Fabric of Their Lives

There’s a new exhibition of works by the quilters of Gee’s Bend, Alabama, whose lives have been transformed by worldwide acclaim for their artistry

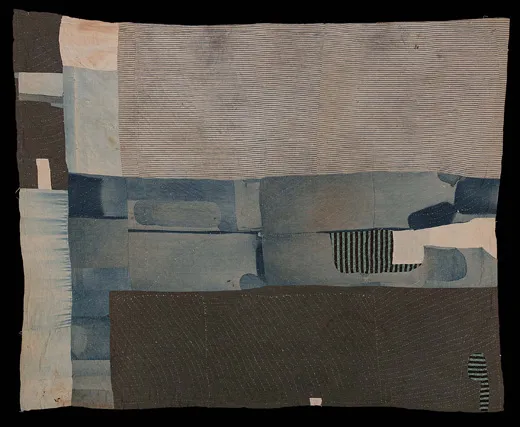

Annie Mae Young is looking at a photograph of a quilt she pieced together out of strips torn from well-worn cotton shirts and polyester pants. "I was doing this quilt at the time of the civil rights movement," she says, contemplating its jazzy, free-form squares.

Martin Luther King Jr. came to Young's hometown of Gee's Bend, Alabama, around that time. "I came over here to Gee's Bend to tell you, You are somebody," he shouted over a heavy rain late one winter night in 1965. A few days later, Young and many of her friends took off their aprons, laid down their hoes and rode over to the county seat of Camden, where they gathered outside the old jailhouse.

"We were waiting for Martin Luther King, and when he drove up, we were all slappin' and singin'," Young, 78, tells me when I visit Gee's Bend, a small rural community on a peninsula at a deep bend in the Alabama River. Wearing a red turban and an apron bright with pink peaches and yellow grapes, she stands in the doorway of her brick bungalow at the end of a dirt road. Swaying to a rhythm that nearly everyone in town knows from a lifetime of churchgoing, she breaks into song: "We shall overcome, we shall overcome...."

"We were all just happy to see him coming," she says. "Then he stood out there on the ground, and he was talking about how we should wait on a bus to come and we were all going to march. We got loaded on the bus, but we didn't get a chance to do it, 'cause we got put in jail," she says.

Many who marched or registered to vote in rural Alabama in the 1960s lost their jobs. Some even lost their homes. And the residents of Gee's Bend, 60 miles southwest of Montgomery, lost the ferry that connected them to Camden and a direct route to the outside world. "We didn't close the ferry because they were black," Sheriff Lummie Jenkins reportedly said at the time. "We closed it because they forgot they were black."

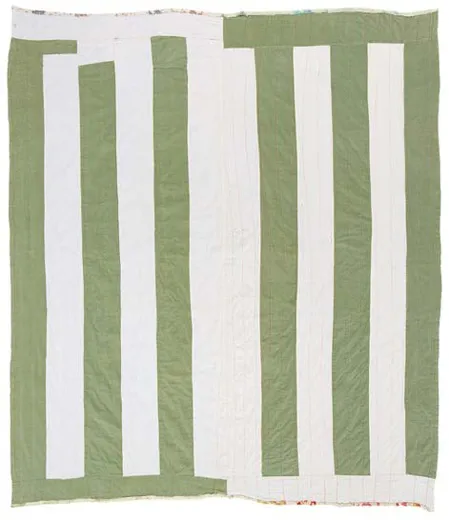

Six of Young's quilts, together with 64 by other Gee's Bend residents, have been traveling around the United States in an exhibition that has transformed the way many people think about art. Gee's Bend's "eye-poppingly gorgeous" quilts, wrote New York Times art critic Michael Kimmelman, "turn out to be some of the most miraculous works of modern art America has produced. Imagine Matisse and Klee (if you think I'm wildly exaggerating, see the show), arising not from rarefied Europe, but from the caramel soil of the rural South." Curator Jane Livingston, who helped organize the exhibition with collector William Arnett and art historians John Beardsley and Alvia Wardlaw, said that the quilts "rank with the finest abstract art of any tradition." After stops in such cities as New York, Washington, D.C., Cleveland, Boston and Atlanta, "The Quilts of Gee's Bend" will end its tour at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco's de Young Museum December 31.

The bold drama of the quilt Young was working on in 1965 is also found in a quilt she made out of work clothes 11 years later. The central design of red and orange corduroy in that quilt suggests prison bars, and the faded denim that surrounds it could be a comment on the American dream. But Young had more practical considerations. "When I put the quilt together," she says, "it wasn’t big enough, and I had to get some more material and make it bigger, so I had these old jeans to make it bigger."

