Hemingway in Love

In a new memoir, one of Hemingway’s closest friends reveals how the great writer grappled with the love affair that changed his life and shaped his art

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/01/0d/010dce22-9685-4c38-8783-c0bd770533a7/oct2015_e01_hemingway.jpg)

In the spring of 1948, I was dispatched to Havana on the ridiculous mission of asking Ernest Hemingway to write an article on “The Future of Literature.” I was with Cosmopolitan, then a literary magazine, before its defoliation by Helen Gurley Brown, and the editor was planning an issue on the future of everything: Frank Lloyd Wright on architecture, Henry Ford II on automobiles, Picasso on art, and, as I said, Hemingway on literature.

Of course, no writer knows the future of literature beyond what he’ll write the next morning. Checking into the Hotel Nacional, I took the coward’s way out and wrote Hemingway a note, asking him to please send me a brief refusal. Instead of a note, I received a phone call the next morning from Hemingway, who proposed five o’clock drinks at his favorite Havana bar, the Floridita. He arrived precisely on time, an overpowering presence, not in height, for he was only an inch or so over six feet, but in impact. Everyone in the place responded to his entrance.

The two frozen daiquiris the barman placed in front of us were in conical glasses big enough to hold long-stemmed roses.

“Papa Dobles,” Ernest said, “the ultimate achievement of the daiquiri maker’s art.” He conversed with insight and rough humor about famous writers, the Brooklyn Dodgers, who held spring training in Cuba the previous year, actors, prizefighters, Hollywood phonies, fish, politicians, everything but “The Future of Literature.”

He left abruptly after our fourth or fifth daiquiri—I lost count. When I got back to the hotel, despite the unsteadiness of my pen, I was able to make some notes of our conversation on a sheet of hotel stationery. For all the time I knew him, I made a habit of scribbling entries about what had been said and done on any given day. Later on, I augmented these notes with conversations recorded on my Midgetape, a minuscule device the size of my hand, whose tapes allowed 90 minutes of recording time. Ernest and I sometimes corresponded by using them. Although the tapes disintegrated soon after use, I found them helpful.

Ernest and his wife, Mary, and I stayed in touch for the next eight months. That was the beginning of our friendship.

Over the following years, while we traveled, he relived the agony of that period in Paris when, married to his first wife, Hadley Richardson, he was writing The Sun Also Rises and at the same time enduring the harrowing experience of being in love with two women simultaneously, an experience that would haunt him to his grave.

I have lived with Ernest’s personal story for a long time. This is not buried memory dredged up. The story he recounted was entrusted to me with a purpose. I have held that story in trust for these many years, and now I feel it is my fiduciary obligation to Ernest finally to release it from my memory.

**********

It was on the morning of January 25, 1954, that word flashed around the world that Ernest and Mary had been killed in a plane crash in dense jungle near Murchison Falls in Uganda, setting off universal mourning and obituaries. But news of the tragedy was soon superseded by a report that Ernest had suddenly, miraculously, emerged from the jungle at Butiaba carrying a bunch of bananas and a bottle of Gordon’s gin. A few hours later, a de Havilland Rapide, a 1930s-era biplane, was sent to the crash site to fly Ernest and Mary back to their base in Kenya, but the de Havilland crashed on takeoff and burst into flames; it was that second crash that left its mark on Ernest.

Not long after, when I got to his corner room at the Gritti Palace hotel in Venice, Ernest was sitting in a chair by the window, tennis visor in place, reading his worldwide obituaries from a stack of newspapers on the desk beside him. “Right arm and shoulder dislocated,” he said, “ruptured kidney, back gone to hell, face, belly, hand, especially hand, all charred by the de Havilland fire. Lungs scalded by smoke.”

Ernest had ordered a bottle of Valpolicella Superiore, which he told the waiter to pour without waiting for the bottle to breathe. “Italian reds don’t need oxygen,” he said. “I got that bit of Bacchanalian wisdom from Fitzgerald.”

