Egypt’s Murals Are More Than Just Art, They Are a Form of Revolution

Cairo’s artists have turned their city’s walls into a vast social network

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Phenomenon-Writings-on-the-Wall-Egypt-631.jpg)

Forgetfulness is the national disease of Egypt. But a new generation, born from the revolution that erupted during the Arab Spring, refuses to forget and insists on recording everything and anything. When I co-founded the April 6 Youth Movement to promote peaceful political activism, I believed that the most effective tools for documenting our struggle were social networks, such as Facebook and Twitter. (See Ron Rosenbaum’s profile of Mona Eltahawy for an inside story of Egypt’s revolution.) Yet, I’ve come to learn that there will always be new tools—graffiti is one of them.

Graffiti was a rare sight until two years ago, when artists began documenting the crimes of our regime. The artists—some acting on their own, others as part of an artistic collective—remind those who take political stands that nothing escapes the eyes and ears of our people. They cover their concrete canvases with portraits of activists like Ahmed Harara, who lost both his eyes during protests to see his country free.

The graffiti has become a self-perpetuating movement. The images provoke the government, which responds with acts of cruelty that only increase the resolve of the artists. Much of the street art is covered over or defaced after it is created. That’s what prompted Soraya Morayef, a Cairo-based journalist, to photograph and document the images on her blog, “Suzee in the City.” She is an art critic as astute as those who survey the genteel galleries in New York and Paris.

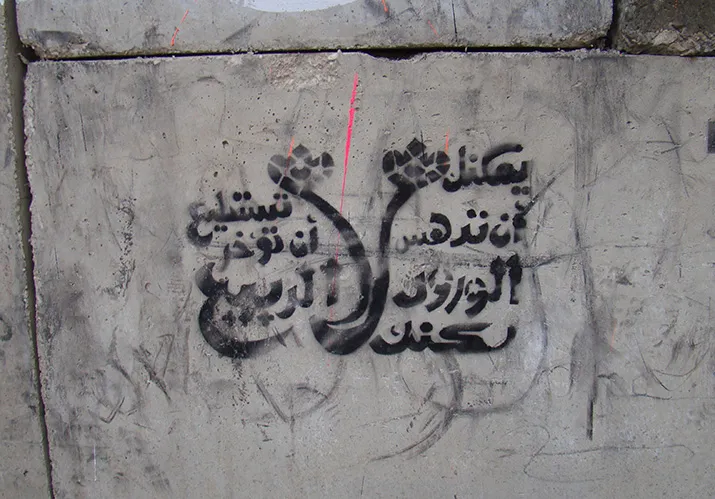

“There are so many artists and styles,” Morayef says. “You can tell when someone has been influenced by Banksy or hip-hop fonts, but there are also a lot of individual styles using Arabic calligraphy and that have been inspired by Egyptian pop culture. There is Alaa Awad, who paints pharaonic temples and murals but with a modern twist to them. Then you have El Zeft and Nazeer, who plan their graffiti like social campaigns, where they pick a strategic location and write about it on social media and make short videos.”

Some artists paint freehand murals; others use stencils and spray cans. “I don’t know all the graffiti artists in Egypt,” Morayef adds, “but the ones I have met are courteous, intellectual minds that have a lot more to say than just making art on a wall.”

Her description is very much on my mind when I meet Ahmed Naguib, 22, a student at Cairo University’s Faculty of Commerce. Naguib tells me that he’s loved drawing since he was very young and didn’t hesitate joining a revolutionary art collective. He drew his first graffiti in July 2011, protesting the brutal actions of the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces—which temporarily assumed power after Hosni Mubarak was deposed, and still retains considerable influence under the presidency of Mohamed Morsi. “People singing revolutionary slogans come and go,” says Naguib, “but the graffiti remains and keeps our spirits alive.”

For me, the graffiti represent the creativity of people to develop new tools for protest and dialogue that are stronger and more permanent than the tyranny of their rulers. The artists have transformed the city’s walls into a political rally that will never end as long as noisy Cairo remains.