Collector William Arnett was working on a history of African-American vernacular art in 1998 when he came across a photograph of Young’s work-clothes quilt draped over a woodpile. He was so knocked out by its originality, he set out to find it. A couple of phone calls and some creative research later, he and his son Matt tracked Young down to Gee's Bend, then showed up unannounced at her door late one evening. Young had burned some quilts the week before (smoke from burning cotton drives off mosquitoes), and at first she thought the quilt in the photograph had been among them. But the next day, after scouring closets and searching under beds, she found it and offered it to Arnett for free. Arnett, however, insisted on writing her a check for a few thousand dollars for that quilt and several others. (Young took the check straight to the bank.) Soon the word spread through Gee's Bend that there was a crazy white man in town paying good money for raggedy old quilts.

When Arnett showed photos of the quilts made by Young and other Gee's Benders to Peter Marzio, of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (MFAH), he was so impressed that he agreed to put on an exhibition. "The Quilts of Gee’s Bend" opened there in September 2002.

The exhibition revived what had been a dying art in Gee's Bend. Some of the quilters, who had given in to age and arthritis, are now back quilting again. And many of their children and grandchildren, some of whom had moved away from Gee's Bend, have taken up quilting themselves. With the help of Arnett and the Tinwood Alliance (a nonprofit organization that he and his four sons formed in 2002), fifty local women founded the Gee's Bend Quilters Collective in 2003 to market their quilts, some of which now sell for more than $20,000. (Part goes directly to the maker, the rest goes to the collective for expenses and distribution to the other members.)

Now a second exhibition, "Gee’s Bend: The Architecture of the Quilt," has been organized by the MFAH and the Tinwood Alliance. The show, which opened in June, features newly discovered quilts from the 1930s to the 1980s, along with more recent works by established quilters and the younger generation they inspired. The exhibition will travel to seven other venues, including the Indianapolis Museum of Art (October 8-December 31) and the Orlando Museum of Art (January 27-May 13, 2007).

Arlonzia Pettway lives in a neat, recently renovated house off a road plagued with potholes. The road passes by cows and goats grazing outside robin's-egg blue and brown bungalows. "I remember some things, honey," Pettway, 83, told me. (Since my interview with her, Pettway suffered a stroke, from which she is still recovering.) "I came through a hard life. Maybe we weren't bought and sold, but we were still slaves until 20, 30 years ago. The white man would go to everybody's field and say, 'Why you not at work?'" She paused. "What do you think a slave is?"

As a girl, Pettway would watch her grandmother, Sally, and her mother, Missouri, piecing quilts. And she would listen to their stories, many of them about Dinah Miller, who had been brought to the United States in a slave ship in 1859. "My great-grandmother Dinah was sold for a dime," Pettway said. "Her dad, brother and mother were sold to different people, and she didn't see them no more. My great-grandfather was a Cherokee Indian. Dinah was made to sleep with this big Indian like you stud your cow.... You couldn't have no skinny children working on your slave master's farm." In addition to Pettway, some 20 other Gee's Bend quiltmakers are Dinah's descendants.

The quilting tradition in Gee's Bend may go back as far as the early 1800s, when the community was the site of a cotton plantation owned by a Joseph Gee. Influenced, perhaps, by the patterned textiles of Africa, the women slaves began piecing strips of cloth together to make bedcovers. Throughout the post-bellum years of tenant farming and well into the 20th century, Gee’s Bend women made quilts to keep themselves and their children warm in unheated shacks that lacked running water, telephones and electricity. Along the way they developed a distinctive style, noted for its lively improvisations and geometric simplicity.

Gee's Bend men and women grew and picked cotton, peanuts, okra, corn, peas and potatoes. When there was no money to buy seed or fertilizer, they borrowed one or both from Camden businessman E. O. Rentz, at interest rates only those without any choice would pay. Then came the Depression. In 1931 the price of cotton plummeted, from about 40 cents a pound in the early 1920s, to about a nickel. When Rentz died in 1932, his widow foreclosed on some 60 Gee's Bend families. It was late fall, and winter was coming.

"They took everything and left people to die," Pettway said. Her mother was making a quilt out of old clothes when she heard the cries outside. She sewed four wide shirttails into a sack, which the men in the family filled with corn and sweet potatoes and hid in a ditch. When the agent for Rentz's widow came around to seize the family's hens, Pettway's mother threatened him with a hoe. "I'm a good Christian, but I'll chop his damn brains out," she said. The man got in his wagon and left. "He didn't get to my mama that day," Pettway told me.

Pettway remembered that her friends and neighbors foraged for berries, hunted possum and squirrels, and mostly went hungry that winter until a boat with flour and meal sent by the Red Cross arrived in early 1933. The following year, the Federal Emergency Relief Administration provided small loans for seed, fertilizer, tools and livestock. Then, in 1937, the government's Resettlement Administration (later the Farm Security Administration) bought up 10,000 Gee's Bend acres and sold them as tiny farms to local families.

