The Forgotten Dust Bowl Novel That Rivaled “The Grapes of Wrath”

Sanora Babb wrote about a family devastated by the Dust Bowl, but she lost her shot at stardom when John Steinbeck beat her to the punch

:focal(328x165:329x166)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3d/37/3d374f93-720d-46e8-9ba3-a53662781b4d/p_hrc-p_bab_1211.jpg)

When The Grapes of Wrath came out 77 years ago, it was an instant hit. The story of a destitute family fleeing the Dust Bowl sold 430,000 copies in a year and catapulted John Steinbeck to literary greatness. But it also stopped the publication of another novel, silencing the voice of an author more intimately connected to the plight of Oklahoma migrants because she was one herself.

Sanora Babb wrote Whose Names Are Unknown at the same time Steinbeck wrote The Grapes of Wrath, using much of the same research material. While both novels are about displaced farmers coming to California, they’re very different books. Babb’s novel is a carefully observed portrayal of several families that draws on her Oklahoma childhood. Steinbeck’s work, considered his masterpiece by many, is a sweeping novel bursting with metaphor and imagery. In many ways, the books are complementary takes on the same subject: one book is spare and detailed, the other is big and ambitious. One spends more time in Oklahoma, the other spends more time in California. One focuses on individual characters, the other attempts to tell a broader story about America. Liking one novel over the other is a matter of taste; Sanora Babb, as is natural, preferred her own work.

"I think I'm a better writer," Babb told the Chicago Tribune in 2004. "His book is not as realistic as mine."

