Food Like You’ve Never Seen Before

Molecular gastronomist Nathan Myhrvold creates culinary oddities and explores food science in his groundbreaking new anthology

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/extreme-cuisine-hamburgers-cooking-631.jpg)

Late on a rainy evening in March, the black-sweatered crowd filled the hallways of New York City’s Institute of Culinary Education. It was late because that’s when many of the guests, who toil in restaurant kitchens, got off work. They wore black because it’s the costume of the cultural avant-garde, a movement whose leadership has improbably devolved from artists, composers and writers to the people who cut up chickens. Professional chefs, long counted among the most reliable acolytes of the bourgeoisie—why else would they be so drawn to Las Vegas?—have seized the vanguard of Revolution and are carrying it out, one hors d’oeuvre at a time. At this very moment, in fact, a half dozen of them are hunched conspiratorially over bowls of mysterious white flakes, arranging them in heaps onto spoons to be passed around by waiters.

“Any hints on how to eat this?” I asked a young woman, a food stylist for a cooking magazine.

“Don’t breathe out,” she advised.

I coughed, sending a powdery white spray cascading onto my shirt front. For the rest of the evening I wore a dusting of elote, a Mexican street-food snack of corn on the cob. Except this was elote deconstructed, reimagined and assembled into an abstraction of flavors, a Cubist composition of brown butter powder, freeze-dried corn kernels and powdered lime oil. The flavors of corn and butter burst onto my tongue in an instant, and were gone just as quickly.

“It’s delicious, isn’t it?” the woman said.

“Yes, and very, uh...”

“Light?”

“Actually I was thinking it would stay on the spoon better if it was heavier.”

This party marks the moment the Revolution has been waiting for: the publication of Modernist Cuisine, the movement’s manifesto, encyclopedia and summa gastronomica, 2,438 pages of cooking history, theory, chemistry and microbiology in five oversize, lavishly illustrated volumes, plus a spiralbound book of recipes on waterproof paper, weighing 43 pounds. More than three years and roughly five tons of food in the making, it is “the most important book in the culinary arts since Escoffier,” in the opinion of the restaurant guide founder Tim Zagat—a monument to the vision of an obsessive cook, brilliant scientist and entrepreneur who is also, conveniently, extremely rich. Nathan Myhrvold, the principal author, “would be a frontrunner for a Nobel Prize in gastronomy, if they had one,” gushed the celebrity food writer Padma Lakshmi, introducing Myhrvold two nights earlier at a symposium at the New York Academy of Sciences. He is “one of the most interesting men I have ever met in my life,” she added—high praise considering that the competition includes Lakshmi’s former husband, Salman Rushdie.

Myhrvold’s round pink face is framed by a blond-going-to-gray beard, and often creased by an amused smirk, an expression he earned at the age of 14, when he was accepted to UCLA. By age 23 he had earned advanced degrees in mathematical physics, mathematical economics and geophysics and was on his way to Cambridge to study quantum gravity under Stephen Hawking. He has a scientist’s analytical, dispassionate habits of mind; when someone in the audience at his talk asks for his opinion on cannibalism, Myhrvold replies it’s probably bad for you, because people are more likely than other kinds of meat to contain parasites that afflict people.

After Cambridge, Myhrvold helped found a software company that was acquired by Microsoft—along with Myhrvold himself, who rose to the position of chief technology officer before retiring in 1999. Today, he runs a business outside Seattle called Intellectual Ventures, a technology think tank for inventions such as a laser system to identify, track and incinerate mosquitoes in flight. IV, as the firm is called, has also served as a base for Myhrvold’s culinary experiments. He was drawn to cooking from an early age, and even as a software executive spent a day a week cutting vegetables and boning ducks as an apprentice in a tony Seattle restaurant. He went on to win important awards in competitive barbecue, before falling under the spell of Ferran Adrià, the wildly creative and acclaimed Spanish chef credited with inventing a style of cooking that is known to the Food Network-watching public as “molecular gastronomy.”