I said, “You got a lot from Fitzgerald, didn’t you? ”

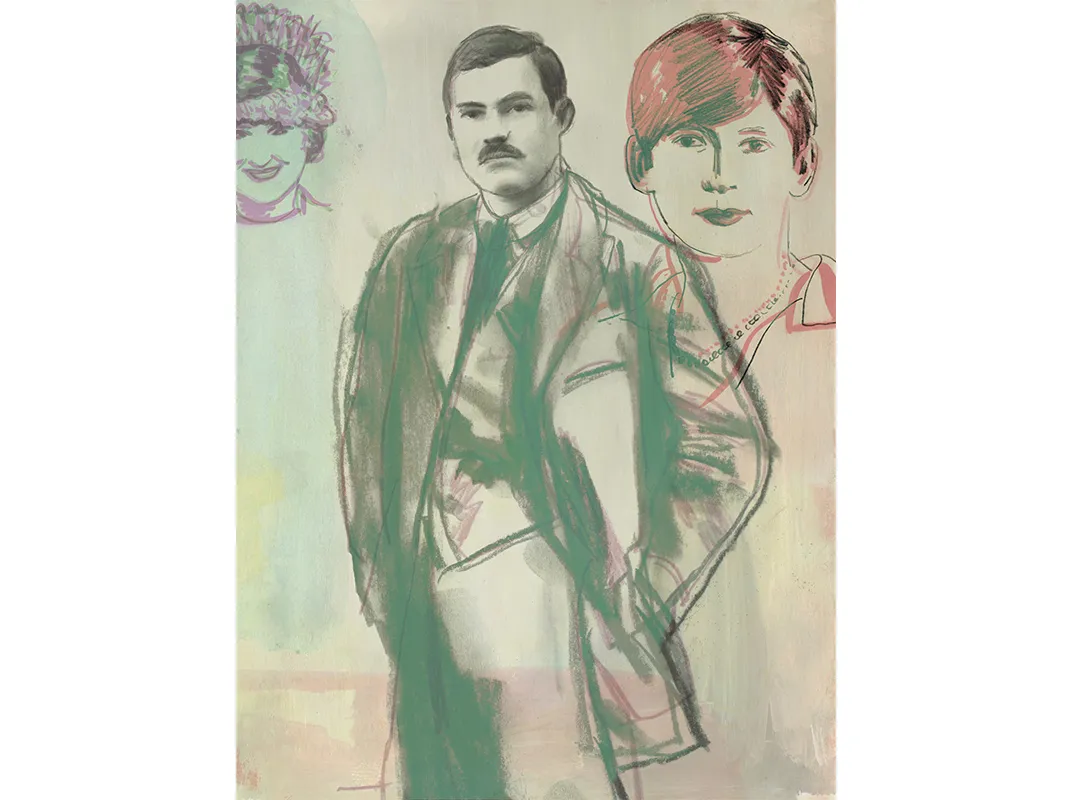

“Got and gave,” Ernest said. “Met him first in Paris at the Dingo Bar. The Fitzgeralds sometimes invited us to dinner, and on one occasion two sisters, Pauline and Ginny Pfeiffer.”

“So that’s how you met Pauline? What was your take on her? ”

“First impression? Small, flat-chested, not nearly as attractive as her sister. Pauline had recently come to Paris to work at Vogue magazine, and she looked like she’d just stepped out of its pages. Up-to-date fashion. Close-cropped hair like a boy’s, à la mode back then, short; fringed dress, loops of pearls, costume jewelry, rouged, bright red lips.

“I never gave Pauline another thought after that dinner. Hadley was the only woman who mattered in my life, her full body and full breasts, hair long to her shoulders, long-sleeved dresses at her ankles, little or no jewelry or makeup. I adored her looks and the feel of her in bed, and that’s how it was. She lived her life loving the things I loved: skiing in Austria, picnics on the infield at the Auteuil races, staying up all night at the bicycle races at the Vélodrome, fortified with sandwiches and a thermos of coffee, trips to alpine villages to watch the Tour de France, fishing in the Irati, the bullfights in Madrid and Pamplona, hiking in the Black Forest.

“Occasionally, Pauline and Ginny would come by my workplace at the end of a day, that little bare room I had rented on the fifth floor, sans heat, sans lift, sans most everything, in the old shabby hotel on rue Mouffetard. They’d corral me for drinks at a nearby café, bringing good humor and wit and liveliness to what had been a frustrating, unproductive day. After a time, Ginny didn’t come anymore and Pauline came alone, looking up-to-the-minute chic, cheerful and exuding admiration, which, of course, after a tough day felt good.

