Hangovers: The Driving Force Behind Our Favorite Foods

Overimbibing makes some people’s brains shut down, for others, it gets the innovative juices flowing

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20130719085058thumbimage_hangoverblog1.jpg)

It’s hard to imagine anything positive coming out of the dreaded hangover, that ultimate punishment doled out by the universe in the form of headaches, nausea and general discomfort. After a night of revelry, the unlucky afflicted often retreat to their beds, nursing aches and pains with rest and water. A brave few, however, have surged ahead, grasping at a mix of science and migraine-induced cravings to create their own remedies for the infamous day-after-blues. While some of these inventive cures have failed the test of time (deep-fried canary was a favorite of the Romans which, thankfully, you won’t find on your nearest diner menu), others have reached a level of success so mainstream that you might be surprised by their more nefarious origins.

Brunch: Though currently a popular venue for weekend gossip and day drinking, this portmanteau-meal actually began as a hangover cure. Before English writer Guy Beringer proposed the most ingenious combination of breakfast and lunch, weekend feasting was strictly reserved for the early Sunday dinner, where heavy fare like meat and pies were served to the after-church crowd. Instead of forcing this early dinner, Beringer argued that life would be happier for all if a new meal was created, “served around noon, that starts with tea or coffee, marmalade and other breakfast fixtures before moving along to the heavier fare.” By letting people sleep in on Sundays, and awake later for a meal, Beringer noted that life would be made easier for “Saturday night carousers.” Beyond the appeal of a nice, substantial meal after a night of debauchery, Beringer testified to the soothing social interaction brunch brings, reasoning that it helped to “sweep away the cobwebs of the weekend.” Brunch didn’t gain traction with the American crowd, however, until the 1920s and into the 1930s, when celebrities and socialites hosted brunch parties in their homes. Brunch received an even larger following in the 70s and 80s, when church attendance dropped nationwide, and Americans swapped their religious dedication to breaking bread with the secular tradition of breaking yolks.

The Bloody Mary: Battling a hangover with more drinking has been around as a cure since alcohol itself. Famously referred to as “hair of the dog” (which actually comes from an old cure for rabies, wherein the afflicted would rub a bit of dog hair into the wound) the hungover have often turned to libations as a way to ease their pain. Perhaps no iteration of this is more famous than the Bloody Mary, ubiquitous on brunch menus (see above). But the drink itself wasn’t created to cause hangovers – instead, it was created to cure them. As bartender Josh Krist explains, the roaring crowd of ex-pats that populated Paris in the 1920s required a drink that could ease the pain from their The Sun Also Rises-esque gallivanting of the night before. In response to such demand, Fernand Petiot, bartender at Harry’s New York Bar in Paris, first created the concoction by adding equal parts vodka and tomato juice. In terms of scientific hangover cures, the one half of the libation is fairly ingenious, because tomato juice contains high amounts of both lycopene and potassium, which help stimulate blood flow and replenish electrolytes (hair of the dog, however, has been debunked as a healthy way to hurdle the hangover slump).

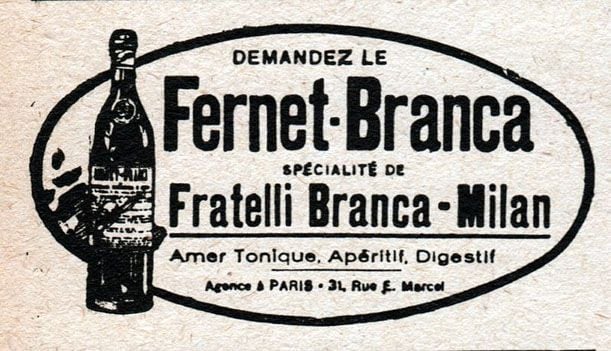

Fernet: Continuing the fine tradition of spirits invented to cure an over-indulgence in spirits (again, see above) Fernet, a famous Italian liquor now used as a post-meal digestive, was actually created for curing hangovers. As the story goes, Italian spice trader Bernadino Branca invented the spirit in 1845, adding the traditional hangover cure-all myrrh to a lot of grape infused spirits. He then added a plethora of other flavorings and ingredients, including rhubarb, chamomile, aloe, cardamom, peppermint oil, and – get this – opiates. The resulting mix certainly succeeding in perking drinkers up after a night on the town and, in much more extreme cases, patients suffering from cholera.

Eggs Benedict: If we are sensing a trend here, it’s that the world of brunch is very meta (a hangover cure that inspired other hangover cures…like some headache-ridden version of Groundhog Day). We’ve all heard of the greasy breakfast – eggs, bacon, whatever your heaving stomach can handle – as a cure for the hangover, but if you thought of eggs Benedict as too highbrow to constitute the classic “greasy breakfast,” think again: lore surrounding the origin of this famous brunch food actually cites one seriously hungover Wall Street worker as the original Benedict. In 1942, The New Yorker published an article claiming the dish had its roots in a man named Lemuel Benedict, a Wall Street worker known for his eccentric-for-the-time lifestyle choices (like marrying a woman who worked as an opera singer) and heavy partying habits. After one especially raucous night of partying, Lemuel awoke in the morning and went to breakfast at the Waldorf Hotel, where he invented his own breakfast sandwich of two poached eggs, bacon, buttered toast, and a pitcher of hollandaise sauce. Lemuel’s inventive sandwich caught the eye of the Waldorf’s famous maître d’hôtel Oscar, who sampled the sandwich, made some personal alterations (ham was swapped for bacon, an English muffin for the toast), put the sandwich on the menu, and sailed peacefully into history, much to the delight of hungover brunch attendees everywhere.

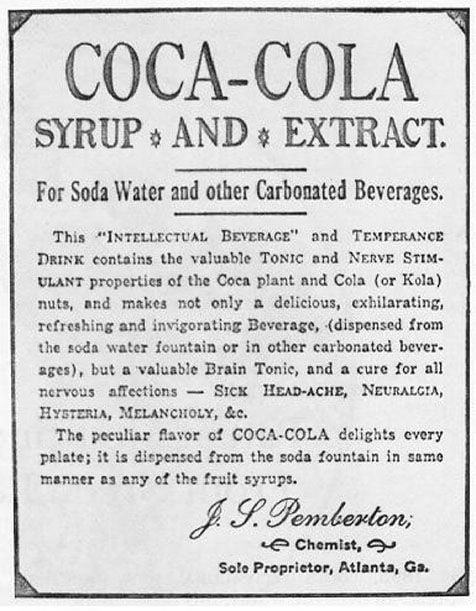

Coca-Cola: Brunch, eggs Benedict, Bloody Marys – these items are already so associated with post-drinking maladies that their origin in the history of hangovers might not come as a huge surprise. But that ever-present Coca-Cola bottle in the vending machine and corner stores, it too was a brainchild of those looking to cure hangovers. Coca-Cola went public in 1886, but the recipe that the popular beverage was based off of had been popular for years at pharmacist John Pemberton’s Atlanta drugstore and soda fountain. By mixing caffeine from cola nuts with cocaine from coca leaves, and adding a thick syrupy base, Pemberton’s original cola sold widely as a miracle hangover remedy. Soon, the beverage’s enjoyable taste made it popular with a non-drinking crowd, and Coca-Cola erupted into the famous soda we know today.