Myhrvold, Adrià and other chefs reject that label as inaccurate. Besides, as a phrase to lure restaurant customers it’s not exactly up there with Steak Frites. But I think it captures Adrià’s unique perspective, his ability to transcend the inherent attributes of vegetables and cuts of meat. For most of human history, cooks took their raw ingredients as they came. A carrot was always and forever a carrot, whether it was cooked in a pan with butter or in the oven with olive oil or in a pot with beef and gravy. Modernist cooking, to use Myhrvold’s term, deconstructs the carrot, as well as the butter, olive oil and beef, into their essential qualities—of flavor, texture, color, shape, even the temperature of the prepared dish—and reassembles them in ways never before tasted, or imagined. It creates, says Myhrvold, “a world where your intuition fails you completely,” where food doesn’t look like what it is, or necessarily like food at all. One of its proudest achievements is Hot and Cold Tea—a cup of Earl Grey that by some chemical magic is hot on one side and cold on the other. “It’s a very odd feeling,” says one of Myhrvold’s two co-authors, a chef named Chris Young. “Kind of makes the hairs stand up on the back of your head.”

That’s what they said about Picasso, too, and modernist cooking represents a leap of imagination comparable to the invention of Cubism, which first allowed artists to depict the natural world from multiple perspectives on the same canvas. That breakthrough gave the world Les Demoiselles d’Avignon; this one has bequeathed unto humanity a dish called Everything Bagel, Smoked Salmon Threads, Crispy Cream Cheese, which I had as part of the tasting menu at WD-50, Wylie Dufresne’s acclaimed modernist restaurant in Manhattan. The “everything bagel” was actually a circle of bagel-flavored ice cream the size of a quarter, which illustrates another sense in which “molecular” could be applied to this style of cooking: the portion sizes, although, to be fair, a meal may comprise three dozen courses.

“Molecular” also expresses modernist cuisine’s debt to chemistry and physics, from which come the techniques and ingredients that create its intuition-shattering effects. Spun in centrifuges at 25,000 times Earth’s gravity, doused in liquid nitrogen at minus 321 degrees Fahrenheit and seared with a welder’s torch, food comes transformed into dollops of foam, blobs of gel or quivering translucent spheres. Myhrvold named his kitchen the Food Lab and equipped it with vacuum pumps, autoclaves, blast chillers, freeze dryers, ultrasonic homogenizers and industrial centrifuges. Laboratory-quality digital thermometers and scales give readings to the 10th of a degree and 100th of a gram. Baking and roasting are done in professional “combi” ovens, which control humidity as well as temperature. The pantry shelves are filled with jars labeled methocel and calcium lactate, as well as cinnamon and nutmeg—Myhrvold views the distinction some people draw between chemical and natural ingredients as sentimental nonsense. It comes almost as a surprise to see a prep cook whacking at a carrot with an actual knife. (They considered cutting vegetables with lasers, but lasers tend to burn the sugars, said Maxime Bilet, Myhrvold’s other co-author.) One thing modernism is not rebelling against is the industrialization of food. If a meal at Adrià’s world-famous restaurant, El Bulli, came with a list of ingredients, guests might be surprised to see it had more in common with a package of Pop Rocks candy than anything they might have eaten at, say, the Paris restaurant La Tour d’Argent.

Call it soulless, if you will—you won’t hurt Myhrvold’s feelings, because he knows that most of what you believe about cooking is mistaken. The delicious aroma of stock simmering on the stove that is the desideratum of home cooks? A total waste of flavor molecules, dissipating in the air instead of concentrating in the pot; his experimental kitchen is as odorless as a sterile flask. Do you sear meat quickly in a hot pan or on a grill to “seal in the juices,” as cookbook writers have been advising for generations? Well, you’re in thrall to a myth: painstaking experiments have shown just the opposite effect. How do you relate the thickness of a steak, or the weight of a turkey, to the time it takes to cook? Drawing on pioneering work by Harold McGee, author of the 1984 classic On Food and Cooking, Myhrvold gives you the formulas you need: the time required for the steak increases as the square of the thickness—a two-inch steak takes four times longer than a one-inch steak of the same size—while roasting time is proportional to the 2/3 power of its mass. Did we mention Picasso? Myhrvold’s preferred comparison is to Galileo, who showed, among other things, that comparable objects of different masses fall at the same rate, thanks to gravity. “This,” he says, “is like the paradigm shift that came in with Galileo. Before Galileo, people thought heavier objects fell faster. The world of food has been living until now in the pre-Galilean universe.”