“She had the ‘I get what I want’ hubris of a very rich girl who won’t be denied. The Pfeiffer clan owned the town of Piggott, Arkansas. Pauline’s old man owned a chain of drugstores and God knows what else—maybe all of Arkansas.

“Back then, to be honest, I probably liked it—poverty’s a disease that’s cured by the medicine of money. I guess I liked the way she spent it—designer clothes, taxis, restaurants. Later on, when reality got to me, I saw the rich for what they were: a goddamn blight like the fungus that kills tomatoes. I set the record straight in Snows of Kilimanjaro, but Harry, who’s laid up with a gangrenous leg, is too far gone by then and he dies without forgiving the rich. I think I still feel the way Harry felt about the rich in the story. Always will.”

Ernest asked if I had been to the feria in Pamplona, the annual bullfight festival that honored their patron saint. I said I hadn’t. “I started to write soon after we left Pamplona, and for the next five weeks it overwhelmed me. That fever was an out-of-control brush fire that swept me into Pauline’s maw. She’d have me for a drink in her attractive apartment on rue Picot, and that started it.

“I first called the book Fiesta, later on Sun Also Rises. Over those five weeks, I wrote it in various places, promising myself that when I returned to Paris, I’d avoid Pauline, but the fever of writing and rewriting opened me up to her.”

He refilled his wineglass. I passed.

“You ever loved two women at the same time ? ”

I said I hadn’t.

“Lucky boy,” he said.

“Fitzgerald could see it coming right from the start,” Ernest went on. “He said, ‘You are being set up by a femme fatale. When she first arrived in Paris, word was out that she was shopping for a husband. She wants you for herself, and she’ll do anything to get you.’ I leveled with him and confessed I loved both of them.

“All I see after a really tough day writing, there’re two women waiting for me, giving me their attention, caring about me, women both appealing, but in different ways. Told Scott I liked having them around. Stimulating, fires me up.

“Scott said I was a sad son of a bitch who didn’t know a damn thing about women. He gripped my arm and pulled me toward him. Raised his voice. ‘Get rid of her! Now! Right here! It’s a three-alarm fire! Now’s the time! Tell her!’

