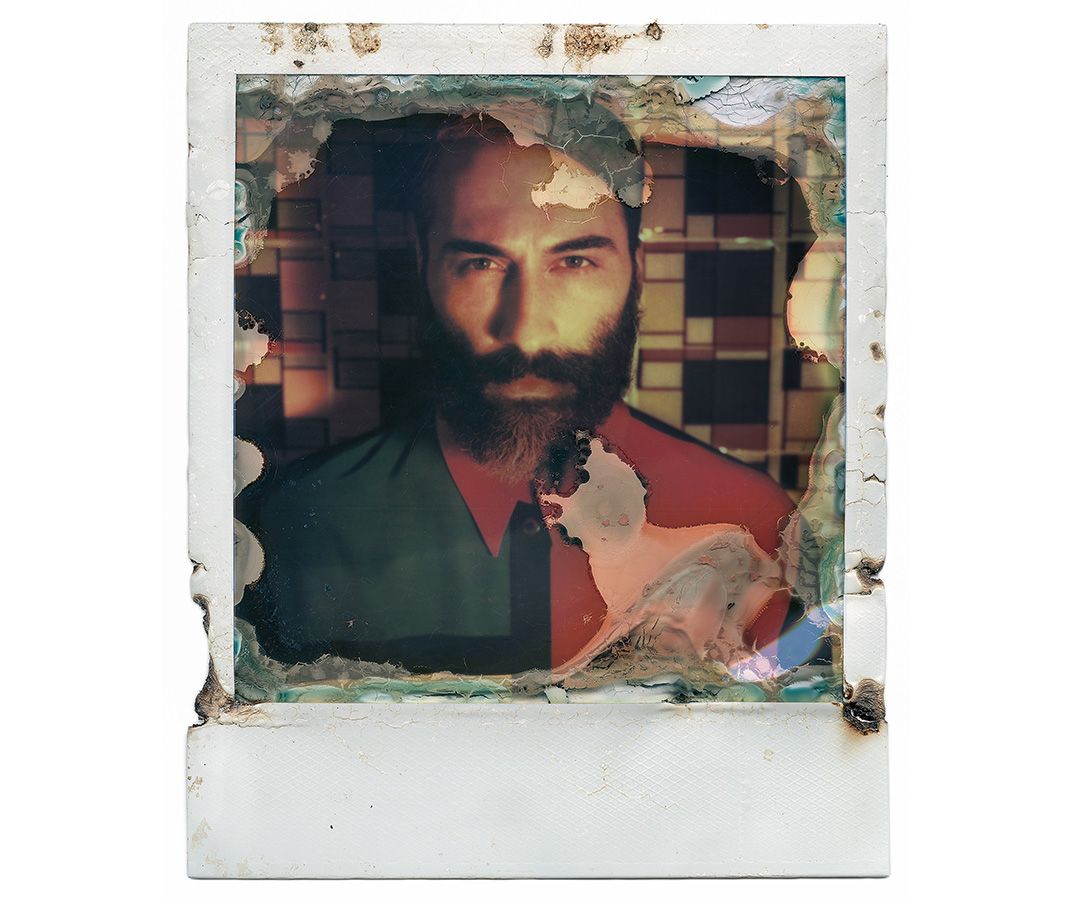

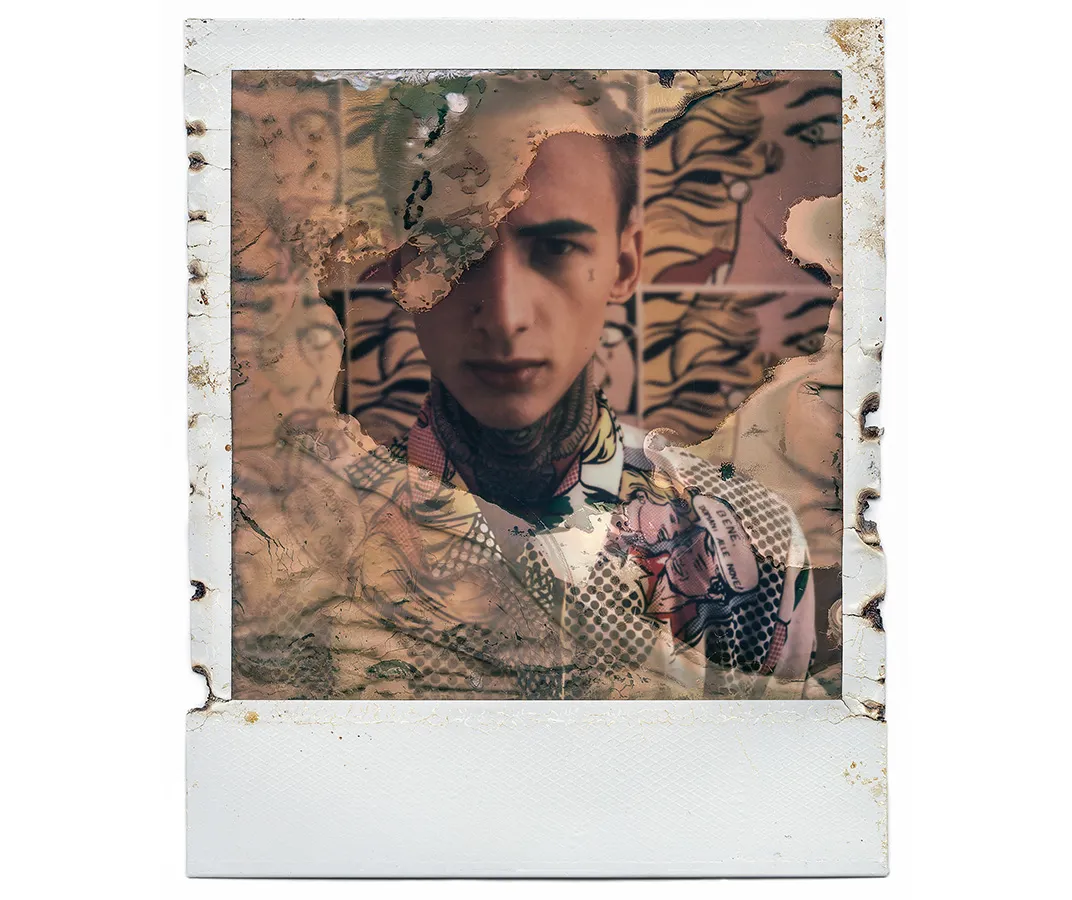

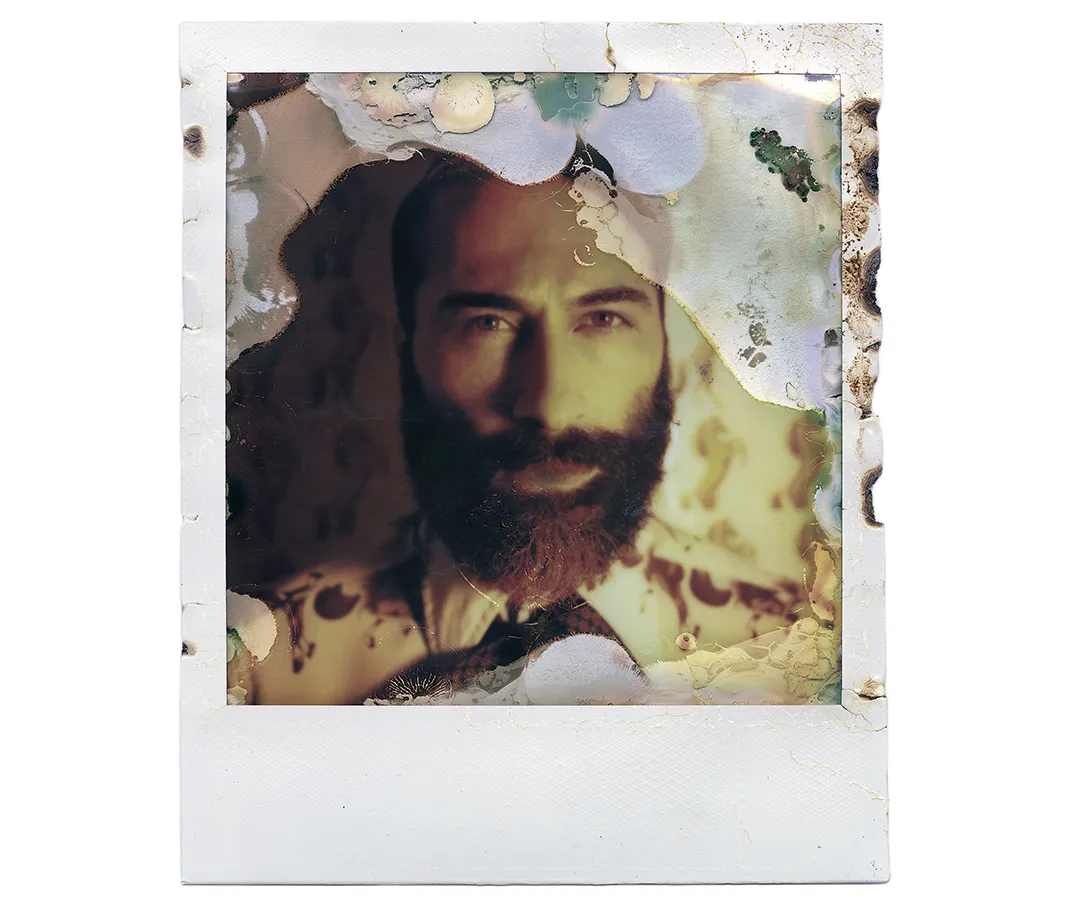

