Can Bullets Be Beautiful?

Photographer Sabine Pearlman exposes the surprisingly delicate innards of rounds of ammunition

Photographer Sabine Pearlman grew up in a place where weapons have a very distinct connotation: Austria.

"The trauma of World War II still lingers in the collective conscience," she says. "So my perception of weapons and warfare has always been a very negative one."

In her early twenties, she was held up at gunpoint, further cementing her anti-gun perspective. Then, ten years ago, she moved to a place with a very different conversation surrounding weapons: the U.S.

"The right to keep and bear arms is highly valued and widely practiced among a large portion of society," she says. One of the main motivations behind her recent project AMMO—an exploration of rounds of ammunition, sliced cleanly in half—was catharsis. "It was a first step to conquer my own discomfort with the subject matter."

For the project, Pearlman visited a World War II-era bunker owned by a Swiss munitions specialist and collector who owns more than 900 pieces of historical pieces of ammunition. Among the items on display were a mix of pre-World War II-era and modern cartridges that he'd cut in half. He and Pearlman used putty to affix the bottoms of the cartridges to pieces of cardboard, then carefully carried them over to a spot where she'd set up lights for the photo shoot, taking care to avoid dumping out the tightly packed gunpowder when they were moved.

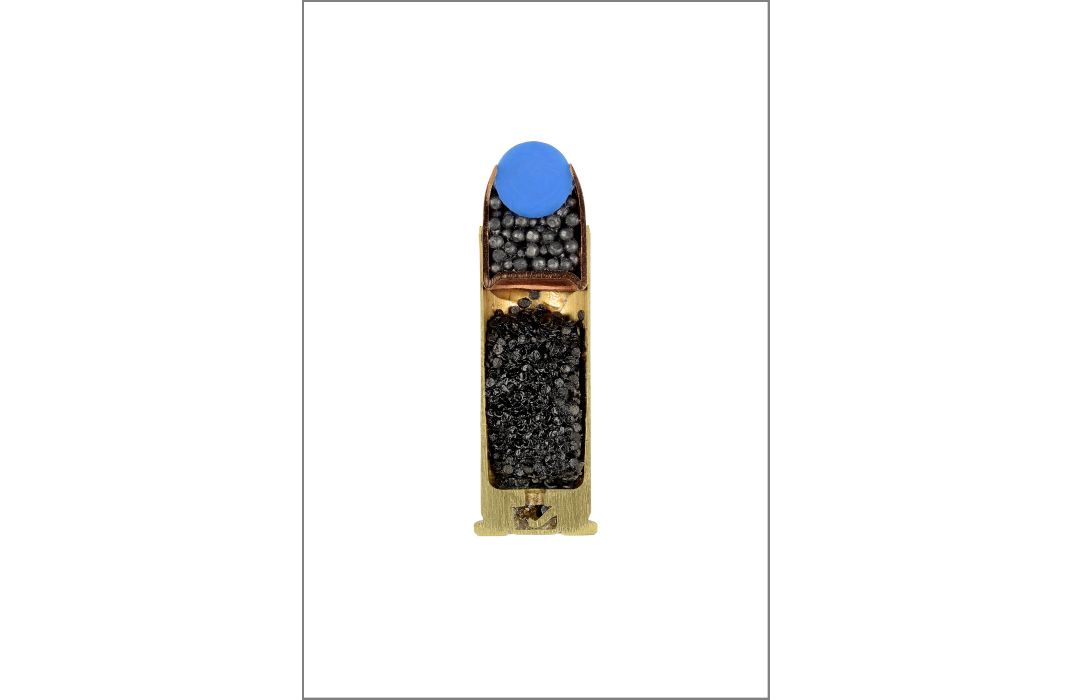

The result is a clinical snapshot of the anatomy of the projectiles. The cross-sections reveal how, although weapons technology has evolved over time, each round features the same basic construction: a bullet (the projectile at the top), a small supply of propellant (usually gunpowder) and a primer at the very bottom. When a gun's trigger is pulled, it sends a metal firing pin into the primer, which acts like a fuse, igniting the propellant. As the propellant burns, it gives off large quantities of gas, pushing the bullet out of the gun's barrel at extremely high speeds.

This chain reaction was designed with death in mind. But for such fundamentally lethal objects, Pearlman found something surprising about the cartridges—their inner delicacy and beauty. "The first time I saw a cross-section it sort of blew my mind. Never before had I considered a cartridge to be a beautiful object, yet there it was in all its stunning intricacy," she says says. "The juxtaposition of beauty and danger triggered my curiosity."

Since putting the works on display—they're currently part of an exhibition at Wall Space Gallery in Santa Barbara—Pearlman has been intrigued to see how many visitors admire the works without realizing that their abstracted, highly detailed subjects are in fact rounds of ammunition. "Some people see coffee grinders, surfboards, skateboards, cathedrals, lipstick, pralines, dildos or gum ball machines," she says. "Some viewers experience a sense of guilt when finding the images beautiful after discovering what they are, yet they’re still enchanted."

This strange sense of enchantment, Pearlman thinks, comes from bringing the hidden innards of a deadly object out into the open for the first time. "We get to see something that’s usually invisible to us. The images exude a latent danger," she says. "Much like Snow White’s apple in the Brothers’ Grimm fairy tale, AMMO represents themes of intrigue and tragedy, good and evil, beauty and horror, and allows us to reflect on our most inner fears and our highest hopes."

Sabine Pearlman's AMMO series is on display at Wall Space Gallery in Santa Barbara until March 30. The photos are also available as limited edition fine art prints.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)