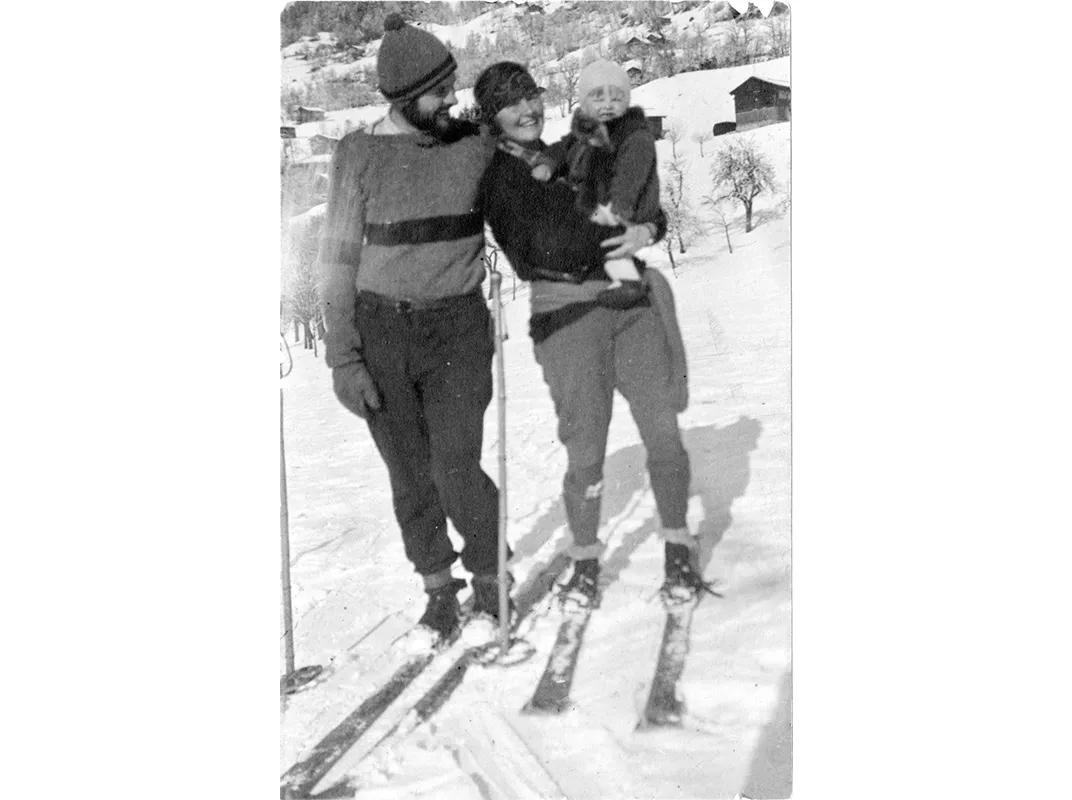

“I truly loved Hadley and I wanted to get us straight again. So I decided to get us out of Paris and the temptation of Pauline. Hadley and I packed up that winter and went to Austria, to Schruns, with Bumby [their toddler son, Jack] to ski. We stayed at the Hotel Taube, a couple of dollars a day for all three of us. I was going to cut Pauline off. But, shitmaru, she followed us to Schruns, booked herself into the Taube, said she wanted to learn to ski, would I give her lessons. Hadley wasn’t happy about it, but she was a good sport. Actually, Pauline wasn’t nearly as good as Hadley skiing or horseback riding, shooting, fishing, name it.

“When Pauline had to go back to Paris, I was relieved that maybe alone with Hadley, I could shape up and lose the pressure of loving both of them.

“But a cable arrived from Max Perkins, editor at Scribner, with the terrific news they were going to publish Sun Also Rises. Would I go to New York for contracts and all that. I took off for Paris immediately and booked myself on the first decent boat, four days later. Hadley and Bumby stayed in Schruns and I said I’d return as soon as I got back from New York.

“Pauline showed up the minute I set foot in Paris. I spent those four nights in her bed until my boat left for New York.

“When I went back to Paris with my book contract in my pocket I should have gone directly to Schruns, where Hadley and Bumby had been waiting the 19 days I had been gone. But Pauline met my boat train when I arrived in Paris. I passed up three trains to stay with her at her place.

“When I did arrive at the Schruns station, Hadley was standing there, lovely Hadley, and little Bumby, husky and snow-tanned. At that moment I wished I had died before loving anyone else.

“Hadley and I had a happy time that winter in Schruns, skiing and poker games, singing and drinking with the locals at the bar.

“But, Christ, soon as we returned to Paris in the spring, I fell back with Pauline. It went like that all that spring.

“I worked hard and finished revising the book, working on the galleys. It was now ready for publication.

“Hadley did hold on for a while, but we had withdrawn from each other. I was asking too much of her. We decided to split up.

“I went to Gerald Murphy’s sixth-floor studio at 69, rue Froidevaux, which he [an American friend] had offered to me. Also, knowing I was broke, he slipped 400 bucks into my checking account at the Morgan Guaranty, which I used to repay some debts.”

**********

The next time we actually got together was in the summer of 1955. On the morning of July 4, I flew to Miami, caught a small afternoon plane to Key West and took a taxi to 414 Olivia Street. The main house was a stone Spanish Colonial with a veranda. Ernest had not lived there since 1940, when, after a long separation, he was divorced from Pauline; it had become her property as part of the divorce settlement and she had lived there until her recent death, when the property had passed to the children. But the children did not want to live there. So it fell to Ernest to come over from Cuba, where he lived in the Finca Vigía in San Francisco de Paula to arrange for a broker to rent it or maybe sell it.

Ernest, wearing swim trunks, came from the main house to greet me.

At dusk, we sat on the terrace as the first pale fireworks invaded the sky. “This is where I wrote ‘The Snows of Kilimanjaro,’ and that’s as good as I have any right to be, but now that I’m here, it’s not an escape, it just reminds me of a disturbing part of my life. I should have known better than to even hope for redemption.”

I asked him what had occurred after he and Hadley went their separate ways. Did he continue seeing Pauline? He said of course, she made sure of that, but he’d kept up his obligation to spend time with Bumby.

