How to Crochet a Coral Reef

A ball of yarn—and the work of more than 800 people—could go a long way toward saving endangered sea life

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Coral-Reef-crochet-631.jpg)

The Natural History Museum's Baird Auditorium showcases scientists and performers from around the world. One day it might be a lecture on evolution, the next a Puerto Rican dance recital. On this particular rainy fall afternoon, however, the auditorium is quiet—though not for lack of activity. More than 100 women, from young girls to grandmothers, are deftly manipulating crochet hooks, winding together brightly colored yarn, lanyard string, old curtain tassels, plastic bags and even unwound audiocassette tape.

As the forms begin to take shape, they reveal frilly, crenulated structures that will be displayed alongside the "Hyperbolic Crochet Coral Reef" exhibit, now on view in Natural History's Sant Ocean Hall.

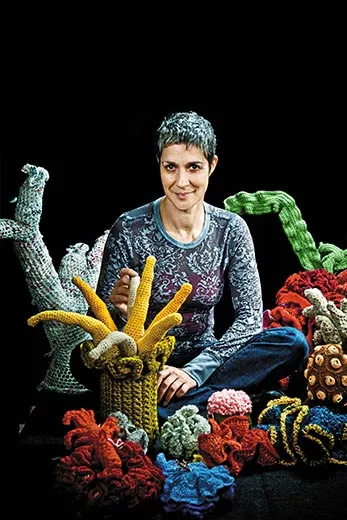

"We started off with something very simple, and then we started deviating, morphing the code," says exhibit director Margaret Wertheim, 52, about the coral reef, as she watches the crocheters from the stage.

Wertheim, an Australian-born science journalist, first began crocheting with her artist sister Christine in 2003 to try her hand at modeling hyperbolic space—the mind-bending geometry discovered by mathematicians in the early 19th century. Whereas conventional geometry describes shapes on a flat plane, hyperbolic geometry is set on a curved surface—creating configurations that defy the mathematical theorems discovered by Euclid some 2,000 years ago. Variations of hyperbolic space can be found in nature (the wavy edges of sea kelp, for example), but mathematicians scratched their heads trying to find a simple way to fabricate a physical model. Finally, in 1997, mathematician Daina Taimina realized that the crochet stitch that women have used for centuries to create ruffled garments represents this complex geometry.

Having grown up in Queensland, where the Great Barrier Reef lies offshore, the Wertheim sisters were astonished to learn that their crocheted models looked a lot like another example of hyperbolic geometry in nature. "We had them sitting on our coffee table," says Wertheim, "and we looked at them and said, 'Oh my gosh, they look like a coral reef. We could crochet a coral reef.'"

The exhibit first appeared at Pittsburgh's Andy Warhol Museum in 2007. And wherever it goes, Wertheim encourages the local community to create its own reef. Among the contributors are churches, synagogues, schools, retirement homes, charities and even government agencies.

Curators and scientists attribute the reef's popularity to its unique combination of marine biology, exotic math, traditional handicraft, conservation and community. "All these different elements are bubbling on the stove together," says Smithsonian biologist Nancy Knowlton. "For different people, there are different parts of it that really resonate."

Like the Wertheims' exhibit, the contribution from Washington, D.C. residents is divided into sections. A vibrant "healthy" reef is organized roughly by color and species (a green crocheted kelp garden, for example); a "bleached reef" is made up of pale, neutral colors—which represent coral subjected to pollution and rising water temperatures, provoking a stress response that drains the coral's bright hues. In addition to yarn, the crocheters use recycled materials (such as the cassette tapes and plastic bags) to call attention to the excessive human waste that accumulates in the ocean.

Wertheim says it would be hubristic to claim that her project alone could make people care about endangered reefs. Yet the last three years have brightened her outlook.

"A reef is made up of billions of coral polyps," she says. "Each one of these is completely insignificant individually, but collectively, they make up something as magnificent as the Great Barrier Reef. We humans, when we work together, can do amazing things."

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/jess-righthand-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/jess-righthand-240.jpg)