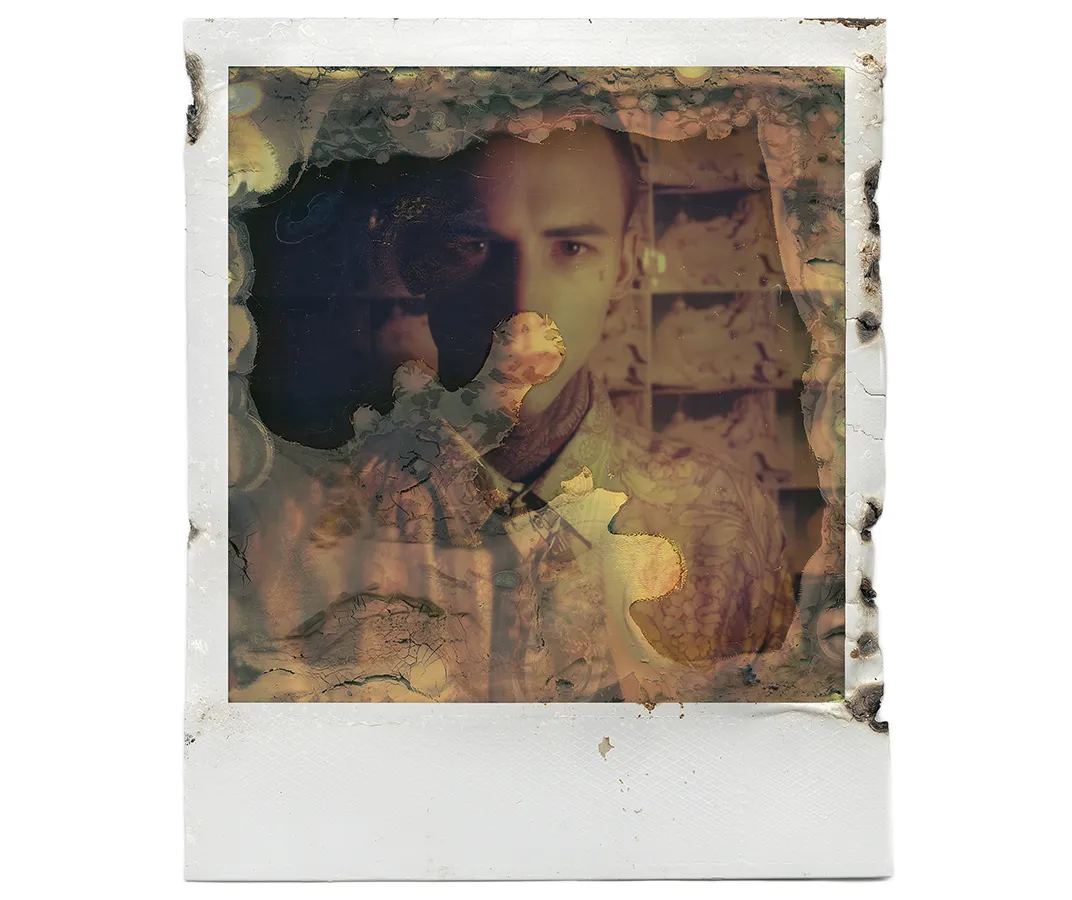

Here’s What Happens When You Put Instant Film in a Microwave

A German photographer made a name for himself by treating his photos like last night’s leftovers