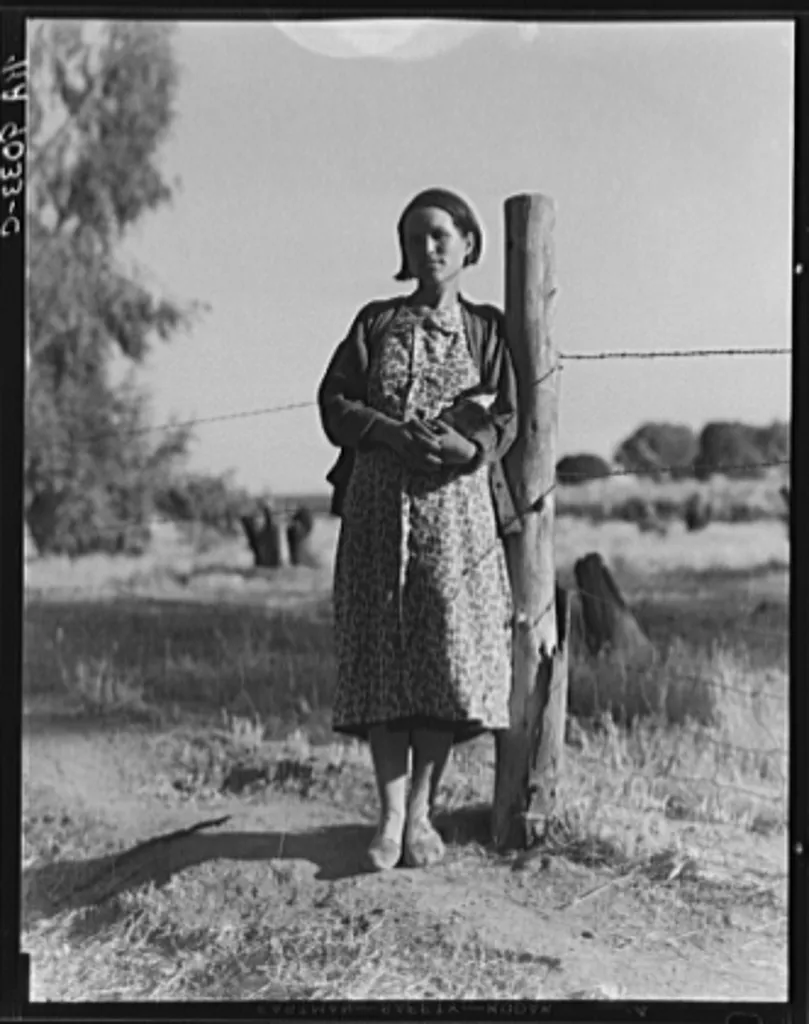

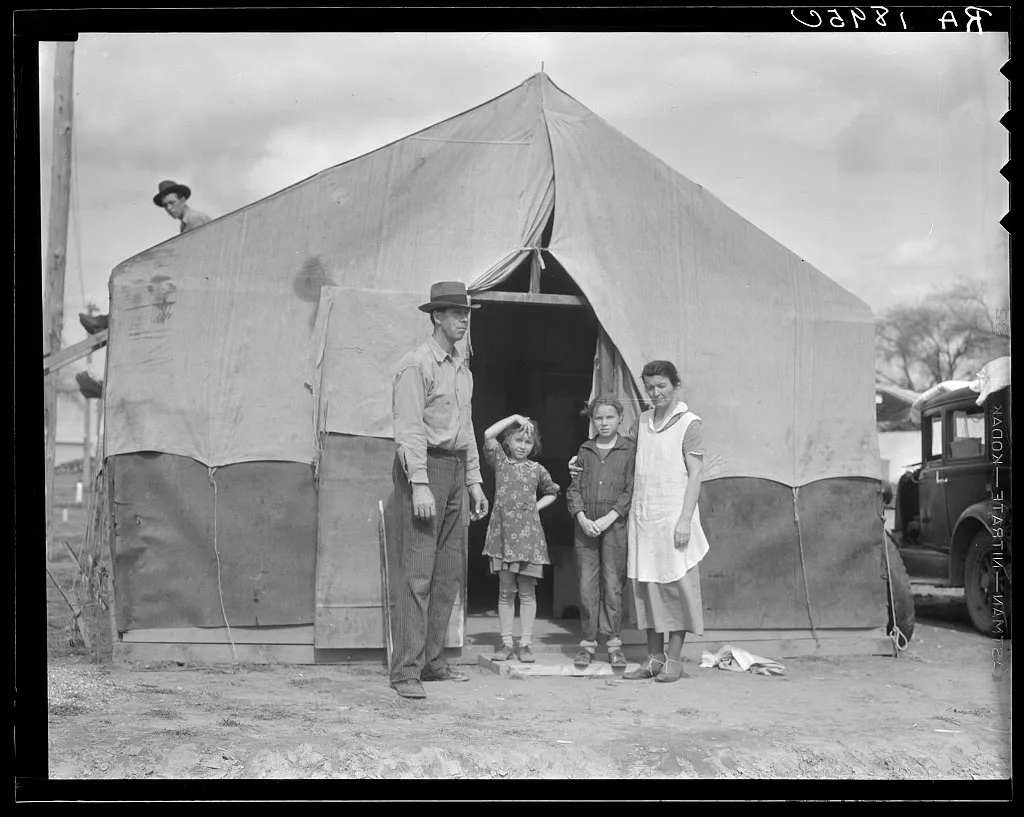

In 1938, Babb, a 31-year-old editor and writer, volunteered with the Farm Security Administration (FSA) to help migrant farmers flooding into California. As assistant to Tom Collins, manager of Arvin Sanitary Camp (the basis for Weedpatch in The Grapes of Wrath), Babb traveled the Central Valley, working with the migrants and setting up better living conditions. She was struck by the resilience of the workers she met, writing to her sister: “How brave they all are. I have not heard one complaint! They aren’t broken and docile but they don’t complain.”

Part of her job was to write field notes on the workers’ conditions, detailing activities, diets, entertainment, speech, beliefs and other observations that were natural fodder for a novel. Soon, Babb began writing one. She based her story on what she’d seen in the camps as well as her own experience. The daughter of a restless gambler, she was born in Oklahoma territory in 1907. The family moved around to Kansas and Colorado before returning to Oklahoma when Babb was in high school. (Babb was valedictorian of her class, although "the gambler's daughter" was barred from giving a speech at graduation.) She witnessed a major dust storm while visiting her mother in 1934 and heard what the crisis did to farmers she’d known as a child.

She also understood what it was like to be destitute. In 1929, she moved to Los Angeles to become a reporter, only to discover that work had dried up with the stock market crash. For a time, she was homeless and forced to sleep in a public park until she was hired as a secretary for Warner Brothers. Later, she got a job as a scriptwriter for a radio station.

All this, plus the notes she took while visiting the camps, went into Whose Names Are Unknown. In 1939, Babb sent four chapters to Bennett Cerf, an editor at Random House, who recognized her talent and offered to publish the book. Babb was ecstatic. What she didn’t know, however, was that Collins had given her notes to Steinbeck, who was busy researching The Grapes of Wrath.

The two men met in 1936 when Steinbeck was hired by the San Francisco News to write a series of articles about the migrants titled “The Harvest Gypsies.” The articles were later reprinted by the Simon J. Lubin Society in a pamphlet alongside Dorothea Lange’s iconic photographs to help the public understand the severity of the crisis.

“Steinbeck knew the minute he wrote those articles in 1936 that he had a novel,” says Susan Shillinglaw, Steinbeck scholar and interim director of the National Steinbeck Center. “He called it his Big Book. He knew he had a great story—writers know that. So the fact that Babb wanted to write about the same thing is not surprising. It was an important American story.”

