Inside America’s Great Romance With Norman Rockwell

A new biography of the artist reveals the complex inner life of our greatest and most controversial illustrator

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/norman-rockwell-631.jpg)

I did not grow up with a Norman Rockwell poster hanging in my bedroom. I grew up gazing at a Helen Frankenthaler poster, with bright, runny rivulets of orange and yellow bordering a rectangle whose center remained daringly blank. As an art history major, and later as an art critic, I was among a generation that was taught to think of modern art as a kind of luminous, cleanly swept room. Abstract painting, our professors said, jettisoned the accumulated clutter of 500 years of subject matter in an attempt to reduce art to pure form.

Rockwell? Oh God. He was viewed as a cornball and a square, a convenient symbol of the bourgeois values Modernism sought to topple. His long career overlapped with the key art movements of the 20th century, from Cubism to Minimalism, but while most avant-gardists were heading down a one-way street toward formal reduction, Rockwell was driving in the opposite direction—he was putting stuff into art. His paintings have human figures and storytelling, snoozing mutts, grandmothers, clear-skinned Boy Scouts and wood-paneled station wagons. They have policemen, attics and floral wallpaper. Moreover, most of them began life as covers for the Saturday Evening Post, a weekly general-interest magazine that paid Rockwell for his work, and paychecks, frankly, were another Modernist no-no. Real artists were supposed to live hand-to-mouth, preferably in walk-up apartments in Greenwich Village.

The scathing condescension directed at Rockwell during his lifetime eventually made him a prime candidate for revisionist therapy, which is to say, an art-world hug. He received one posthumously, in the fall of 2001, when Robert Rosenblum, the brilliant Picasso scholar and art-world contrarian in chief, presided over a Rockwell exhibition at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York. It represented a historic collision between mass taste and museum taste, filling the pristine spiral of the Gugg with Rockwell’s plebeian characters, the barefoot country boys and skinny geezers with sunken cheeks and Rosie the Riveter sitting triumphantly on a crate, savoring her white-bread sandwich.

The great subject of his work was American life—not the frontier version, with its questing for freedom and romance, but a homelier version steeped in the we-the-people, communitarian ideals of America’s founding in the 18th century. The people in his paintings are related less by blood than by their participation in civic rituals, from voting on Election Day to sipping a soda at a drugstore counter.

Because America was a nation of immigrants who lacked universally shared traditions, it had to invent some. So it came up with Thanksgiving, baseball—and Norman Rockwell.

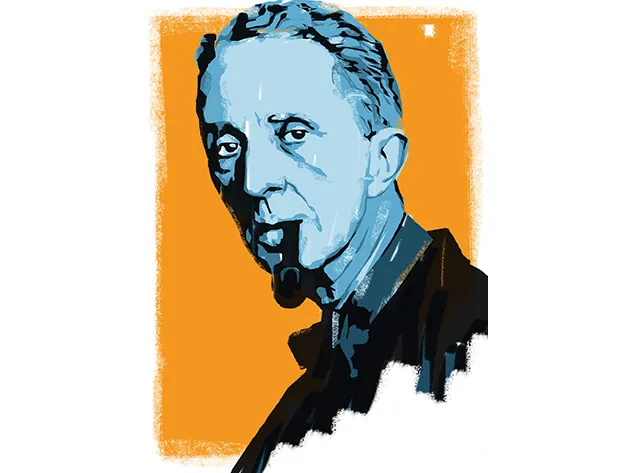

Who was Rockwell? A lean, bluish man with a Dunhill pipe, his features arranged into a gentle mask of neighborliness. But behind the mask lay anxiety and fear of his anxiety. On most days, he felt lonesome and loveless. His relationships with his parents, wives and three sons were uneasy, sometimes to the point of estrangement. He eschewed organized activity. He declined to go to church.

Although Rockwell is often described as a portrayer of the nuclear family, this is a misconception. Of his 322 covers for the Saturday Evening Post, only three portray a conventional family of parents and two or more children (Going and Coming, 1947; Walking to Church, 1953; and Easter Morning, 1959). Rockwell culled the majority of his figures from an imaginary assembly of boys and fathers and grandfathers who convene in places where women seldom intrude. Boyishness is presented in his work as a desirable quality, even in girls. Rockwell’s female figures tend to break from traditional gender roles and assume masculine guises. Typically, a redheaded girl with a black eye sits in the hall outside the principal’s office, grinning despite the reprimand awaiting her.

