How the Paperback Novel Changed Popular Literature

Classic writers reached the masses when Penguin paperbacks began publishing great novels for the cost of a pack of cigarettes

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Sir-Allen-Lane-Penguin-Books-631.jpg)

The story about the first Penguin paperbacks may be apocryphal, but it is a good one. In 1935, Allen Lane, chairman of the eminent British publishing house Bodley Head, spent a weekend in the country with Agatha Christie. Bodley Head, like many other publishers, was faring poorly during the Depression, and Lane was worrying about how to keep the business afloat. While he was in Exeter station waiting for his train back to London, he browsed shops looking for something good to read. He struck out. All he could find were trendy magazines and junky pulp fiction. And then he had a “Eureka!” moment: What if quality books were available at places like train stations and sold for reasonable prices—the price of a pack of cigarettes, say?

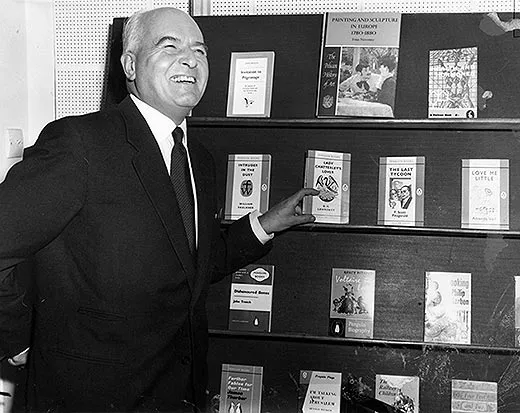

Lane went back to Bodley Head and proposed a new imprint to do just that. Bodley Head did not want to finance his endeavor, so Lane used his own capital. He called his new house Penguin, apparently upon the suggestion of a secretary, and sent a young colleague to the zoo to sketch the bird. He then acquired the rights to ten reprints of serious literary titles and went knocking on non-bookstore doors. When Woolworth’s placed an order for 63,500 copies, Lane realized he had a viable financial model.

Lane’s paperbacks were cheap. They cost two and a half pence, the same as ten cigarettes, the publisher touted. Volume was key to profitability; Penguin had to sell 17,000 copies of each book to break even.

The first ten Penguin titles, including The Mysterious Affair at Styles by Agatha Christie, A Farewell to Arms by Ernest Hemingway and The Unpleasantness at the Bellona Club by Dorothy Sayers, were wildly successful, and after just one year in existence, Penguin had sold over three million copies.

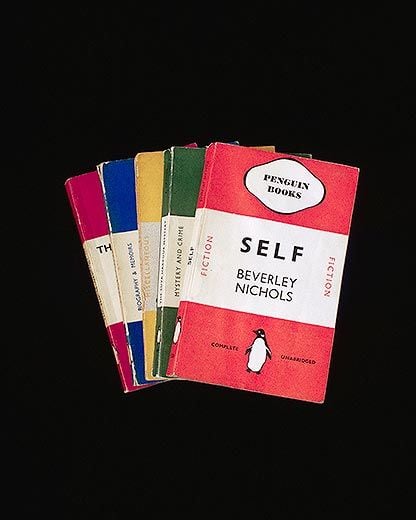

Penguin’s graphic design played a large part in the company’s success. Unlike other publishers, whose covers emphasized the title and author of the book, Penguin emphasized the brand. The covers contained simple, clean fonts, color-coding (orange for fiction, dark blue for biography) and that cute, recognizable bird. The look helped gain headlines. The Sunday Referee declared “the production is magnificent” and novelist J. B. Priestley raved about the “perfect marvels of beauty and cheapness.” Other publishing houses followed Penguin’s lead; one, Hutchinson, launched a line called Toucan Books.

With its quality fare and fine design, Penguin revolutionized paperback publishing, but these were not the first soft-cover books. The Venetian printer and publisher Aldus Manutius had tried unsuccessfully to publish some in the 16th century, and dime novels, or “penny dreadfuls” –lurid romances published in double columns and considered trashy by the respectable houses, were sold in Britain before the Penguins. Until Penguin, quality books, and books whose ink did not stain one's hands, were available only in hardcover.

In 1937, Penguin expanded, adding a nonfiction imprint called Pelican, and publishing original titles. Pelican’s first original nonfiction title was George Bernard Shaw’s The Intelligent Woman’s Guide to Socialism, Capitalism, Sovietism & Fascism. It also published left-leaning Penguin Specials such as Why Britain Is at War and What Hitler Wants that sold widely. As these titles reveal, Penguin played a role in politics as well as in literature and design, and its left-leaning stance figured into Britain’s war and postwar efforts. After the Labour Party came to office in 1945, one of the party leaders declared that the accessibility of left-leaning reading during the war helped his party succeed: “After the WEA [Workers’ Educational Association] it was Lane and his Penguins which did most to get us into office at the end of the war.” The ousted Conservative Party opened an exhibition on the unfortunate spread of Socialism and included photographs of those responsible, including one of Lane.

During World War II, Penguins, which were small enough to be stowed in the pocket of a uniform, were carried by soldiers, and they were chosen for the Services Central and the Forces Book Clubs. In 1940, Lane launched an imprint for youngsters, Puffin Picture Books, which children facing evacuation could carry with them to their new, uncertain homes. During the times of paper rationing, Penguin fared better than its competitors, and the books’ simple design allowed Penguin to easily accommodate the typographic restrictions. Author and professor Richard Hoggart, who served in the war, noted that the books “became a signal: if the back trouser pocket bulged in that way that usually indicated a reader.” They were also carried in the bag in which gas masks were carried and above the left knee of battle dress.

The United States adopted the Penguin model in 1938 with the creation of Pocket Books. The first Pocket Book title was The Good Earth by Pearl Buck, and it was sold in Macy’s. Unlike Penguin, Pocket Books were lavishly illustrated with bright covers. Other U.S. paperback companies followed Pocket’s lead, and like Penguin, the books were carried by soldiers. One soldier, who had been shot and was waiting in a foxhole for help, “spent the hours before help came reading Willa Cather’s Death Comes for the Archbishop, the Saturday Evening Post reported in 1945. “He grabbed it the day before under the delusion that it was a murder mystery, but he discovered, to his amazement, that he liked it anyway.” Avon, Dell, Ace and Harlequin published genre fiction and new literary titles, including novels by Henry Miller and John Steinbeck.

Allen Lane stated that he “believed in the existence…of a vast reading public for intelligent books at a low price, and staked everything on it.” Seventy-five years later, we find ourselves in a situation not unlike Lane’s in 1935. Publishers are facing plummeting sales, and many are attempting to launch new models, chasing the dream to be the next Penguin. New e-readers have been unveiled recently, including the iPad, Kindle and Nook. Digital editions are cheaper than paperbacks—you can buy the latest literary fiction for $9.99—but they come with a hefty start-up price. The basic iPad costs $499, and the two versions of the Kindle are priced at $259 and $489. Not exactly the price of a pack of cigarettes—or, to use a healthier analogy, a pack of gum.

Correction: The original version of this story incorrectly stated the cost of Penguin paperbacks. It was two and a half pence, not six pence.