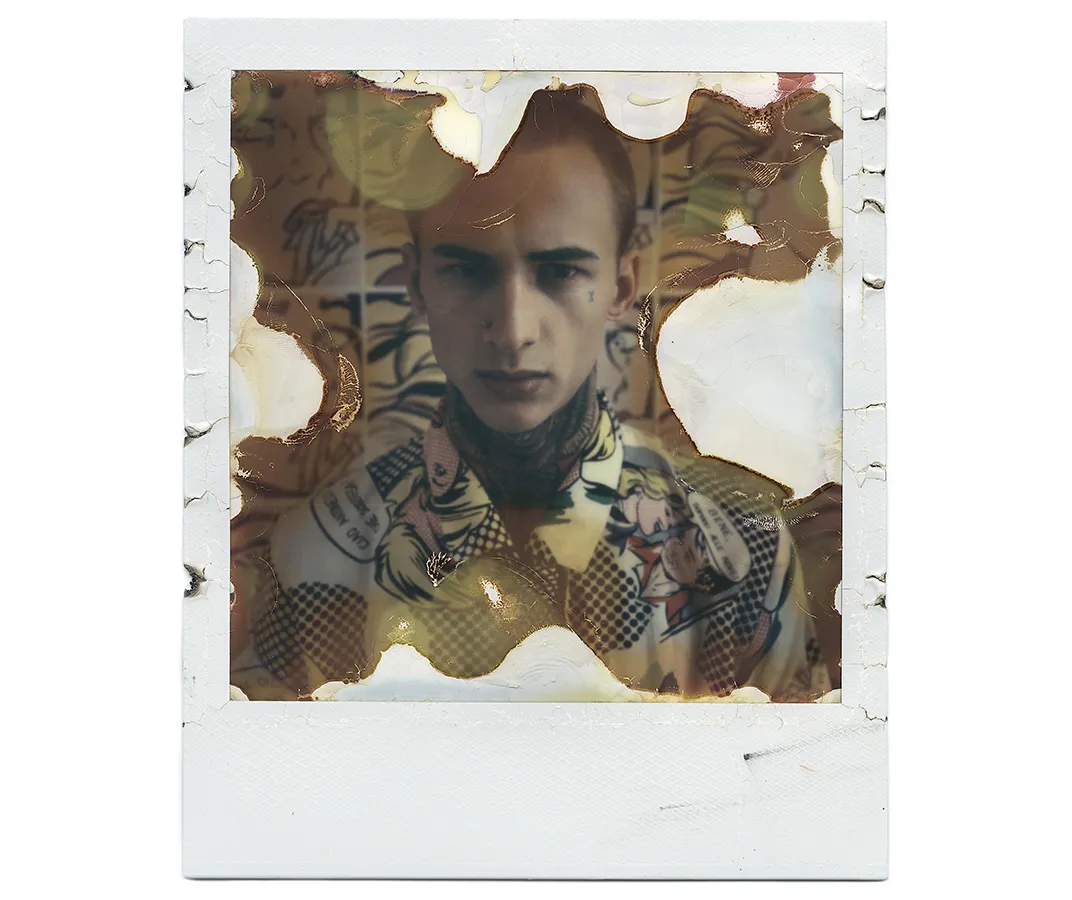

Oliver Blohm and a friend were snapping instant photos at a Berlin beer garden when they had an idea. What if they burned the photos with lighters as they developed? Their experiment wasn’t entirely frivolous, though they had consumed a good amount of Berliner Weisse. They knew the chemistry behind photography and that applying heat would alter the development process. Sure enough, the lighters created unique textures and spots on the photos and left them curious.

Over the next few weeks, Blohm, a 26-year-old photography student from northern Germany, continued experimenting. Instead of lighters, he used his flatmate’s microwave oven. After some trial and error and nervous questions from his flatmate, Blohm had perfected the method.

“This is how Oliver works,” says his friend from the beer garden, Michael Fischer. “First he has a spark in his mind and one or two months later he has this great idea.”

They trick was protecting the images from getting too hot and bursting into flames, which Blohm accomplished by inserting them between thick paper and a layer of glass. The resulting prints were beautifully discolored and warped. “It’s about the destruction,” Blohm says. “I wanted to play more and more with the texture, with the burns, with the flares.”

The film he used came from The Impossible Project, a startup that has been creating new instant film for old Polaroid cameras. Polaroid discontinued its film in 2008.

“There’s a history of people manipulating instant prints,” says Brenda Bernier, chief conservator at Harvard’s Weissman Preservation Center. Products like those sold by Polaroid and The Impossible Project are easy to manipulate because they contain complex layers of dyes and chemicals. “They are a technological marvel,” she says. “It’s essentially it’s own dark room.”

Blohm isn’t concerned about the dangers associated with his method. “Photographic processes, the coolest from the old times, are mostly dangerous and poisonous,” he says. For daguerreotypes, popular in the mid-1800s, photographers had to heat up mercury. The collodion photography process from around that time produced dangerous vapors.