“On one of those times I came to get him, Hadley intercepted me and said it was time we talked.

“She picked up a pen and a sheet of paper. ‘So there’s no misunderstanding,’ she said. Then she wrote, ‘If Pauline Pfeiffer and Ernest Hemingway do not see each other for one hundred days, and if at the end of that time Ernest Hemingway tells me that he still loves Pauline Pfeiffer, I will, without further complication, divorce Ernest Hemingway.’ She signed her name and offered the pen to me. I said it read like a goddamn death warrant. ‘It is,’ she said. ‘Either she dies or I do.’ Never in my life signed anything with more reluctance. Took the pen and signed.

“‘Hadley,’ I said, ‘I love you, I truly do—but this is a peculiar passion I have for her that I can’t explain.’

“That night I had dinner with Pauline and told her about the hundred days. She smiled and said that was perfectly okay with her. She took a rose from the vase on the table and handed it to me and told me to be sure to press it under our mattress.

“Pauline exiled herself to her hometown of Piggott, Arkansas, population 2,000.

“Before leaving, she left me a message that we were destined to face life together, and that’s that. She said she had the wherewithal for us to live very well.

“I had settled into Murphy’s studio,” he said. “The outside view was of the Cimetière du Montparnasse. With the prospect of one hundred days of misery ahead of me, I was ready for one of the tombstones: Here lies Ernest Hemingway, who zigged when he should have zagged.”

**********

On the evening of the third day of my Key West visit, Ernest decided he and I should get food and drink at his favorite haunt, Sloppy Joe’s, Key West’s most celebrated saloon. I thought this was a good time to get Ernest back to talking about the hundred days.

“Was The Sun Also Rises published by then?”

“Just elbowing its way into the bookstores.

“It’s true that drinking ratcheted up my anguish. That and daily letters from Pauline, lamenting the pitfalls of boring Piggott, plus her wild yearning for me.”

“What about Fitzgerald during this period?” I asked.

“When I described my hundred-day predicament, he was very much on Hadley’s side.

“Scott asked me if they were really different, distinct from each other. I said yes, they were, that Hadley was simple, old-fashioned, receptive, plain, virtuous; Pauline up-to-the-second chic, stylish, aggressive, cunning, nontraditional.“Scott asked if they differed as sex partners. ‘Night and day,’ I told him. ‘Hadley submissive, willing, a follower. Pauline explosive, wildly demonstrative, in charge, mounts me. They’re opposites. Me in charge of Hadley and Pauline in charge of me.’

“‘Ernest, listen,’ he said, ‘the important thing is that you should be in charge of you. You need the shining qualities of Hadley. Her buoyancy. Neither Pauline or her money can provide that.’”

The following day was very hot, buzzing squadrons of insects hovering over the garden. We sat on the edge of the shady side of the pool, our legs in the water.

“Those black days,” he said, shaking his head. “I marked them off my calendar the way a convict marks his. The nights were particularly bad, but some places helped take my mind off them. One of them was Le Jockey, a classy nightclub in Montparnasse—wonderful jazz, great black musicians who were shut out in the States but welcomed in Paris. One of those nights, I couldn’t take my eyes off a beautiful woman on the dance floor—tall, coffee skin, ebony eyes, long, seductive legs: Very hot night, but she was wearing a black fur coat. The woman and I introduced ourselves.

“Her name was Josephine Baker, an American, to my surprise. Said she was about to open at the Folies Bergère, that she’d just come from rehearsal.

“I asked why the fur on a warm night in June. She slid open her coat for a moment to show she was naked. ‘I just threw something on,’ she said; ‘we don’t wear much at the Folies. Why don’t you come? I’m headlining as the ebony goddess.’ She asked if I was married. I said I was suspended, that there were two women, one my wife, and neither wanted to compromise.

“‘We should talk,’ she said. She’d once had a situation like that.

“I spent that night with Josephine, sitting at her kitchen table, drinking champagne sent by an admirer. I carried on nonstop about my trouble, analyzing, explaining, condemning, justifying, mostly bullshit. Josephine listened, intense, sympathetic; she was a hell of a listener. She said she, too, had suffered from double love.

