Decoding the Range: The Secret Language of Cattle Branding

Venture into the highly regulated and fascinating world of bovine pyroglyphics

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20130430111035cattle-branding-locations-web.jpg)

To the untrained eye, cattle brands, those unique markings seared into animals’ hides with a hot iron, might just seem like idiosyncratic logos or trademarks designed to clearly and simply indicate ownership. However, unlike the graphic logos and trademarked images of popular commercial brands, they must comply with a rigorous set of standards and are developed using a specific language ruled by its own unique syntax and morphology.Livestock branding dates back to 2700 BC, evidenced by Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics. Ancient Romans are said to have used hot iron brands as an element of magic. But brands are most famously associated with the cowboys and cattle drives of the Old West, when brands were used to identify a cow’s owner, protect cattle from rustlers (cattle thieves), and to separate them when it came time to drive to market (or rail yards or stock yards).

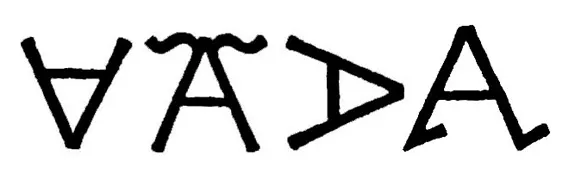

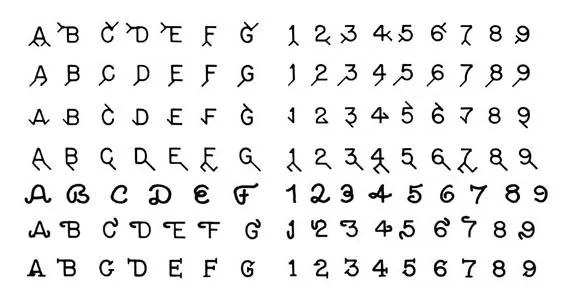

At its most basic, a cattle brand is composed of a few simple letters and numbers, possibly in combination with a basic shape or symbols like a line, circle, heart, arc, or diamond. But these characters can also be embellished with serif-like flourishes to create myriad “pyroglyphics.” For example, such serifs might include extraneous “wings” or “feet” added to a letter or number. Each character can also be rotated or reversed. Every addition and variation results in a unique character that is named accordingly. The letters with “wings” for example, are described as “flying” while those with “feet” are, you guessed it, “walking.” An upside-down characters is “crazy” while a 90-degree rotation makes a character “lazy.” These colorful designations aren’t just cute nicknames used to identify the characters, but are actually a part of the name, a spoken part of the brand language, which like most western languages is read from left to right, top to bottom and, perhaps unique to brands, outside to inside.

The vast array of combinations made possible by these characters and variations ensures that unique and identifiable brands can be created –hopefully without repetition– using only limited formal language. And sometimes they could even be used to make a joke:

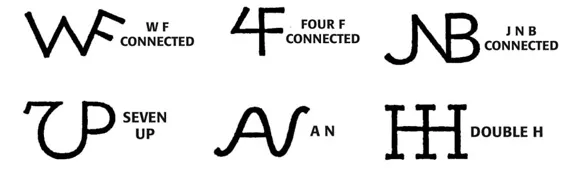

Serifs and rotations are just two of the primary ways brand letters can be modified. Multiple symbols may be joined together forming a type of ligature – a term used in typography to describe a single character representing two or more letters, such as æ. Some of these ligature brands are read as “connected” while others are given unique identifiers:

When it comes to getting your brand approved by the authorities, location is as important as design. The reason? The same brand can be registered in the same country as long as its located on a different part of the animal. The following two brands, for example, are considered distinct markings:

Brands are registered like trademarks or copyrights and are monitored, taxed and regulated. So if an owner failed to pay the brand tax, the brand could no longer be offered as “valid prima facie evidence of ownership.” Brands were, and continue to be, a critical element of the cattle industry unless –bonus fun fact!– you happen to have been 19th century Texas politician and rancher Samuel A. Maverick, who refused to brand his cattle and consequently saw his own surname immortalized as a brand for those independent few who refuse to follow the precepts of social order.

Today, the most successful trademarks and brand identities are the simplest and easiest to identify. Think of Nike’s swoosh or McDonald’s golden arches. The same is true for cattle brands. Not only is it easier to read a simple brand, but its less painful for the livestock. However, it can’t be too simple because the brand itself also serves as a means to combat theft and fraud, in much the same way that the swoosh is also an indicator of authenticity. Cattle rustlers would sometimes use a hot iron to alter brands into a similar graphic, then claim the cow as their own – its like a failing middle school student changing an “F” on his grade card to a “B” with a few pen marks so his parents don’t get upset. Although the phrase “cattle rustler” conjures romantic images of the Old West, it is still a very real problem for today’s ranchers. In fact, the U.S. is currently experience something of a rustling renaissance. Consequently, there’s also something of a branding revival. Despite the invention of GPS tagging, DNA testing (yes, for cattle), and other preventative measures, branding is still the top preventative measure to combat cattle theft. Carl Bennett, director of the Louisiana Livestock Brand Commission recently told USA Today that ”We have yet to find a system that can replace a hot brand on a cow. There’s nothing in modern society that’s more sure.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jimmy-Stamp-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jimmy-Stamp-240.jpg)