How His’n’Her Ponchos Became A Thing: A History Of Unisex Fashion

“Unisex” was rarely used before the fashion trend hit it big in the late 1960s

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e9/fb/e9fbc9cc-26de-4d03-bb02-0ecd560973a3/unisex-resize-3.jpg)

At this year’s Coachella music festival 16-year-old Jaden Smith, the scion of Hollywood royalty Will Smith and Jada Pinkett-Smith, wore a floral-print tunic and a rose-flower crown. The pairing is so standard it's a festival cliché, yet Jaden's outfit made waves online. First, because he's a celebrity in his own right, and second, because he's a boy. "Coolest of cool teens Jaden Smith sails far beyond gender norms," gushed Racked. "Who Wore it Better? Jaden Smith vs. Paris Hilton" quipped TMZ.

There was a time when such an ensemble wouldn’t have turned so many heads. Between 1965 and 1975, gender bending infiltrated American life as part of a movement called "unisex." As Jo Paoletti writes in a new book, Sex and Unisex: Fashion, Feminism, and the Sexual Revolution, the term was first used in the mid-'60s to describe salons catering to girls and guys who wanted similar haircuts—long and unkempt. By the mid '70s, it was a social phenomenon, creeping up in debates about childrearing, the workplace, military conscription and yes, bathrooms.