Myhrvold’s interest in modernist cooking began when he bit into a piece of meat that had been prepared by a technique known as sous vide. This involves sealing raw food in a vacuum pouch and immersing it in a circulating warm-water bath until it’s cooked through. Sous vide solves a problem cooks have faced since the invention of fire—namely, how to achieve a uniform temperature through a whole piece of meat. To cook a steak to 130 degrees we throw it on a 500-degree grill and wait for the heat to penetrate to the center. It’s easy to get wrong—the time window for removing it can be a matter of seconds. “If you went into a steak restaurant kitchen today,” Myhrvold says, over a pre-Galilean lunch of veal cheeks and polenta at a Manhattan restaurant, “you’d see the grill cook with 20 steaks and he’s testing each one of them continuously to know the exact moment to take it off the heat. It turns out that people are not very good at this.”

Instead, why not just dial in the desired temperature on a sous-vide machine and wait until the meat is cooked through to a uniform, precisely controlled degree of doneness? Well, one reason is that the process can take a long time; Myhrvold has one recipe, for oxtail, that calls for 100 hours of cooking. Another reason is that people generally prefer their steaks browned and their chicken skin crisp, though that problem is easily solved with a welding torch. The color of the resulting beef, an unnervingly uniform maroon from edge to edge, and the texture, more like very firm tofu than anything that once walked on four legs, may take some getting used to. But the logic and precision of the technique appealed to Myhrvold far more than the reactionary ideal of the maestro who cooks by sizzle and intuition. He began to seek more information, but there was hardly any to be found; almost no one had written about sous vide, at least not in English.

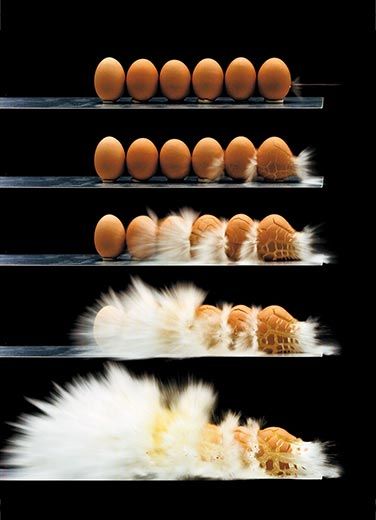

So Myhrvold began running his own experiments at home and posting the results online. Out of this grew the idea for a book, and the hiring of a crew including Young, Bilet and numerous assistants. The project kept growing. You can’t talk about sous vide, Myhrvold realized, without explaining why eating a piece of meat that spent 72 hours in a warm-water bath won’t send you straight to the emergency room. (The key is keeping the temperature just hot enough to kill food-borne bacteria—something, he notes, that most municipal health departments refused to believe the first time they encountered it in a kitchen under their jurisdiction). So a chapter was added on microbiology, in which Myhrvold informs readers they’ve been worrying about all the wrong things, incinerating their pork chops to kill the parasite that causes trichinosis, a virtually nonexistent threat today in well-developed countries, while ignoring the much greater threat of fresh vegetables contaminated with pathogenic strains of E. coli bacteria. Furthermore, to put sous vide in context would require the equivalent of an entire book on traditional cooking, so he set out to write one. Wanting beautiful pictures, Myhrvold acknowledged that plastic bags in a tub of hot water make for singularly uninteresting tableaux. With a machine shop at his disposal, he took to cutting bowls, pots and other cooking utensils down the middle to indulge his passion for cross-section photographs. It’s not easy to cook in half a wok, and his experiments had a disconcerting tendency to burst into flames as oil splashed onto the burners—but, as Myhrvold reassured his photographer, Ryan Matthew Smith, the great thing about still photography is things only have to look good for a thousandth of a second.

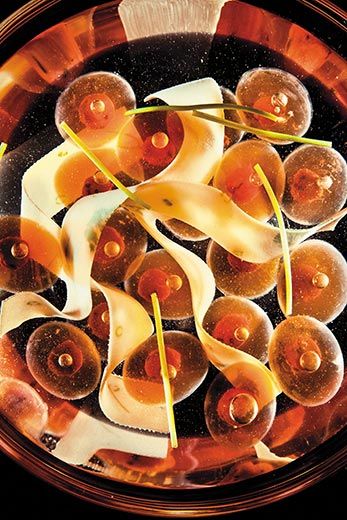

And then Myhrvold got interested in gels, foams and spheres, to which modernist chefs have a deep, inexplicable attachment. Among the substances that Myhrvold recommends spherifying are melon juice, capers, mussels, Gruyère cheese and olives. To someone not steeped in the modernist aesthetic, it may not be obvious why you should purée a batch of olives and follow a 20-step recipe calling for xanthan gum and sodium alginate to produce essentially what you started with, a round object that tastes like an olive.

