Filipino Cuisine Was Asian Fusion Before “Asian Fusion” Existed

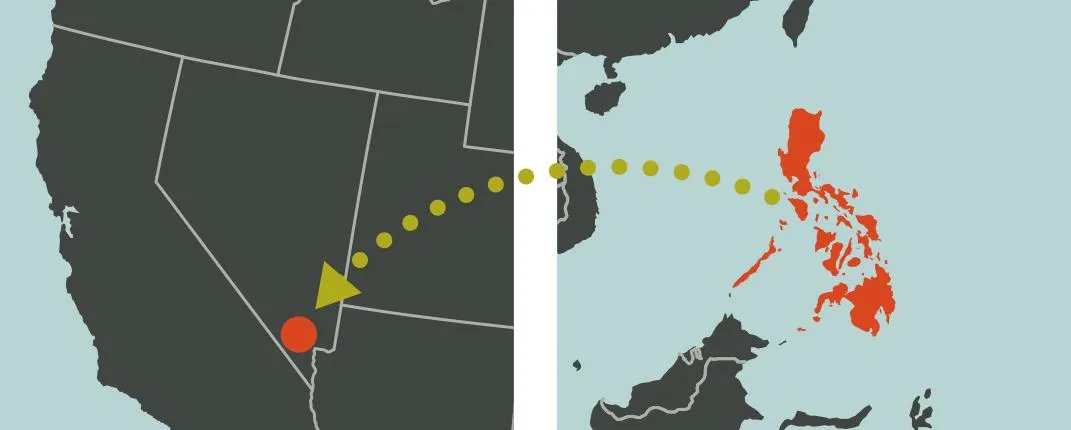

A wave of Filipino families in Las Vegas is putting a Pacific spin on fried chicken, hot dogs and Sin City itself

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ee/49/ee497e74-4ff8-4fd2-8cb2-c540b10354ff/apr2015_c02_foodfilipino.jpg)

If you are a typical American, especially one who was born and raised here as we were, you probably believe—know—as we did that, Americans have a lock on fried chicken. Then we met Salve Vargas Edelman, who took us to her favorite Manila chicken joint. But this place, Max’s Restaurant, wasn’t in Manila. It was in Las Vegas, in a strip mall, a few miles past Caesars Palace, and it was there that we were fortuitously, deliciously, humbled.

Vargas Edelman, who was born in the Philippines, is a singer and bandleader who has toured the world. She is also a real estate agent, president of the Lions Club, host of a local television program called “Isla Vegas, the Ninth Island,” and president of the Rising Asian Pacific Americans Coalition for Diversity, which she founded. It’s at the RAPACD’s cultural center, a one-story bungalow on the grounds of a neighborhood park, that we first met her.

“This is my baby,” she said with a sweep of her arms, “17 years in the making.” Years before, not long after moving to Las Vegas from San Francisco, where she lived after leaving the Philippines in 1980, Vargas Edelman noticed a sign for an Asian American center. “I followed it, looking for the building, but all there was was a sign,” she recalled. Filipinos are a rapidly emerging demographic force in Las Vegas—between 2000 and 2010, the Filipino population in Nevada reportedly grew by 142 percent, so that there are now more Filipinos than members of any other Asian nation in the state. When they ask for a community center, they get more than a sign: They get a building, too.

They also get Max’s Restaurant of the Philippines, an institution back home with 160 outlets, which recently opened its first branch in Las Vegas. And with Max’s comes its signature dish, Pinoy fried chicken: unbreaded, marinated in fish sauce and ginger, then fried till the skin turns cordovan and crisp and the butter-soft meat underneath slips off the bone.

It’s at Max’s that we next meet Vargas Edelman and a few of her friends, leaders in the Filipino community, each, like her, a model of civic engagement, the kind that Tocqueville celebrated in his 19th-century classic Democracy in America, the same kind that 20th-century sociologists said was done for. But those sociologists, clearly, hadn’t been to Vegas. “The nice thing is, we brought our culture here,” Vargas Edelman said. “The bayanihan system. It means unity, solidarity.” A case in point: When Typhoon Haiyan cut across the central Philippines in November 2013, members of the Vegas Filipino community mobilized instantly, holding fund-raisers that continue to funnel money and goods back home. And speaking of home, they are also building 20 new homes in the area most devastated. They call the project “Vegas Village.”

We are dining on a whole Pinoy fried chicken and pancit—thin rice noodles tossed with shrimp that often comes with chicken and pork mixed in as well—and garlic rice (tastes like it sounds), and chicken adobo, a stew of onions, garlic and meat that is at once salty, tangy and sweet. Adobo is the Spanish word for marinade, but it’s what is in the marinade that distinguishes Filipino adobo from any other: one of its main ingredients is vinegar, which gives the stew its distinctive, pleasant buzz. Adobo predates the colonization of the Philippines in the 16th century, when cooking with vinegar was an effective way to preserve meat. The conquerors gave adobo its name, but the colonists gave it its flavor.

