A Brief History of Pierre L’Enfant and Washington, D.C.

How one Frenchman’s vision became our capital city

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/brief-lenfant-631.jpg)

Today's Washington, D.C. owes much of its unique design to Pierre Charles L'Enfant, who came to America from France to fight in the Revolutionary War and rose from obscurity to become a trusted city planner for George Washington. L'Enfant designed the city from scratch, envisioning a grand capital of wide avenues, public squares and inspiring buildings in what was then a district of hills, forests, marshes and plantations.

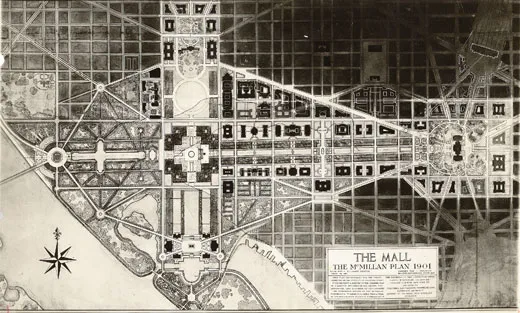

The centerpiece of L'Enfant's plan was a great "public walk." Today's National Mall is a wide, straight strip of grass and trees that stretches for two miles, from Capitol Hill to the Potomac River. Smithsonian museums flank both sides and war memorials are embedded among the famous monuments to Lincoln, Washington and Jefferson.

L'Enfant and the Capital

Washington D.C. was established in 1790 when an act of Congress authorized a federal district along the Potomac River, a location offering an easy route to the western frontier (via the Potomac and Ohio River valleys) and conveniently situated between the northern and southern states.

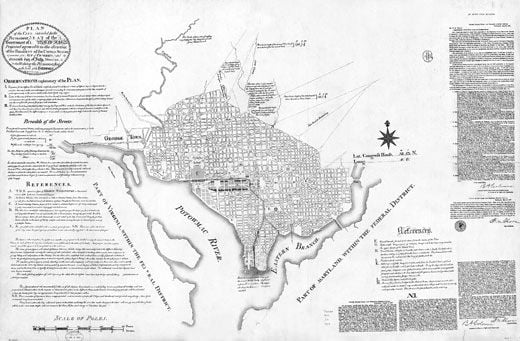

President Washington chose an area of land measuring 100 square miles where the Eastern Branch (today's Anacostia River) met the Potomac just north of Mount Vernon, his Virginia home. The site already contained the lively port towns of Alexandria and Georgetown, but the new nation needed a federal center with space dedicated to government buildings.

Washington asked L'Enfant, by then an established architect, to survey the area and recommend locations for buildings and streets. The Frenchman arrived in Georgetown on a rainy night in March 1791 and immediately got to work. "He had this rolling landscape at the confluence of two great rivers," said Judy Scott Feldman, chairwoman of the National Coalition to Save Our Mall. "He essentially had a clean slate on which to design the city." Inspired by the topography, L'Enfant went beyond a simple survey and envisioned a city where important buildings would occupy strategic places based on changes in elevation and the contours of waterways.

While Thomas Jefferson had already sketched out a small and simple federal town, L'Enfant reported back to the president with a much more ambitious plan. For many, the thought of a metropolis rising out of a rural area seemed impractical for a fledgling nation, but L'Enfant won over an important ally. "Everything he said, a lot of people would have found it crazy back then, but Washington didn't," says L'Enfant biographer Scott Berg.

His design was based on European models translated to American ideals. "The entire city was built around the idea that every citizen was equally important," Berg says. "The Mall was designed as open to all comers, which would have been unheard of in France. It's a very sort of egalitarian idea."

L'Enfant placed Congress on a high point with a commanding view of the Potomac, instead of reserving the grandest spot for the leader's palace as was customary in Europe. Capitol Hill became the center of the city from which diagonal avenues named after the states radiated, cutting across a grid street system. These wide boulevards allowed for easy transportation across town and offered views of important buildings and common squares from great distances. Public squares and parks were evenly dispersed at intersections.

Pennsylvania Avenue stretched a mile west from the Capitol to the White House, and its use by officials ensured rapid development for the points in between. For the rural area to become a real city, L'Enfant knew it was crucial to incorporate planning strategies encouraging construction. But his refusal to compromise led to frequent clashes that eventually cost him his position.

City commissioners who were concerned with funding the project and appeasing the District's wealthy landowners didn't share L'Enfant's vision. The planner irked the commissioners when he demolished a powerful resident's house to make way for an important avenue and when he delayed producing a map for the sale of city lots (fearing real estate speculators would buy up land and leave the city vacant).

Eventually, the city's surveyor, Andrew Ellicott, produced an engraved map that provided details for lot sales. It was very similar to L'Enfant's plan (with practical changes suggested by officials), but the Frenchman got no credit for it. L'Enfant, now furious, resigned at the urging of Thomas Jefferson. When L'Enfant died in 1825 he had never received payment for his work on the capital and the city was still a backwater (due partly to L'Enfant's rejected development and funding proposals).

Through the 1800s to the McMillan Commission

A century after L'Enfant conceived an elegant capital, Washington was still far from complete.

In the 1800s, cows grazed on the Mall, which was then an irregularly shaped, tree-covered park with winding paths. Trains passing through a railroad station on the Mall interrupted debate in Congress. Visitors ridiculed the city for its idealistic pretensions in a bumpkin setting and there was even talk after the Civil War of moving the capital to Philadelphia or the Midwest.

In 1901, the Senate formed the McMillan Commission, a team of architects and planners who updated the capital based largely on L'Enfant's original framework. They planned an extensive park system, and the Mall was cleared and straightened. Reclaimed land dredged from the river expanded the park to the west and south, making room for the Lincoln and Jefferson memorials. The Commission's work finally created the famous green center and plentiful monuments of today's Washington.

L'Enfant and Washington Today

Some of L'Enfant's plans, including a huge waterfall cascading down Capitol Hill, were never realized. But the National Mall has been a great success, used for everything from picnics to protests. "The American people really took to the Mall in the 20th century and turned it into this great civic stage," Feldman says. "That was something that Pierre L'Enfant never envisioned ... a place for us to speak to our national leaders in the spotlight." It has become so popular that officials say it is "terribly overused," as evidenced by worn grass and bare patches of earth.

John Cogbill, chairman of the National Capital Planning Commission which oversees development in the city, says the Commission strives to fulfill L'Enfant's original vision while meeting the demands of a growing region. "We take [L'Enfant's plan] into account for virtually everything we do," he says. "I think he would be pleasantly surprised if he could see the city today. I don't think any city in the world can say that the plan has been followed so carefully as it has been in Washington."

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/brian.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/brian.png)