The science behind Blohm’s method is simple, according to Philip Sadler, director of the Science Education Department at Harvard. “Whenever you speed things up, things become uneven,” he says. “You get different colors, you get burns, discoloration.”

James Foley, who worked at Polaroid as a chemist during the heyday of instant film, says they designed the material inside the film to react at a certain time. “By heating this up,” he says, “you could release things before all of the photographic chemistry was done,” resulting in those artistic flaws.

Earlier this year, Blohm went pro with his microwave photos. He hired models, who sat there as he dashed over to the microwave and worked his magic. Blohm titled the series “Hatzfrass,” his German translation for “fast food.” When The Impossible Project opened a store in Berlin, they invited him to exhibit the series. He even brought a microwave so he could nuke other people’s photos. Since then, “Hatzfrass” has gained the attention of bloggers. Some fans have even sent him their own microwaved images. Still, amateur photographers might want to play it safe. “It’s not gonna go nuclear,” says Ken Foster, a bioengineering professor at the University of Pennsylvania, “but you might need to have a fire extinguisher handy.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/MAx2.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/82/37/823711ab-7a5e-4acf-bef2-150eb65d845b/microwave-polaroid-9.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/07/de/07de1987-d0f7-4e49-bd50-f2c3dd295c98/microwave-polaroid-7.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b1/5e/b15efad1-0aba-4632-853c-4577a4ee1ff0/microwave-polaroid-10.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9e/54/9e542b04-e06b-475a-80d1-081e8183a137/microwave-polaroid-8.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/61/fd/61fda843-dd18-45d5-a592-7bf61809b2f4/microwave-polaroid-6.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/MAx2.jpg)