Folk Art Jubilee

Self-taught artists and their fans mingle each fall at Alabama’s up close and personal Kentuck Festival

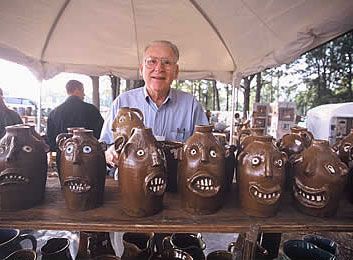

Under the towering pines hard by Alabama’s Black Warrior River, the talk at 8 a.m. on an October Saturday is of a forecast of rain. When the exhibited work of 38 folk artists is made of mud, cardboard, sticks and rags—and the exhibit is out-of-doors—wet weather can indeed mean a washout.

But for now the sun shines, merciful news for the 30,000 people expected today and tomorrow at the Kentuck Festival of the Arts, held the third weekend of every October in the woods near downtown Northport, across the river from Tuscaloosa. Here is America’s folk art at its most personal, a unique event where nationally acclaimed self-taught and primitive artists create, show and sell their work themselves. To see these “roots artists” otherwise would, in many cases, involve road trips through the backwoods and hollows of Alabama, Georgia and the Carolinas. Over its 32-year history, the show has taken on the homey atmosphere of a family reunion, with many buyers returning year after year to chat with the artists and add to their collections. (I am one of those fans; over the years, I’ve collected work by some of the artists featured on these pages.)

At the entrance to the festival, Sam McMillan, a 77-year-old artist from Winston-Salem, North Carolina, holds court, resplendent in a polka-dot daubed suit that matches the painted furniture, lamps and birdhouses for sale behind him. “People walk in and catch a sight of me and think, ‘Whoa now, what’s happening at this place today?’” says McMillan. “They know they’re in for something different.’’ Kentuck is the most intimate event of its kind in the nation, says Ginger Young, a visitor and art dealer in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. “For many of us, art encounters consist of hushed museum exhibitions and pretentious gallery openings,” she says. “Kentuck is unrivaled in its ability to blaze a direct connection between artists and art fans. What happens at Kentuck is akin to a good old-fashioned Southern revival.”

Kentuck (it’s named for an early settlement on the site of the present-day town; the origin of the word is unclear) began in 1971 as an offshoot of Northport’s centennial celebration. That first festival, says founding director Georgine Clarke, featured only 20 artists; two years later there were 35. “We quickly outgrew the downtown location and had our eyes on an overgrown park a little ways out of town,” she says. “Postmaster Ellis Teer and I walked around it to figure out how much of it we could mow—Ellis brought his lawn mower along—and that became the area we’d set up in. Each year we mowed a little bit more, and the festival grew that much.” The exhibition now covers half of the 38.5-acre park and showcases more than 200 traditional craftspeople quilting, forging metal, weaving baskets, making furniture and throwing pottery. But the big draw remains the extraordinary collection of authentic folk artists, each with stories to tell about how they started and where they get their inspiration. Many of the artists now have works in the permanent collections of museums like the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Baltimore’s AmericanVisionaryArt Museum and the New Orleans Museum of Art. But here at Kentuck, the artists can be found leaning against a rusty Olds Delta 88, playing a harmonica or picking a guitar, ready to chat.

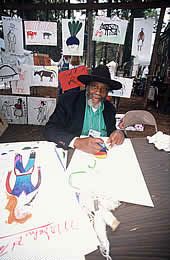

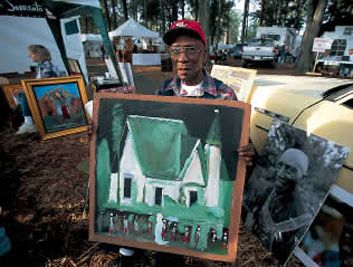

Jimmie Lee Sudduth, 93, is parked in a folding chair next to his car and is engulfed by a crowd that eagerly flips through his mud paintings, which are stacked against a tree. Sudduth, from nearby Fayette, Alabama, has been finger painting with mud since 1917. His work is in the collection of New York City’s American Folk Art Museum.

The typically taciturn Sudduth brightens as he recalls his breakthrough moment at age 7. “I went with Daddy and Mama to their jobs at a syrup mill and, with nothing better to do, smeared mud and honey on an old tree stump to make a picture,” he says. When he returned days later after several rains, the painting was still there; his mother, Vizola, saw it as a sign that he’d make a great painter, and encouraged her son. “That’s when I found out I had something that would stick,” says Sudduth. “I counted 36 kinds of mud near my house and used most of them one time or another.”

Eventually, Sudduth experimented with color. “I’d grab a handful of grass or berries and wipe them on the painting, and the juice comes out and makes my color,” he says. In the late 1980s, a collector who was concerned that Sudduth’s mudon-plywood paintings might fall apart gave the artist some house paint and encouraged him to incorporate it into his work. (Art dealer Marcia Weber, who exhibits Sudduth’s work in her Montgomery, Alabama, gallery, isn’t worried about how long his earliest mud works will last. “How permanent are the caves of Lascaux and Altamira?” she asks.) Sudduth now uses both paints and mud to render the houses of Fayette, trains, and his dog, Toto.