Edna White puts some adobo on her plate with fried chicken and pancit, declares it “comfort food” and mentions that she’s been up all night packing 20 large containers of clothes and supplies for typhoon victims. It’s just “a little something” she’s been doing on the side for months while running a print shop and working part time at a local hospital as a nurse, ever since the storm devastated the town where she grew up and where her sister still lives.

“After the typhoon, I tried to find her for four days. I’d call every night and no one would pick up,” White recalled. “Eventually my sister was able to get to an area about two hours away from where she lived that had not been hit so hard and I was finally able to get through to her. I was so relieved. She said she had not eaten in three days. I asked her why she didn’t eat coconuts, and she told me that all the trees had been ripped out of the ground and everything was underwater and there were no coconuts. I told her not to go anywhere, to stay in that town and wait and I would send her $200. I told her that when she got it, to take the money and buy as much rice as she could and then go back and share it with everyone. Because of course you can’t be eating when no one else is.

“At first I was just trying to help the people I knew, sending money and candles and matches—they didn’t have electricity—but there were so many people who needed help and I was running out of money, so I went to a Republican Party meeting and the chairman let me talk and ask for help. People gave me $10, $20, even $100. I sent it over there and told people to take pictures of what they bought with it: chicken, rice noodles, hot dogs.”

Hot dogs figure in Filipino cuisine, though in a roundabout way. It starts with spaghetti, which was adapted after being introduced to the Philippine archipelago by the European traders who sailed along the South China Sea. Yet while it may look like standard-issue, Italian-style spaghetti topped with marinara, prepare to be surprised. Filipino spaghetti is sweet—in place of tomato sauce Pinoy cooks use banana ketchup, developed during World War II when tomatoes were in short supply—and it is chock-full of not meatballs, but sliced hot dogs.

Which is to say that Filipino cuisine was Asian fusion before there was Asian fusion. It has borrowed and modified elements of Chinese, Spanish, Malaysian, Thai and Mongolian cooking, to name just a few of its influences.

“We use rice noodles instead of the wheat noodles that the Chinese use,” explained Jason Ymson, the afternoon we met him and about 25 other Filipino community leaders for lunch at the Salo-Salo Grill & Restaurant. Ymson is the assistant chef at Twin Creeks steakhouse in the Silverton Casino, where he has been slowly working Filipino tastes into his pan-Asian creations. “Siopao—our steamed buns with meat inside—are a direct transliteration from the Chinese. Flan is Spanish but we have leche flan. Adobo is a common derivative of Chinese soy sauce chicken. Filipino cuisine is a hybrid, so there is a lot of leeway to play with it.”

Even so, “Filipino food is hard,” observed Rudy Janeo, a private caterer and chef at an Italian restaurant. “People don’t order it because they don’t know it, and they don’t know it because they don’t order it. Serve a fish with the head on and no one wants to eat it.”

“Because Americans haven’t been exposed to Filipino cuisine, the idea is to work in the Filipino elements bit by bit until you have a full-blown dish,” Ymson added. “The most challenging part is nailing the description correctly so you don’t scare people off.” He passes a dish of barbecued squid down the table, which we are instructed to eat two-fisted, skewered on a fork and carved with a spoon, a trick we have yet to master.

Jason Ymson is a pioneer, not only for his mission to introduce Filipino tastes into the mainstream American palate, but also because as a second-generation Filipino, born and raised in Las Vegas, he has made the transition into the mainstream himself.

“Back in the ’80s—I was born in 1984—Filipinos were a small niche community. When you went to a party you always saw the same people. As my generation began to assimilate, we moved out into other communities. The biggest evidence of assimilation is the accent. My mom is very traditional. She has been here since the 1970s and still has a thick accent. My father, who assimilated into American culture, has no accent. When I was first going to school, he would do my English homework too.”

Unlike Ymson, the typical Vegas Filipino has moved to the city from somewhere else in the United States. The community’s phenomenal growth is an aggregation, a resettlement from one part of America to another.

Rozita Lee, who in 2010 was appointed by President Barack Obama to his Advisory Commission on Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, has had a front row seat to this in-migration. She moved in 1979 from Hawaii to Las Vegas to join her husband, who had a medical practice here at the time. As we sipped bright orange cantaloupe juice at Salo-Salo, she took a pen from her handbag and drew on the paper tablecloth.

“First the casino and hotel workers came, followed by the entertainers and the professionals. Then Filipinos from other parts of the country, especially the Northeast, started to retire here. In the ’70s and ’80s, you got the middle class. In the 2000s, you got the rich. And then, after the economic downturn, around 2008, you started to see those who were not doing well, especially in California, come here for jobs.” When Lee stopped drawing, she had made several parallel lines. The point, she said, is that these different groups of Filipinos didn’t necessarily intersect.

