Designing Democracy Around a Ditch

How a ditch irrigation system in the arid Southwest became the backbone of local democracy

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20120514123007drylandsstudents-small.jpg)

![]() Read Part I, Part II, Part III, Part IV, Part V and Part VI of our series on water scarcity.

Read Part I, Part II, Part III, Part IV, Part V and Part VI of our series on water scarcity.

While most people understand climate change in the abstract, few consider the extent to which our existing infrastructure and land use were shaped by—and depend upon—specific climatic conditions that are quickly fading away. “The majority of our water comes from snow,” says architect Peter Arnold, referring to the water supply of the American west, “But that regime is changing. It’s going to come less from snow and more from storms and rain, and we’re not designed as a culture, nor do we have the infrastructure available yet, to fully take advantage of it coming in the form of rain.”

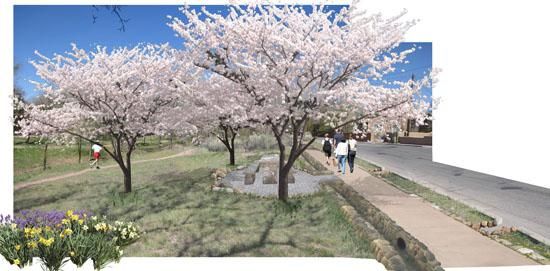

Each year, Arnold and his wife and architectural studio partner, Hadley, take their students away from their homebase at Woodbury University’s Arid Lands Institute in Los Angeles, and travel to northern New Mexico, where they work in a vast outdoor classroom known as the Lower Embudo Valley. In this region, water management technologies and practices are still in use that were developed many centuries ago by the Pueblo Indians, and have roots dating back even further to Moorish culture in Spain.

At the center of the water management tradition here is a ditch, called an acequia—a word that refers not only to the physical trench in the ground, but also to an entire system of community governance that ensures each member of a community has access to adequate water for irrigation and household needs. “You don’t just have a ditch, you belong to an acequia,” explains Hadley Arnold, “which is a small coop of farmers who share the ditch and who govern themselves and their use of water in a collaborative dialogue according to rules that were established about 1000 years ago in Spain. It’s a perfect example of ‘water democracy.’”

The physical feature of the acequia is built by diverting water from a river—in this case the Rio Embudo and the Rio Grande—into a parallel channel that runs with gravity, using no pumps. The acequias slow the flow rate of the water, allowing farmers (and the land) to capture it before it becomes runoff or flood. The ditch can be opened at intermittent points along its length to allow irrigation to reach crops. That distribution process is determined by a commissioner—or mayordomo—who assesses how much water is available on any given day, and permits each farmer a certain period of time during which the acequia can be opened onto their land.

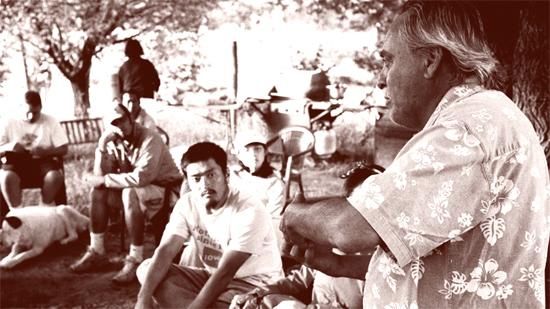

“The acequia is its own entity and it’s a subdivision of local government,” explains Estevan Arellano, a writer, historian, and former mayordomo. Arellano spends much of his time advocating for and teaching about the acequias, working to maintain the ditches themselves and the social structure around them, even as modern life seems to draw people away from land-based livelihoods.

Arellano’s presence in this conversation is impossible to overlook. When I called up landscape architect Kenneth Francis, a former student from Harvard’s Graduate School of Design who had researched the acequias in school, he told me Arellano had been his guide several years ago as he walked the ditches and tried to learn how the model could be adapted for urban water management and landscape design.

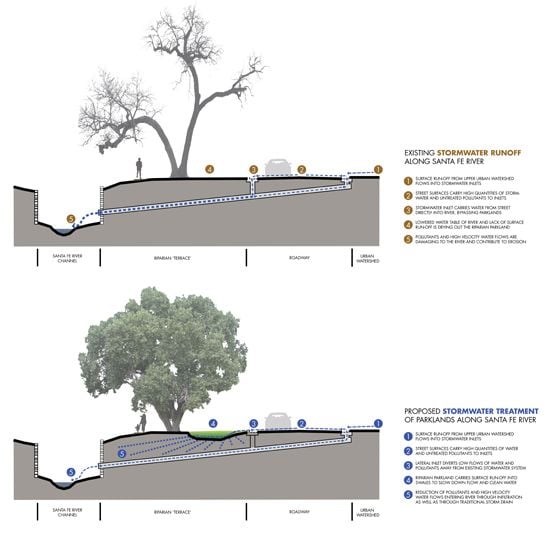

Having graduated and established a practice, Surroundings Studio, in Santa Fe, Francis is now taking the lessons he learned while studying the acequias into client projects. Currently, his firm is working with the city of Santa Fe to create what Francis calls “stormwater acequias“—a green infrastructure system that provides conduits for heavy rain to flow off city streets and into the ground, hydrating a corridor of trees that line the urban parkway.