“The rest of that night, into dawn, we talked about our souls, how I could convince my soul that despite my rejection of one of these women and inflicting hurt on her, it shouldn’t reject me.”

“So, Papa,” I asked, “what happened when the hundred days ended? ”

“It didn’t.”

“Didn’t what?”

“The end started on the seventy-first day that I marked off my calendar. I was having a drink at the Dingo Bar. I was using the Dingo as my mail drop, and on this night the bartender handed me my accumulated mail. My breath caught in my throat. Why would Hadley write to me? I dreaded opening it. ‘Dear Ernest,’ Hadley’s handwriting, only a few lines. It said although thirty days short of the time she had set, she had decided to grant me the divorce I obviously wanted. She was not going to wait any longer for my decision, which she felt was obvious.

“I needed to walk. There was a late-rising moon.

“I was relieved when the dawn finally broke. I went back up the old worn stone steps, heading for Murphy’s studio. I sat down at the desk, began to write a letter to Hadley. I told her I was informing Scribner that all of my royalties from The Sun Also Rises should go to her. I admitted that if I hadn’t married her I would never have written this book, helped as I was by her loyal and loving backing and her actual cash support. I told her that Bumby was certainly lucky to have her as his mother. That she was the best and honest and loveliest person I had ever known. I had achieved the moment I had tenaciously sought, but I wasn’t elated, nor did I send a cable to Pauline. What I felt was the sorrow of loss. I had contrived this moment, but I felt like the victim.

“I wrote to Pauline, telling her the swell news that Hadley had capitulated and that she could now come back to Paris.”

I asked him what happened when Pauline returned to Paris.

“We had never discussed marriage, and certainly I wasn’t of a mind to rush into it without a decent transition, if at all. But not Pauline. She immediately booked a church for the wedding, fashionable Saint-Honoré-d’Eylau in the Place Victor-Hugo.

“I made my regular visits to Hadley’s apartment to pick up Bumby. Hadley usually absented herself, but one time she was still there when I arrived. Rather to my surprise, not having planned it, there suddenly blurted out of me that if she wanted me, I would like to go back to her. She smiled and said things were probably better as they were. Afterward, I spent some time at the Dingo Bar berating myself.

“For the wedding, Pauline wore a dress designed for her by Lanvin, a strand of Cartier pearls, and a hairdo sculptured close to her head. For my part, I wore a tweed suit with a vest and a new necktie.”

**********

The following day in Key West, Ernest didn’t appear until late afternoon.

“You ever read that old bugger Nietzsche ?” he asked.

“A little,” I said.

“You know what he said about love? Said it’s a state where we see things widely different from what they are.”

“Pauline ?”

“Yup. It didn’t take long to unsee those things. I guess it started when we went to live with her folks in Piggott.”

“A lot of books were being written about the First World War we had fought against the Germans in France and Germany, but I had a monopoly on Italy and the part of the war I was in there. I wrote early every morning in Piggott before the suffocating heat took over. The days and nights were as bleak as a stretch of Sahara Desert.

“The gloom intensified when I received a letter from Fitzgerald telling me that Hadley had remarried with Paul Mowrer, a journalist I knew. Gentle, thoughtful man, he was Paris correspondent for the Chicago Daily News. What threw me was how quickly Hadley had married.

“My fantasy was that she would still be single when, as it seemed more and more likely, I would leave Pauline and return to her and Bumby.

“As depressing as existence was in Piggott, it got even worse when Pauline announced she was pregnant. Just as marriage had reared up too soon, so was I not ready for the upset of having a baby around. Pauline had a horrendous battle in the delivery room for 18 grueling hours that surrendered to a cesarean operation.

“I got in touch with an old friend, Bill Horne, met up with him in Kansas City, and drove to a dude ranch in Wyoming, where, praise the Lord, I had a really good three weeks away from Pauline, the squalation, and the Piggott clan. I worked mornings on my new book, A Farewell to Arms.

“I’ll tell you when I threw in the towel on Pauline.” Ernest said, “When she announced she was going to have another baby. The first one had made me bughouse and a second one, howling and spewing, would finish me off. And it nearly did.

“The baby was another boy—this one we named Gregory—even more of a howler and squawler than Patrick, so, as before, I got out of Piggott fast. I went for a two-week spell in Cuba. The two weeks stretched to two months.