If that was the rule, the exception was Seafood City, a colossal supermarket not far from the Las Vegas Strip, which was bustling on a Sunday morning as shoppers young, old and mostly Filipino snacked on siopao and lumpia (fried spring rolls filled with ground pork, onions and carrots) as they pushed carts along aisles filled with foods whose names were as exotic to us as the items themselves. There was bibingka, a deep purple, sweet rice-based dessert; and ginataan, a dessert made from coconut milk, potatoes, bananas and tapioca. There were duck eggs whose shells were crayon red, kaong (palm fruit in syrup), taro leaves in coconut cream, cheesy corn crunch and racks of shrimp paste, dried herring in oil, dried salted rabbitfish, quail eggs in brine and bottles of banana sauce. And that was before we got to the frozen food case, filled with birch flower, frozen banana leaves, squash flower, horseradish fruit, grated cassava, macapuno ice cream and cheese ice cream. And then there was the fish—moonfish, mudfish, pony fish, Bombay duck fish, belt fish, blue runner, redtail fusilier, Japanese amberjack, cabria bass, yellow stripe, tupig, milkfish. We could go on but won’t, since milkfish is the national fish of the Philippines.

Milkfish is also the centerpiece of bangus, a dish that has spawned its own festival, in Dagupan City, where people compete in deboning contests and costumed street dancers re-enact the milkfish harvest. The way it is served at Salo-Salo—wrapped in banana leaves and steamed with onions, ginger and tomatoes—is the way it’s prepared in Manila and by islanders in Negros Occidental. In other regions it may be grilled or broiled. Pinaputock na bangus—what we are having—is meaty and mildly piquant; the banana leaves have permeated the fish.

Now we are sampling laing—taro leaves cooked in coconut milk with grilled shrimp and chilies that are as green a vegetable as we’re likely to see. Amie Belmonte, who runs Fil-Am Power, an organization she started with her husband, Lee, and other community leaders to translate the Filipinos population surge into nonpartisan political clout, recalled how when she first moved to Las Vegas to run the city’s department of senior services, she used foods she’d grown up with to introduce herself. “The people I worked with thought I was Hawaiian. I had to explain that though I grew up in Hawaii, I was Filipino, from the Philippines. So I brought in lumpia and pancit and shared it. Food is the avenue into a culture.”

That has turned out to be true for second- and third-generation Filipino-Americans, too. As Jing Lim, who grew up in a Filipino community in Juneau, Alaska, told us, “Pretty much everything my three boys know about Filipino culture comes from food and family. And by family I don’t just mean the immediate family. I mean first cousins, second cousins, fifth cousins.”

“Our mainstay, as a culture, is our food,” said Roger Lim, Jing’s husband. “That’s what brings families together. We always eat family-style.”

A cuisine is created not only by ingredients and methods and tastes, but also from how that food is consumed and shared. For Filipinos, that cuisine starts and ends with family.

Family—connection—is what brought many Filipinos to the United States in the first place, often through a process called “petitioning,” where one family member could petition the American government to allow another family member to follow. After Edna White married an American and moved to the States—first to Oregon, then to Nevada—she petitioned for her mother to join her. For Salve Vargas Edelman it was her mother who petitioned her, having been petitioned herself by another daughter who had married an American serviceman. “Because I was single, the family decided I should be the one to take care of our mother, who was not well,” Vargas Edelman said. “Part of our culture is that we take care of our elders. My generation didn’t even know what rest homes were. It’s part of our religion, too. We believe in the Ten Commandments: Honor your mother and father.”

And it is not just parents. “We have this very nice Filipino tradition of respecting our elders,” Vargas Edelman’s friend, Cynthia Deriquito, added. “All your siblings, if they respect you, they follow you. From your profession down to how you live your life. And then our children are kind of copying it. Whatever the eldest does is mimicked.”

Deriquito, a board member of Fil-Am Power, is a former nurse—a profession practiced by many Filipino Americans, including her brother, two sisters, daughter and niece. “Since I was the first born and my dad died at 47, I sent my three siblings to nursing school. It’s not unusual. It’s not heroic. It’s just what you do.”

Another thing you do, especially at Max’s once you have finished your fried chicken, is have halo-halo for dessert. Imagine an ice-cream sundae, but instead of chocolate or vanilla, the ice cream is purple and made from yams, and instead of whipped cream, there is evaporated milk, and instead of nuts, there are boiled beans—garbanzo, white and red beans. Now add some coconut, palm fruit, pounded rice flakes, jackfruit and shaved ice. In Tagalog, the main language of the Philippines, halo-halo means “mix-mix” or “hodgepodge.” This hodgepodge is sweet and rich, different yet just at the edge of familiar. It reminded us of what Rhigel Tan told us that afternoon at Salo-Salo. Tan, a professor of nursing at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, is also a founder of Kalahi, an 80-person folkloric ensemble that performs traditional Filipino dances, songs and stories. “I believe in the beauty of diversity,” he said, “but I don’t believe in the melting pot. I believe in the stew pot. In the melting pot you lose your identity. In the stew pot, you’re the potato, I’m the carrots, and everyone knows who they are.”

Related Reads

The Adobo Road Cookbook

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/halpern_mckibben-edited.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/halpern_mckibben-edited.jpg)