not feel he could refuse. Astonished, he soon found many of them simply wanted to pepper him with questions about “Negro” sex life or make lurid boasts from “the swamps of their fantasy lives.” Griffin patiently disputed their stereotypes and noted their amazement that this Negro could “talk intelligently!” Yet nothing gnawed at Griffin so much as “the hate stare,” venomous glares that left him “sick at heart before such unmasked hatred.”

He roamed the South from Alabama to Atlanta, often staying with black families who took him in. He glimpsed black rage and self-loathing, as when a fellow bus passenger told him: “I hate us.” Whites repeatedly insisted blacks were “happy.” A few whites treated him with decency, including one who apologized for “the bad manners of my people.” After a month, Griffin could stand no more. “A little thing”—a near-fight when blacks refused to give up their seats to white women on a bus—sent Griffin scurrying into a “colored” restroom, where he scrubbed his fading skin until he could “pass” for white. He then took refuge in a monastery.

Before Griffin could publish reports on his experiment in Sepia magazine, which had helped bankroll his travels, word leaked out. In interviews with Time and CBS, he explained what he’d been up to without trying to insult Southern whites. He was subjected to what he called “a dirty bath” of hatred. Returning to his Texas hometown, he was hanged in effigy; his parents received threats on his life. Any day now, Griffin heard, a mob would come to castrate him. He sent his wife and children to Mexico, and his parents sold their property and went into exile too. Griffin remained behind to pack his studio, wondering, “Is tonight the night the shotgun blasts through the window?” He soon followed his family to Mexico, where he turned his Sepia articles into Black Like Me.

In October 1961, Black Like Me was published, to wide acclaim. The New York Times hailed it as an “essential document of contemporary American life.” Newsweek called it “piercing and memorable.” Its success—translated into 14 languages, made into a movie, included in high-school curriculums—turned Griffin into a white spokesman for black America, a role he found awkward.

“When Griffin was invited to troubled cities, he said exactly the same thing local black people had been saying,” notes Nell Irvin Painter, a black historian and the author of The History of White People. “But the powers that were could not hear the black people. Black speakers in America had little credibility until ‘yesterday.’ Some CNN correspondents who are black now get to comment on America, but that’s a very recent phenomenon.”

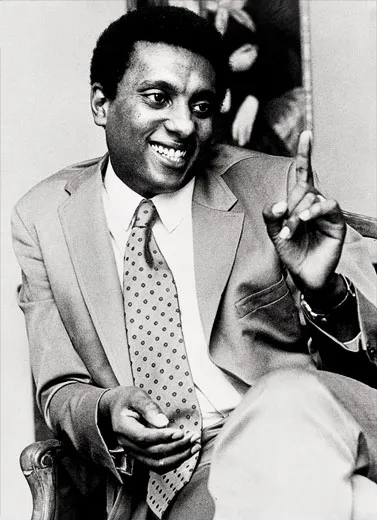

As the civil rights movement accelerated, Griffin gave more than a thousand lectures and befriended black spokesmen ranging from Dick Gregory to Martin Luther King Jr. Notorious throughout the South, he was trailed by cops and targeted by Ku Klux Klansmen, who brutally beat him one night on a dark road in 1964, leaving him for dead. By the late 1960s, however, the civil rights movement and rioting in Northern cities highlighted the national scale of racial injustice and overshadowed Griffin’s experiment in the South. Black Like Me, said activist Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture), “is an excellent book—for whites.” Griffin agreed; he eventually curtailed his lecturing on the book, finding it “absurd for a white man to presume to speak for black people when they have superlative voices of their own.”

Throughout the 1970s, Griffin struggled to move beyond Black Like Me. Having befriended Thomas Merton, he began a biography of the Trappist monk, even living in Merton’s cell after his death. Hatred could not penetrate his hermitage, but diabetes and heart trouble could. In 1972, osteomyelitis put him back in a wheelchair. He published a memoir urging racial harmony, but other works—about his blindness, about his hermitage days—would be published posthumously. He died in 1980, of heart failure. He was 60.

By then, the South was electing black mayors, congressmen and sheriffs. The gradual ascent of black political power has turned Black Like Me into an ugly snapshot of America’s past. Yet Gerald Early thinks the book might be even more relevant now than in the 1960s: “Because the book talks about events that took place some 50 years ago, it might get people to talk about the racial issues of today in a calmer way, with a richer meaning because of the historical perspective.”

Nell Irvin Painter notes that while the country is no longer as segregated as it was a half century ago, “segregation created the ‘twoness’ Griffin and W.E.B. DuBois wrote about. That twoness and the sense of holding it all together with your daunted strength and being exhausted—that’s still very telling.”

Fifty years after its publication, Black Like Me remains a remarkable document. John Howard Griffin changed more than the color of his skin. He helped change the way America saw itself.

Bruce Watson is the author of several books, including Freedom Summer.