“I spent most of my evenings with a 22-year-old beauty named Jane Mason, who came from uppity Tuxedo Park, New York, just about the least inhibited person I’d ever known.”

“Did Pauline know about her?” I asked.

“Made sure she did. ”

“You were giving her plenty of ammunition for a divorce? ”

“It was time. But Pauline was not going to give in no matter what.”

“As a lure to keep me in Key West, Pauline convinced her uncle Gus to pony up for the Pilar, the boat we fish on when you’re in Cuba. Why don’t we go out tomorrow? Gregory will put out a couple of lines. I don’t think the marlin are running right now, but there’s plenty else.”

Gregorio Fuentes was skilled in handling the boat when Ernest had a marlin strike. I had no doubt Gregorio was the inspiration for the old man in The Old Man and the Sea.

“I made a mistake with Pauline, that’s all. A goddamn fatal mistake. She tried to use her wealth to connect us, but it just put me off.”

“You must have been relieved,” I said, “finally getting your divorce from Pauline.”

“Pretty much, but it had its sad downside. After my shaky beginning with the boys—I told you about taking off when they were babies; I’m just no good at those first couple of diaper and colic years—but afterward I tried to make up for it.”

“You’re right,” I said, “that’s sad about the boys.”

“Something even sadder happened.” He slowly shook his head, remembering an interlude in Paris.

“I was at Lipp’s [Brasserie] on their enclosed terrace having a drink—there was a taxi stand there and a cab pulled up to discharge a passenger and damn if it wasn’t Hadley. Hadn’t laid eyes on her since our divorce. She was very well dressed and as beautiful as I remembered her. As I approached her, she saw me, gasped, and threw her arms around me. Having her up against me shortened my breath. She stepped back and looked at me.”

“‘My goodness, Ernest,’ she said. ‘You look the same.’”

“‘Not you.’”

“‘Oh?’”

“‘You look even lovelier.’”

“‘I follow you in the newspapers. A Farewell to Arms was wonderful. You’re a romantic, you know.’”

“‘You still married to what’s his name?’”

“‘Yes, I’m still Mrs. What’s His Name.’”

I invited her into Lipp for champagne. We discussed people we knew and what had become of them. I said, ‘You know, Hadley, I think about you often.’”

“‘Even now?’”

“‘You know what I’m remembering—that evening when The Sun Also Rises was published, and I put on my one necktie and we went to the Ritz and drank champagne with fraises des bois in the bottom of the glass. There’s something romantic about poverty when you’re young and hopeful.’”

“I asked if she could have dinner with me. She looked at me, remembering me. She gave it some thought.

“I said, ‘I have no sinister motive—just to look at you across a table for a little while.’”

“‘You know, Ernest,’ she said, ‘if things hadn’t been so good between us, I might not have left you so quickly.’”

“‘How many times I thought I saw you passing by. Once in a taxi stopped at a light. Another time in the Louvre I followed a woman that had the color of your hair and the way you walk and the set of your shoulders. You would think that with the passage of time, not being with you or hearing from you, you would fade away, but no, you are as much with me now as you were then.’”

“‘And I’ll always love you, Tatie. As I loved you in Oak Park and as I loved you here in Paris.’ She raised her glass and touched it with mine. She drank the last of her champagne and put down her glass. ‘I must go to my appointment,’ she said.

“I accompanied her to the corner and waited with her for the light to change. I said I remembered those dreams we dreamed with nothing on our table and the wine bottle empty. ‘But you believed in me against those tough odds. I want you to know, Hadley, you’ll be the true part of any woman I write about. I’ll spend the rest of my life looking for you.’

“‘Good-bye, my Tatie.’

“The light changed to green. Hadley turned and kissed me, a meaningful kiss; then she crossed the street and I watched her go, that familiar, graceful walk.”

Ernest leaned his head back and closed his eyes, perhaps seeing Hadley, turning her head to take a last look at him before disappearing into the crowded sidewalk.

“That was the last time I saw her.”

Excerpt from Hemingway in Love by A.E. Hotchner. Copyright © 2015 by the author and reprinted with the permission of the publisher, St. Martin’s Press.