How Bathing Suits Went From Two-pieces to Long Gowns and Back

Bikinis may have been illegal in 1900, but they were all the rage in ancient Rome

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20120622011547709px-Potomac_Tidal_Basin_female_swimmers-small.jpg)

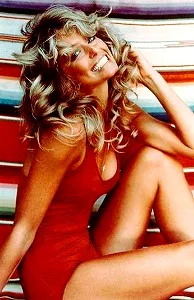

We can’t all have our beach poses topped with copious, feathered blond locks, but we do all require swimwear, especially now that summer is upon us. As the thermometer rises, we seek water: a dip in the ocean, lounging poolside, hopping through an open fireplug on the street. All of which means donning a bathing suit.

And that often means finding a bathing suit, which can be overwhelming considering the surplus of options: a one- or two-piece; sport or leisure, monotone or patterned?

It wasn’t always so. Waterborne fashion has exploded in the past 50 years, from just a small range of fabrics, styles and cuts – and that’s a dramatic step forward from the humble origins of bathing gear in previous centuries. The tailors who trimmed yards of fabric into aquatic cover-ups for 18th century women could never have imagined that what they sewed would eventually evolved in Farrah in the dramatic red, and beyond.

Here on Threaded – which, if you are new, and you probably are, since we are new, our new clothing and history blog, (Welcome!) – we’ll be looking at swimwear over the next couple months as summer gets more, well, summery. Throughout this series, we’ll be looking into the Institution’s collection, like Farrah’s bathing suit, which was recently donated to the Smithsonian – and moving beyond – to explore the cultural history, key players, and finer details of this water-bound costume.

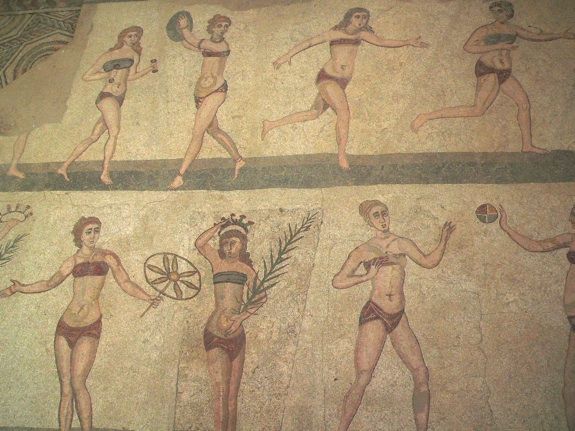

Our story begins in the 4th century when the Villa Roma de Casale in Sicily was decorated with the first known representation of women wearing bathing suits. As the Roman mosaic-makers would have it, those early Sicilian women were portrayed exercising in what appears to be bikini-like suits, bandeau top and all.

From there we must skip ahead as it appears from the artistic record that there were many centuries when no one ventured into the water—until 1687, when English traveler Celia Fiennes documents the typical lady’s bathing costume of that era:

The Ladyes go into the bath with Garments made of a fine yellow canvas, which is stiff and made large with great sleeves like a parson’s gown; the water fills it up so that it is borne off that your shape is not seen, it does not cling close as other linning, which Lookes sadly in the poorer sort that go in their own linning. The Gentlemen have drawers and wastcoates of the same sort of canvas, this is the best linning, for the bath water will Change any other yellow.

“Bathing gowns,” as they were referred to, in the late 18th century, were used for just that, public bathing, a standard mode of hygiene at the time. In fact, “bathing machines,” four-wheeled carriages that would be rolled out into the water and designed for the bather’s utmost modesty, were popular accessories to the bathing gown.

In the century that follows, modesty prevailed over form and function. Women took to the water in long dresses made from fabric that wouldn’t become transparent when submerged. To prevent the garments from floating up to expose any precious calf (or beyond, heaven forbid), some women are thought to have sewn lead weights into the hem to keep the gowns down.

In the mid-19thcentury and into the early 20th century, bathing dresses continued to cover most of the female figure. Bloomers, popularized by one Amelia Bloomer, were adapted for the water and worn with tunics, all of which were made from heavy, flannel or wool fabric that would weigh down the wearer, not quite convenient for negotiation the surf.

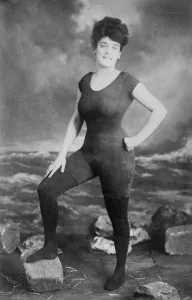

Then in 1907, a scandal erupted when Australian swimmer, Annette Kellerman, the first woman to swim across the English Channel, was arrested in Boston for wearing a more form-fitting, one-piece suit. (Turns out arrests for indecency on beaches were not uncommon during that time.) Her form-fitting suit paved the way for a new kind of one-piece, and over the next couple decades, as swimming became an even more popular leisure-time activity, beach goers saw more arms, legs, and necks than ever before.

In 1915, Jantzen, a small knittery in Portland, broke new ground by making a “swimming suit” from wool and officially coining the term six years later. Not long after, the company introduced its “Red Diving Girl” logo that was just risqué enough for the time to embody a specific point of view from the Roaring 20s.

The Red Diving Girl became an enormously popular image and turned Jantzen into a powerhouse by commercializing the burgeoning liberation of femininity at the water’s edge.

Then came the French. Jantzen’s diver was puritan in comparison to what French engineer Louis Réard first called the bikini in 1946. As the story goes, Réard chose the name because of recent atomic tests at Bikini Atoll in the Pacific Ocean. His idea was that this new suit would have the same explosive effect as splitting the atom did on its island namesake.

At first the effect was too explosive. It took some time to catch on but eventually the bikini was all over the beaches, and popular culture. By the 1960s, even Annette Funicello, onetime darling of the Mickey Mouse Club, wore a two-piece on the silver screen.

From there and up to today, swimwear has fanned out in all directions: roomier blouson bathing suits, retro, high-waisted two-pieces; Burkinis (for devout Muslim bathers); UV-protective swim shirts; and the ever-popular thong. Today’s tiniest g-string is still not quite as revealing as fashion designer Rudi Gernreich’s monokini, released in 1964, and which was essentially just the lower half of a bikini suspended with two halter straps.

How far we’ve come only makes it all the more striking that Fawcett’s poster had such an enormous cultural impact, selling 12 million copies in 1975, and making her a star. This was the height of the sexual revolution, after all, a time when – if Dazed and Confused is to be believed – teenage girls raced to reveal bikini-impact skin while sitting in English class. And yes, there was Farrah, essentially modeling what the Jantzen diver wore during Prohibition. The neck on Farrah’s red suit was a bit deeper, and there was her smile, whiter than white. Whereas Bardot’s bikini and pout made her a vivid, voluptuous sex kitten, Farrah, grinning in her red one-piece, was an All-American Girl, just having a nice time at the beach and displaying only a hint of sexuality. The French may flaunt it, but deep down, we Americans still like our sexuality suggested. And then taped to the wall.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/emily-spivack-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/emily-spivack-240.jpg)