“Right now rainwater gets point-sourced right out into the river,” Francis explains, “It creates a strong erosive condition and also concentrates pollutants in one area. We started to create a wider distribution network where water would infiltrate under the sidewalk and into these linear acequias.” Built using scoria rock—a pumice-like stone with micropores throughout—the urban acequias are able to hold water for long periods of time, hydrating and restoring the riparian zone within the city. Francis’s project involves planting fruit trees along the corridor where orchards existed long ago, reintroducing heritage varieties that will thrive on runoff from impermeable surfaces.

But what happens to all the other aspects of the acequia in this case—the social networks and cooperative governance that form around the waterways? Francis says that park maintenance staff will be in charge of maintaining the stormwater acequias, so the design doesn’t require the community’s hands-on, cooperative management to the extent of its rural counterpart. “Acequias are one of our tools,” he says, “It’s more of a contemporary cultural expression of a system that brings water into an area that doesn’t have it. It’s interpreted not just to water an orchard, but also to take water off the street and help clean it.”

Francis’s application of the traditional water management system in an urban context is one example of what Hadley and Peter Arnold’s students may do with the knowledge they gain during their immersion in the Embudo Valley. This is one of the few places, the Arnolds say, where a young landscape architect or urban planner can see a living example of a low-carbon, low-energy-demand innovation that can adapt (and has) to dry and volatile conditions over time. “The students are asking, How do you use land differently if your snowpack is dwindling and your land isn’t supporting things the same? How do you plant differently to harvest some of the rain? How does the settlement pattern change if you recognize that arroyos aren’t just a flood problem but also a possibility for banking water?”

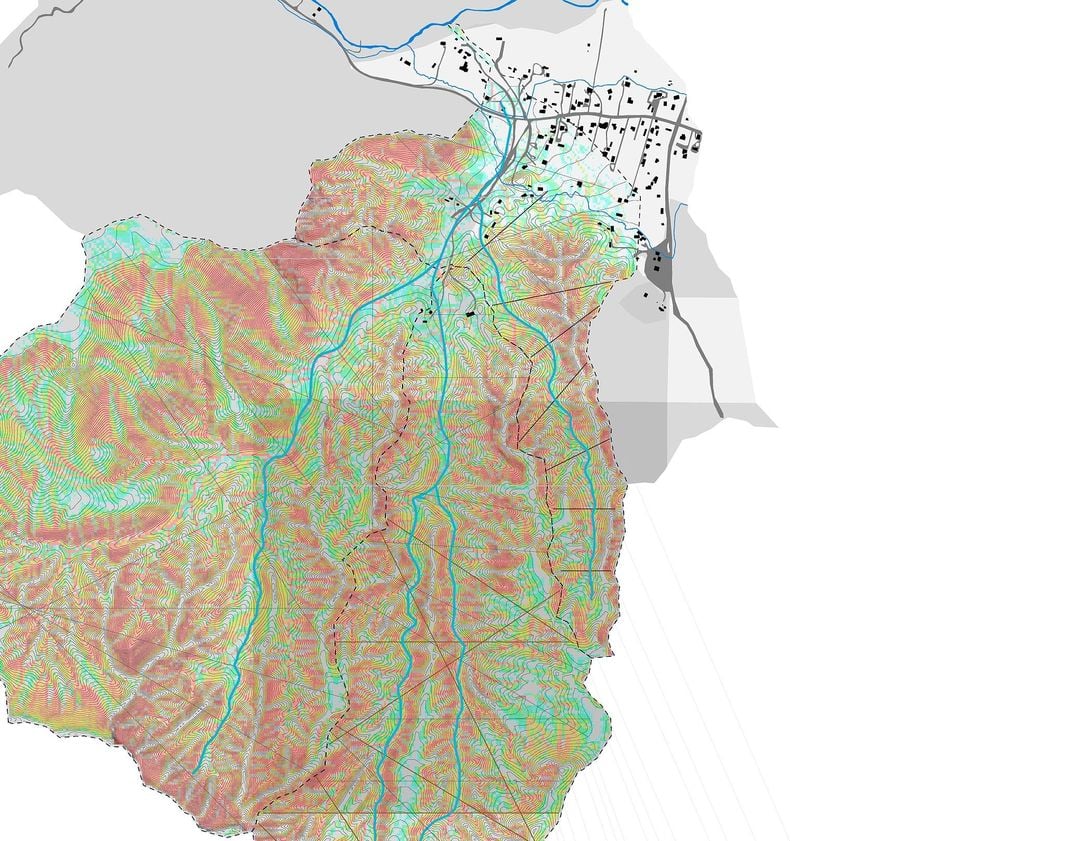

There’s no question the Arnolds’ students learn from the acequias, but Peter points out that they also contribute to the community when they visit, bringing mapping, modeling, GIS and land use planning skills to bear to support and strengthen the existing systems. ”If there’s going to be a technological approach to climate change mitigation in terms of understanding how to budget our water,” says Peter, “it has to be a fusion of design strategies, leveraging policy and scientific analysis into to make spaces more dynamic, infrastructure more visible, and public space more robust.”

Read Part I, Part II, Part III, Part IV, Part V and Part VI of our series on water scarcity.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/sarah-rich-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/sarah-rich-240.jpg)