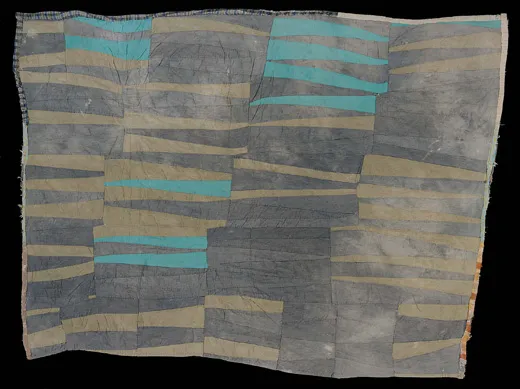

In 1941, when Pettway was in her late teens, her father died. "Mama said, 'I'm going to take his work clothes, shape them into a quilt to remember him, and cover up under it for love.'" There were hardly enough pants legs and shirttails to make up a quilt, but she managed. (That quilt—jostling rectangles of faded gray, white, blue and red—is included in the first exhibition.) A year later, Arlonzia married Bizzell Pettway and moved into one of the new houses built by the government. They had 12 children, but no electricity until 1964 and no running water until 1974. A widow for more than 30 years, Arlonzia still lives in that same house. Her mother, Missouri, who lived until 1981, made a quilt she called "Path Through the Woods" after the 1960s freedom marches. A quilt that Pettway pieced together during that period, "Chinese Coins", is a medley of pinks and purples—a friend had given her purple scraps from a clothing factory in a nearby town.

"At the time I was making that quilt, I was feeling something was going to happen better, and it did," Pettway says. "Last time I counted I had 32 grandchildren and I think between 13 and 14 great-grands. I'm blessed now more than many. I have my home and land. I have a deepfreeze five feet long with chicken wings, neck bones and pork chops."

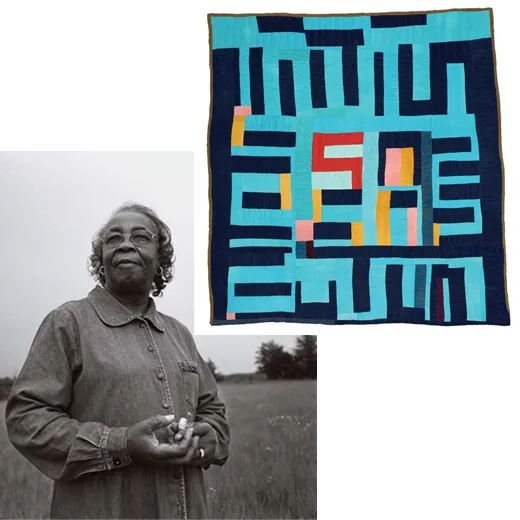

The first exhibition featured seven quilts by Loretta Pettway, Arlonzia Pettway's first cousin. (One in three of Gee's Bend’s 700 residents is named Pettway, after slave owner Mark H. Pettway.) Loretta, 64, says she made her early quilts out of work clothes. "I was about 16 when I learned to quilt from my grandmama," she says. "I just loved it. That's all I wanted to do, quilt. But I had to work farming cotton, corn, peas and potatoes, making syrup, putting up soup in jars. I was working other people's fields too. Saturdays I would hire out; sometimes I would hire out Sundays, too, to give my kids some food. When I finished my chores, I'd sit down and do like I'm doing now, get the clothes together and tear them and piece. And then in summer I would quilt outside under the big oak." She fingers the fabric pieces in her lap. "I thank God that people want me to make quilts," she says. "I feel proud. The Lord lead me and guide me and give me strength to make this quilt with love and peace and happiness so somebody would enjoy it. That makes me feel happy. I'm doing something with my life."

In 1962 the U.S. Congress ordered the construction of a dam and lock on the Alabama River at Miller's Ferry, just south of Gee's Bend. The 17,200-acre reservoir created by the dam in the late 1960s flooded much of Gee's Bend's best farming land, forcing many residents to give up farming. "And thank God for that," says Loretta. "Farming wasn't nothing but hard work. And at the end of the year you couldn't get nothing, and the little you got went for cottonseed."

Around that time, a number of Gee's Bend women began making quilts for the Freedom Quilting Bee, founded in 1966 by civil rights worker and Episcopalian priest Francis X. Walter to provide a source of income for the local community. For a while, the bee (which operated for about three decades) sold quilts to such stores as Bloomingdale's, Sears, Saks and Bonwit Teller. But the stores wanted assembly-line quilts, with orderly, familiar patterns and precise stitching—not the individual, often improvised and unexpected patterns and color combinations that characterized the Gee's Bend quilts.

