How Thomas Jefferson Created His Own Bible

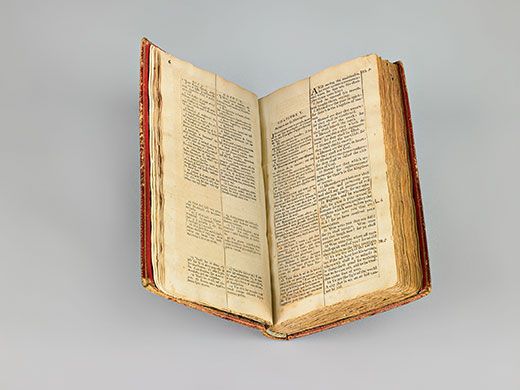

Thanks to an extensive restoration process, the public can now see how Jefferson created his own version of the Scripture

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/atm-object-at-hand-Thomas-Jefferson-bible-631.jpg)

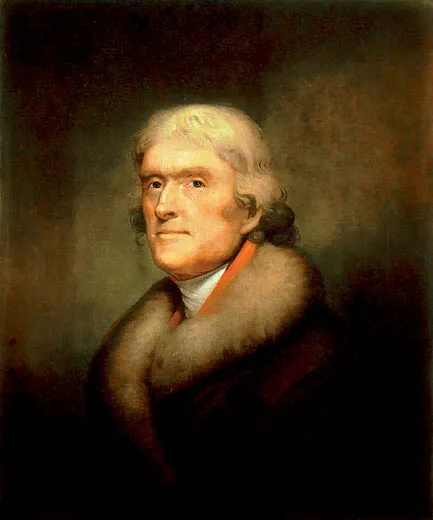

Thomas Jefferson, together with several of his fellow founding fathers, was influenced by the principles of deism, a construct that envisioned a supreme being as a sort of watchmaker who had created the world but no longer intervened directly in daily life. A product of the Age of Enlightenment, Jefferson was keenly interested in science and the perplexing theological questions it raised. Although the author of the Declaration of Independence was one of the great champions of religious freedom, his belief system was sufficiently out of the mainstream that opponents in the 1800 presidential election labeled him a “howling Atheist.”

In fact, Jefferson was devoted to the teachings of Jesus Christ. But he didn’t always agree with how they were interpreted by biblical sources, including the writers of the four Gospels, whom he considered to be untrustworthy correspondents. So Jefferson created his own gospel by taking a sharp instrument, perhaps a penknife, to existing copies of the New Testament and pasting up his own account of Christ’s philosophy, distinguishing it from what he called “the corruption of schismatizing followers.”

The second of the two biblical texts he produced is on display through May 28 at the Albert H. Small Documents Gallery of the Smithsonian National Museum of American History (NMAH) after a year of extensive repair and conservation. “Other aspects of his life and work have taken precedence,” says Harry Rubenstein, chair and curator of the NMAH political history division. “But once you know the story behind the book, it’s very Jeffersonian.”

Jefferson produced the 84-page volume in 1820—six years before he died at age 83—bound it in red leather and titled it The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth. He had pored over six copies of the New Testament, in Greek, Latin, French and King James English. “He had a classic education at [the College of] William & Mary,” Rubenstein says, “so he could compare the different translations. He cut out passages with some sort of very sharp blade and, using blank paper, glued down lines from each of the Gospels in four columns, Greek and Latin on one side of the pages, and French and English on the other.”

Much of the material Jefferson elected to not include related miraculous events, such as the feeding of the multitudes with only two fish and five loaves of barley bread; he eschewed anything that he perceived as “contrary to reason.” His idiosyncratic gospel concludes with Christ’s entombment but omits his resurrection. He kept Jesus’ own teachings, such as the Beatitude, “Blessed are the peace-makers: for they shall be called the children of God.” The Jefferson Bible, as it’s known, is “scripture by subtraction,” writes Stephen Prothero, a professor of religion at Boston University.

The first time Jefferson undertook to create his own version of Scripture had been in 1804. His intention, he wrote, was “the result of a life of enquiry and reflection, and very different from that anti-Christian system, imputed to me by those who know nothing of my opinions.” Correspondence indicates that he assembled 46 pages of New Testament passages in The Philosophy of Jesus of Nazareth. That volume has been lost. It focused on Christ’s moral teachings, organized by topic. The 1820 volume contains not only the teachings, but also events from the life of Jesus.

The Smithsonian acquired the surviving custom bible in 1895, when the Institution’s chief librarian, Cyrus Adler, purchased it from Jefferson’s great-granddaughter, Carolina Randolph. Originally, Jefferson had bequeathed the book to his daughter Martha.

The acquisition revealed the existence of the Jefferson Bible to the public. In 1904, by act of Congress, his version of Scripture, regarded by many as a newly discovered national treasure, was printed. Until the 1950s, when the supply of 9,000 copies ran out, each newly elected senator received a facsimile Jefferson Bible on the day that legislator took the oath of office. (Disclosure: Smithsonian Books has recently published a new facsimile edition.)

The original book now on view has undergone a painstaking restoration led by Janice Stagnitto Ellis, senior paper conservator at the NMAH. “We re-sewed the binding,” she says, “in such a way that both the original cover and the original pages will be preserved indefinitely. In our work, we were Jefferson-level meticulous.”

“The conservation process,” says Harry Rubenstein, “has allowed us to exhibit the book just as it was when Jefferson last handled it. And since digital pictures were taken of each page, visitors to the exhibition—and visitors to the web version all over the world—will be able to page through and read Jefferson’s Bible just as he did.”

Owen Edwards is a freelance writer and author of the book Elegant Solutions.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)