To find out would involve a trip to El Bulli, but the restaurant received around two million requests last year for dinner at one of its 15 tables, and it’s scheduled to close permanently next month anyway, so you might want to try the instructions in Myhrvold’s book. If you own an industrial centrifuge and don’t mind leaving the kitchen for an hour while it runs, in case it flies apart with the force of a small bomb, you can see what comes out when you spin frozen green peas at 40,000 times Earth’s gravitational force. You will find a starchy gray-green sludge at the bottom, clear pea-juice on top, and between them a thin layer of a rich, buttery, brilliantly green pea-flavored substance that can be spread on a cracker to make a fine canapé. And the next thing you know, you’re boiling grated Parmesan cheese and water and pressing it out through a sieve and squirting it into plastic tubing to make Parmesan noodles. If you’re really committed to modernism, you could freeze-dry pasta and grate it on top.

It may have occurred to you that this kind of cooking runs exactly counter to the other dominant trend in dining, the quest for authenticity, traditional preparations and local ingredients that sometimes goes by the name “slow food.” Among its most eloquent advocates is the author Michael Pollan (In Defense of Food), whose motto is “don’t eat anything your great-grandmother wouldn’t recognize as food.” Yet even Pollan was won over by his lunch at the Food Lab, pronouncing the sous-vide short-rib pastrami, a signature dish, “pretty incredible. It’s a realm of experimentation, of avant-garde art. There’s art I find incredibly stimulating, but I wouldn’t necessarily want it on my living-room wall.” For his part, Myhrvold regards Pollan with mild condescension, implying that he has failed to think through his own philosophy. “If everyone had followed his rule about great-grandmothers, recursively back into history, nobody would ever have tried anything new,” Myhrvold says. “Many of the things the slow food people honor were innovations within historical times. Somebody had to be the first European to eat a tomato.”

Yes, and somebody had to be the first person to make a six-foot-long Parmesan noodle, and since I had obtained one of the first copies of Myhrvold’s book, I thought it should be me. I would accompany the noodle dish, I decided, with Myhrvold’s recipe for spherified tomato water with basil oil. In the photographs, these were shimmering, transparent spheres, each trapping within it a bright-green globe of liquid pesto. I could hardly wait to try one.

Right off the bat, though, I faced my limitations as a home cook. Lacking a centrifuge to produce the colorless tomato-flavored liquid the recipe demands, I had to rely on the relatively crude technique of vacuum filtration. Not that I had a machine for that either, but I managed to improvise one with a medical suction device and a coffee filter, which produced, at the rate of about three droplets a minute, a small quantity of slightly cloudy, rose-colored liquid. Also, the brand of agar Myhrvold specifies for the noodles sells for as much as $108 for half a kilogram, which seemed extravagant since the recipe called for only 2.1 grams. Even that amount would make 90 linear feet of noodle. I cut the recipe by three-quarters, and in the process of pouring the mixtures in and out of saucepans and measuring cups, straining and sieving, an awful lot got left behind. In the end I managed to fill just one and a half six-foot lengths of quarter-inch-diameter plastic tubing, which had to be submerged in ice water for two minutes and quickly attached by one end to a soda siphon. Then with one quick burst of carbon dioxide the contents came shooting out in glorious, shimmering heaps that served six people, as long as they were content with three mouthfuls each. I considered this a triumph, especially compared with the tomato spheres, which turned into shapeless, drippy blobs that fell apart as soon as I dunked them in the three bowls of ice water specified by Myhrvold’s recipe.

But everyone was complimentary, and I’m pleased to have played my part in this great culinary revolution. Adrià himself would have understood my impulse to then boil up a large pot of spaghetti and defrost a container of marinara sauce that had been in the freezer since August. As his biographer, Colman Andrews, reports, when Adrià goes out to eat, his favorite meal is fried calamari, sauteed cuttlefish with garlic and parsley, and rice with seafood. In other words, he eats what his great-grandmother would recognize.

Jerry Adler last wrote for Smithsonian about Depression-era art. He says he eats whatever is put in front of him.