"My quilts looked beautiful to me, because I made what I could make from my head," Loretta told me. "When I start I don't want to stop until I finish, because if I stop, the ideas are going to go one way and my mind another way, so I just try to do it while I have ideas in my mind."

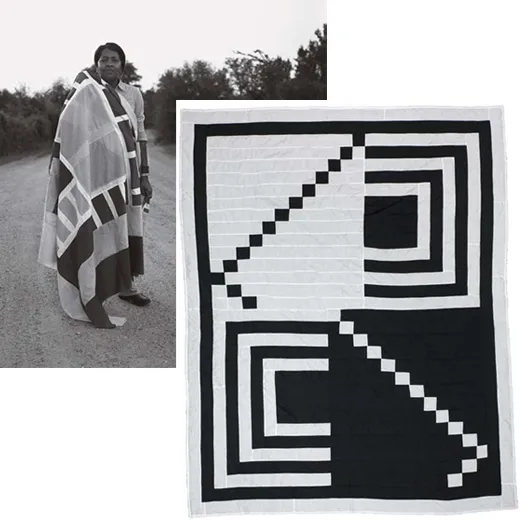

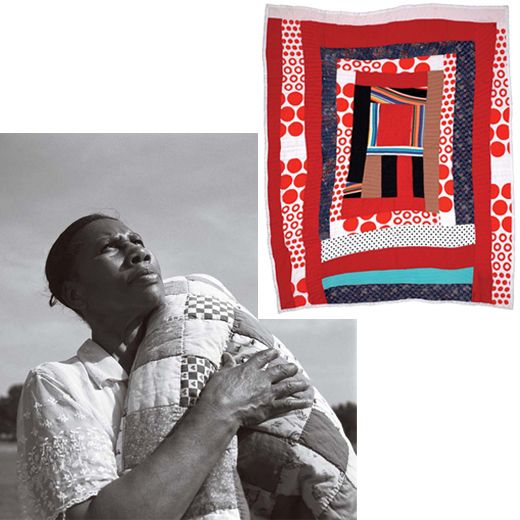

Loretta had been too ill to attend the opening of the first exhibition in Houston. But she wore a bright red jacket and a wrist corsage of roses to the opening of the second show last spring. Going there on the bus, "I didn't close my eyes the whole way," she says. "I was so happy, I had to sightsee." In the new show, her 2003 take on the popular "Housetop" pattern—a variant of the traditional "Log Cabin" design—is an explosion of red polka dots, zany stripes and crooked frames within frames (a dramatic change from the faded colors and somber patterns of her early work-clothes quilts). Two other quilts made by Loretta are among those represented on a series of Gee's Bend stamps issued this past August by the U.S. Postal Service. "I just had scraps of what I could find," she says about her early work. "Now I see my quilts hanging in a museum. Thank God I see my quilts on the wall. I found my way."

Mary Lee Bendolph, 71, speaks in a husky voice and has a hearty, throaty laugh. At the opening of the new exhibition in Houston, she sported large rhinestone earrings and a chic black dress. For some years, kidney disease had slowed her quiltmaking, but the first exhibition, she says, "spunked me to go a little further, to try and make my quilts a little more updated." Her latest quilts fracture her backyard views and other local scenes the way Cubism fragmented the cafés and countryside of France. Her quilts share a gallery with those of her daughter-in-law, Louisiana Pettway Bendolph.

Louisiana now lives in Mobile, Alabama, but she remembers hot, endless days picking cotton as a child in the fields around Gee’s Bend. From age 6 to 16, she says, the only time she could go to school was when it rained, and the only play was softball and quiltmaking. Her mother, Rita Mae Pettway, invited her to the opening in Houston of the first quilt show. On the bus ride home, she says, she "had a kind of vision of quilts." She made drawings of what would become the quilts in the new exhibition, in which shapes seem to float and recede as if in three dimensions.

"Quilting helped redirect my life and put it back together," Louisiana says. "I worked at a fast-food place and a sewing factory, and when the sewing factory closed, I stayed home, being a housewife. You just want your kids to see you in a different light, as someone they can admire. Well, my children came into this museum, and I saw their faces."

To Louisiana, 46, quiltmaking is history and family. "We think of inheriting as land or something, not things that people teach you," she says. "We came from cotton fields, we came through hard times, and we look back and see what all these people before us have done. They brought us here, and to say thank you is not enough." Now her 11-year-old granddaughter has taken up quiltmaking; she, however, does her drawings on a computer.

In Gee's Bend not long ago, her great-grandmother Mary Lee Bendolph picked some pecans to make into candy to have on hand for the children when the only store in town is closed, which it often is. Then she soaked her feet. Sitting on her screened-in porch, she smiled. "I'm famous," she said. "And look how old I am." She laughed. "I enjoy it."