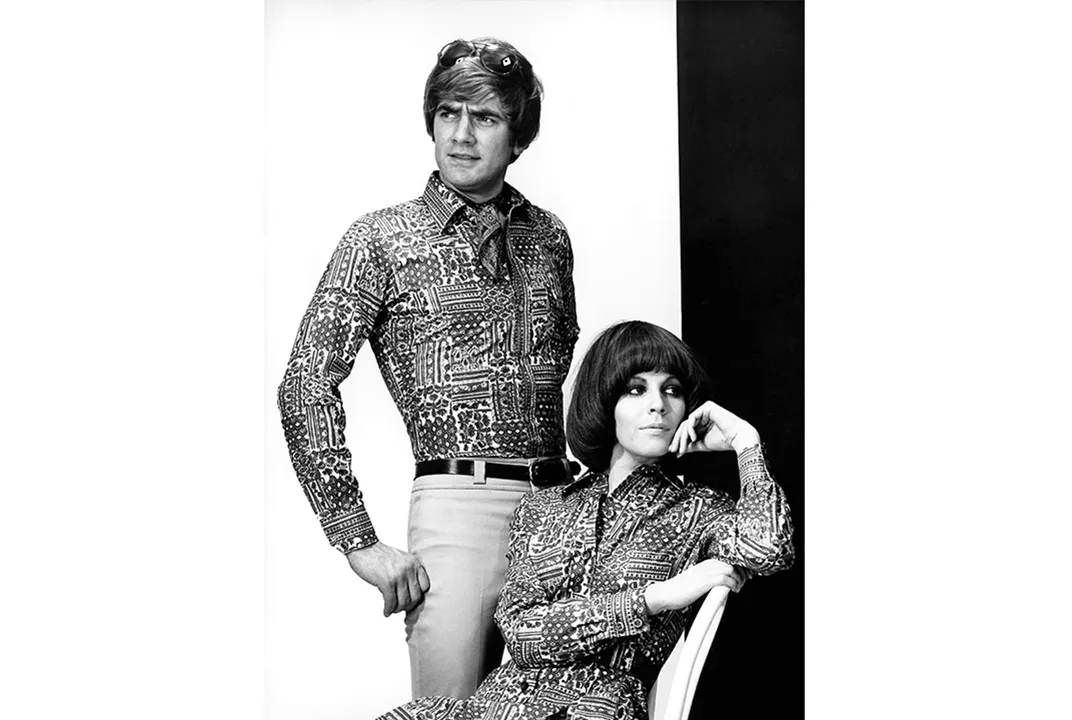

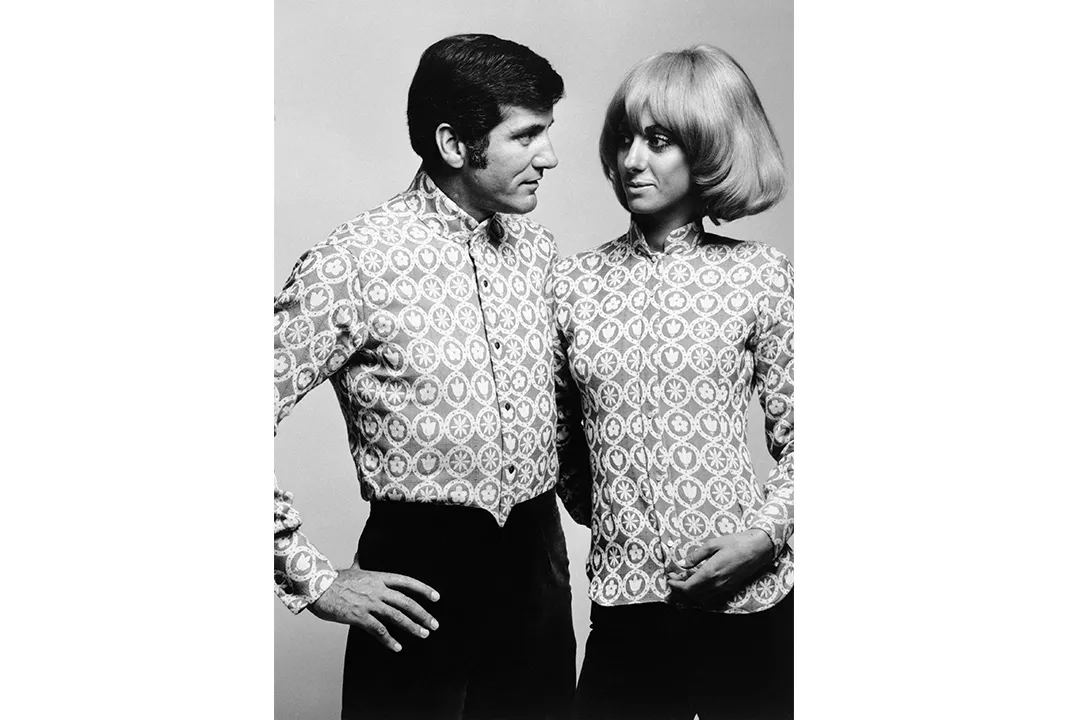

Fashion is what got it there. The New York Times first used the word “unisex” in a 1968 story about chunky “Monster” shoes, and it came up five more times before the year was over. Department stores and catalogs created new sections of his’n’her clothing, advertised by couples in matching lace bell-bottoms and burnt-orange button downs. In 1968, one Chicago Tribune columnist described a common predicament in the “age of unisex”: "'Is it a boy or a girl?' Are you inquiring about a new born child? You are not. You are asking your wife to declare the sex of the unidentified object passing a few feet in front of you. She doesn't know either."

Unisex wasn't just about confusing old people, though. As Paoletti explains, it came to act as a catch-all for various movements that broke with traditional feminine and masculine styles. For instance, during the "peacock revolution" of the late '60s, men wore Edwardian shirts and tight pants in flamboyant patterns and colors. Also in that decade, designer Rudi Gernreich created futuristic, androgynous styles like a topless bathing suit for women and “No-Bra Bras” without underwire or padding. In the '70s, unisex clothing took the form of matching patchwork denim sets and fleece "loungewear" for the whole family.

Look at old catalog photos of happy families in coordinated separates, and you'll start to understand how unisex made the leap from fashion to childrearing debates. In the early '70s, ungendered parenting became a hot topic among progressive families. Abandoning pink and blue, many thought, could quash sexism in children before it took hold. "X: A Fabulous Child's Story," published in Ms. in 1972, tells of a baby whose parents keep its sex a secret from the world. As X grows up and attends school, rather than becoming an outcast, it becomes a role model: “Susie, who sat next to X in class, suddenly refused to wear pink dresses to school anymore... Jim, the class football nut, started wheeling his little sister's doll carriage around the football field.”

Ultimately, Paoletti interprets unisex fashion as a reflection of political and social upheaval. As the feminist movement gained steam and women fought for equal rights, their clothing became more androgynous. Men, meanwhile, discarded grey flannel suits—and the restrictive version of masculinity that came with them—by appropriating feminine garments. Both genders, she argues, were questioning the idea of gender as fixed. This didn't unfold without controversy. The era saw a litany of lawsuits around institutional dress codes, including 73 on the issue of long hair on boys between 1965 and 1978. In liberal states like Vermont, courts tended to rule in favor of students, while in states like Alabama and Texas, they sided with schools. For Paoletti, this is evidence that the questions raised by the sexual revolution and the feminist movement were never resolved, ensuring that the debates around transgender identity, contraception, and gay marriage would still be active today.

Unisex fashion waned in the mid-to-late '70s. Workers struggling to land jobs in a weak economy sought a more conservative style, Paoletti argues, bringing back suits for men and inspiring Diane Von Furstenberg wrap dresses for women. Certain unisex elements lingered—pants for women, for instance. In other areas, like children's clothing, dressing became gendered to the extreme. In Paoletti's opinion, rigidly gendered clothes box us into categories that might not fit our true selves. "In an exercise in aspirational dressing, consider the possibilities if our wardrobes reflected the full range of choices available to each of us," she writes in the book’s last chapter. "Imagine that we dressed to express our inner selves and our locations not as fixed but as flexible."

What's ironic is that Paoletti herself analyzes fashion not as individual expression, but as collective political speech. At one point, she quotes journalist Clara Pierre, who commented wistfully (and prematurely) in 1976 that "clothes no longer have to perform the duty of [sexual] differentiation and can relax into just being clothes." Paoletti claims to share Pierre’s hope, yet her book never allows clothes to “relax” in such a manner. Rather, they are reflections of or rebellions against gender binaries. At times, Paoletti seems frightened of the prospect of clothes without subtext. "The fashion industry has spent billions of dollars convincing us that fashion is frivolous," she writes in the introduction. "Yes, fashion is fun, but clothing is also bound up with the most serious business we do as humans: expressing ourselves as we understand ourselves."

In reality, clothing communicates information not just about gender, but also about race, class, age, workplace, personality, sense of humor, social media habits, or musical tastes. Used in combination, its messages—serious and frivolous—lead to creative, original style. Of course, it would be impossible for a single book to consider the myriad identities expressed through dress. Paoletti acknowledges that her book bypasses, for instance, the influence of race on ‘60s and ‘70s fashion, when the Black Power movement helped popularize natural hairstyles. For reasons of clarity, she says, she limited her approach to gender—specifically, gender as expressed through middle-class, mainstream style.

Paoletti's scope, while restrictive, is also refreshing. To study fashion via the masses is rare. Much of fashion scholarship and criticism focuses on luxury designers, or else subcultural groups like punk, rave, or, most recently, normcore. Fashion isn't just a byproduct of mass social movements, as Paoletti analyzes it—but neither is it the confection of a few aesthetic geniuses, as it's often portrayed.

Of course, it's possible to dress originally and make a statement about gender. Which brings us back to Jaden Smith. In the weeks before Coachella, he posted this Instagram caption: "Went To Top Shop To Buy Some Girl Clothes, I Mean 'Clothes.'" Unisex is alive and well, it seems. If only Willow, Jada, and Will would don matching tunics and flower crowns for a family portrait, it would be an all-out revival.