In the following years, Steinbeck took several trips to the Central Valley to research the novel, spending time in the camps and interviewing the migrants. Collins, who played a major role in setting up government camps throughout the Central Valley, was eager to help. The two men struck a deal. Collins would give Steinbeck government reports, travel with him to the camps, and introduce him to workers who might be of interest. In return, once The Grapes of Wrath was finished, Steinbeck would help edit Collins’ nonfiction book on the crisis. (Although Steinbeck introduced Collins to publishing professionals, the book never materialized.) Collins’s help was so essential to the development of The Grapes of Wrath that Steinbeck dedicated the book to him.

Among the research Collins passed his way were meticulous FSA reports, which covered everything from what the migrants ate to what they wore to how they spoke. Babb contributed to some of these reports, and also took field notes for Collins. Some of this—it’s unclear exactly what—was passed onto Steinbeck.

“Babb was a writer before she volunteered with the FSA, and it was in her nature to be recording and writing stories of the farmers,” says Joanne Dearcopp, literary executor of the Sanora Babb estate. “Because she worked alongside the workers and helped organize the camps, she also wrote field notes and contributed to the FSA reports that Tom had to submit..”

While Babb was working on Whose Names Are Unknown, Steinbeck sped through writing The Grapes of Wrath in an astounding six months time. The book was released on April 14, 1939. In the ensuing weeks and months, it would become the best-selling book of the year, win the Pulitzer Prize, and be adapted into a successful film by director John Ford. Cerf responded by shelving Whose Names Were Unknown. In a letter to Babb, he wrote, "Obviously, another book at this time about exactly the same subject would be a sad anticlimax!" She sent the manuscript to other publishers, but they too rejected it. Aside from the fact that many of these editors were Steinbeck’s personal friends, to publish her novel after a hit like The Grapes of Wrath would look like imitation.

Babb, of course, was upset by this turn of events. Although Cerf offered to publish another book, her confidence appears to have waned. She put off writing books for 20 years until, in 1958, she published The Lost Traveler. In between, she wrote short stories and poems, worked as editor for publications like The Clipper, and cultivated friendships with writers including Ray Bradbury and William Saroyan. There was a brief affair with Ralph Ellison. She also fell in love with James Wong Howe, an Oscar-winning, Chinese-American cinematographer who worked on The Thin Man, The Old Man and the Sea, Funny Lady, and others. They had to postpone marriage until California’s ban on interracial marriage was lifted in 1948; they remained together until Howe’s death in 1976.

Babb went on to write several other books, including the memoir An Owl on Every Post, but Whose Names Are Unknown, the book that could have cemented her status as a Depression-era writer like Steinbeck or Upton Sinclair, remained in a drawer. Finally, in 2004, University of Oklahoma Press published the novel; Babb was 97 years old.

All this raises the question: did Steinbeck know that he was in possession of notes drafted by a fellow writer? Most likely not.

"We have no proof that Steinbeck used her notes," says Dearcopp. "We know her notes were given to him, but we don't know whether it was in the form of a FSA report of not. If that's the case, he wouldn't have known they came from her specifically. So we can't know to what degree he used her notes, or didn't, but at the end of the day, she was in the fields working with the migrants. She was the one doing that."

Shillinglaw, who's firmly on Team Steinbeck, disagrees. “The idea that Steinbeck used Babb’s notes undercuts the fact that he did his own research by going to the fields since 1936, as well as using Tom Collins’s research,” she says. “What could Babb add to that? I don’t know.”

While the two books differ in story and tone, their common background leads to odd similarities. For example, both novels have stillborn babies in them. Babb’s baby is described as “curled up, wrinkled and queer looking” while Steinbeck’s baby is a “blue shriveled little mummy.” They both describe the corruption of corporate farms, high prices at company stores, women giving birth in tents, and small creatures struggling against the landscape, Babb’s insect and Steinbeck’s turtle. And both writers based characters on Tom Collins.

Steinbeck’s working journals for The Grapes of Wrath show a man consumed with producing a work of art, a task that drove and intimidated him. “If only I could do this book properly it would be one of the really fine books and a truly American book,” he wrote. “But I’m assailed with my own ignorance and inability.”

With thoughts like this hounding him, Babb probably wasn’t in his mind at all, even though she later said he met her twice while researching the novel. Her situation was the result of bad timing and the sexism of her age—the famous man’s important work squashed the attempts of the unknown woman writer.

Babb died a year after Whose Names Are Unknown was published, knowing that her first novel would be read at last, 65 years after she wrote it.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/bd/3b/bd3b1aba-6741-490a-9ce6-3364b41aeae2/8b31828v.jpg)