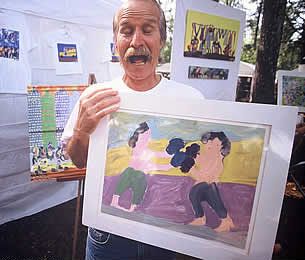

For the past 13 years, Woodie Long, 61, and his wife, Dot, 46, have made the drive up from Andalusia, Alabama, or, since 1996, the Florida panhandle, to show his work: rhythmic and undulating figures that dance across paper, wood, metal and glass in bright acrylics. Long, who had been a house painter for 25 years, started making art 15 years ago. His paintings, based on childhood memories, have names such as Jumping on Grandma’s Bed and Around the Mulberry Bush. “People look at my art and see themselves—it’s their memories too,” he says. “They just feel a part of it. Every day there are new people that see my work, and the response just blows me away.”

Sandra Sprayberry, 46, has introduced new people to Long’s work for about ten years. Sprayberry, an English professor at Birmingham-SouthernCollege, befriended Long when she took a group of students to meet him during a tour to visit Alabama folk artists. “I wanted the students to experience the stories these artists tell both orally and in their artwork,” she says. Sprayberry says that primitive folk art grabs her emotionally more than technically proficient art, and it was Long’s fluid lines that first caught her eye. “When other folk artists attempt to portray movement, it appears almost intentionally comical—which I often love,” she says. “But he paints it in a lyrical way in especially bright and vibrant colors. I love his perpetually childlike enthusiasm. And Woodie truly likes his paintings. Every time I pick one up, he says ‘I really love that one!’ He’s the real deal.”

Folk art is often referred to as visionary, self-taught or outsider art; experts don’t agree on a single descriptive term or even on what is, or isn’t, included in the category. They do agree, however, that unlike craftspeople who often train many years to attain extraordinary skill with materials, folk artists are largely untutored. Theirs is an often passionate, free-flowing vision unencumbered by rules and regulations of what makes “good” art.

“These are artists who are pursuing creativity because of some personal experience that provides a source of inspiration that has nothing to do with having gone to art school,” says Lynda Roscoe Hartigan, former chief curator of the SmithsonianAmericanArt Museum and now chief curator of the PeabodyEssexMuseum in Salem, Massachusetts. While some contemporary folk artists have physical or mental disabilities or difficult personal circumstances, Hartigan says there is an unfortunate tendency to assume that all such artists are divorced from everyday life. “Their inspiration is not different from fine artists. They are commenting on the world around them,” she says. “Perhaps some are expressing anxieties or beliefs through art. Others find inspiration in spiritual beliefs.”

Parked under a canopy of oaks is Chris Hubbard’s Heaven and Hell Car, influenced, he says, by his Catholic upbringing and a longtime interest in Latin American religious folk art. It’s a 1990 Honda Civic encrusted with found objects such as toys, and tin-and-wood figures he’s made of saints, angels and devils. “I wanted to bring art to the streets,” says Hubbard, 45, of Athens, Georgia, who six years ago left a 20-year career in environmental consulting and microbiology to become an artist. “I knew I had to make an art car after seeing a parade of 200 of them in Texas in 1996,” he says. The car has nearly 250,000 miles on it; he drives it 25,000 miles a year to as many as 16 art and car shows. To satisfy requests from admirers and collectors, he began selling “off the car” art—figures like the ones glued to the vehicle. Hubbard’s next art car will be Redención, a 1988 Nissan pickup truck with 130,000 miles on it. “It’s gonna be this gypsy wagon covered with rusty metal, tools and buckets and boxes,” he announces.

Across a grassy ditch, a riot of color blazes from the booth of “Miz Thang,” 47-year-old Debbie Garner from Hawkinsville, Georgia. Her foot-high cutouts of rock ’n’ roll and blues artists, ranging from B.B. King to such lesser-known musicians as Johnny Shines and Hound Dog Taylor, dangle from wire screens. Garner, a special-education teacher, is here for her third show; she finds inspiration for her blues guys in the music she loves. “I’d like to be doing this full time, but can’t while I’m putting two kids through college,” she says matter-of-factly. “Making this stuff just floats my boat and shakes my soul.” Garner’s inventory is moving too; by the end of the weekend, she’s sold most of the two hundred or so pieces she brought with her.

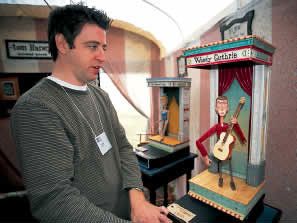

Trying to make a successful first showing, Tom Haney, 41, from Atlanta, displays his animated, articulated wooden figures in a carefully ordered booth. Intricately carved and painted, the figures move—they jump, dance and gyrate with arms flying and hats tipping, powered by a hand-cranked Victrola motor or triggered by piano-type keys. Haney says he puts in 100 or so hours on a small piece and up to 300 on the more complex figures. Which may explain his prices: while folk art at nearby booths sells for $10 to $500, Haney’s work is priced from $3,200 to $8,000. “Kentuck is the ideal place to show,” he says. “My work needs to be demonstrated face to face.” This weekend, however, he will not make a single sale; he plans to return to the festival for another try.

sunday morning the rain arrives, and tents and tarps go up over the artwork as the weekend’s music performers take their place onstage. Each year’s festival ends with a concert; this one features bluegrass legend Ralph Stanley and the Clinch Mountain Boys, rediscovered by a new generation thanks to the 2000 movie O Brother, Where Art Thou? “Kentuck really is a big ol’ party of Southern hospitality,” says artist Woodie Long. “These people drive all this way to see some good art and make friends; the least we can do is thank ’em with some good old-timey music—and hope they’ll forget about the rain.”