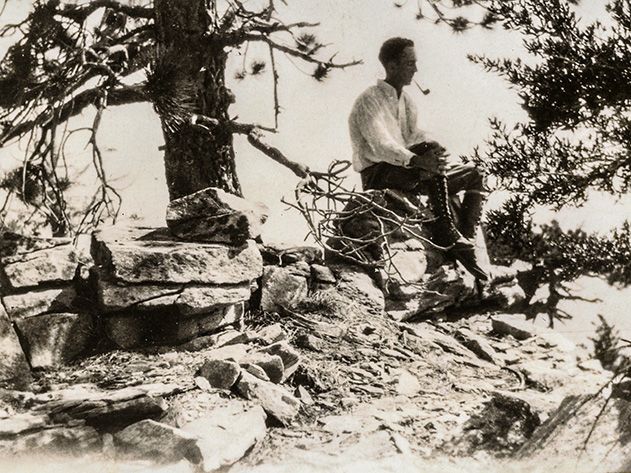

Although he married three times and raised a family, Rockwell acknowledged that he didn’t pine for women. They made him feel imperiled. He preferred the nearly constant companionship of men whom he perceived as physically strong. He sought out friends who went fishing in the wilderness and trekked up mountains, men with mud on their shoes, daredevils who were not prim and careful the way he was. “It may have represented Rockwell’s solution to the problem of feeling wimpish and small,” maintains Sue Erikson Bloland, a psychotherapist and the daughter of pioneering psychoanalyst Erik Erikson, whom Rockwell consulted in the 1950s. “He had a desire to connect with other men and partake of their masculinity, because of a sense of deficiency in himself.”

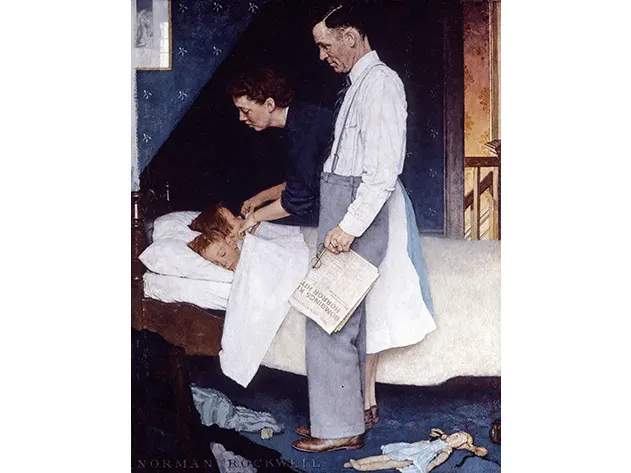

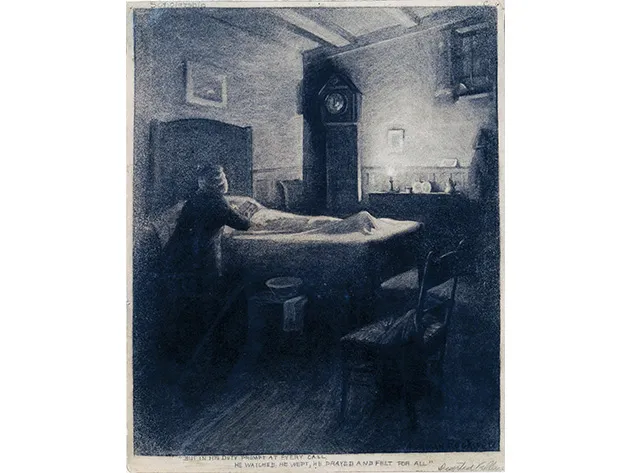

Revealingly, his earliest known work portrays an elderly man ministering to a bedridden boy. The charcoal drawing has never been reproduced until now. Rockwell was 17 years old when he made it, and for years it languished in storage at the Art Students League, which had purchased it from the artist when he was a student there. Consequently, the drawing was spared the fate of innumerable early Rockwells that were lost over the years or destroyed in a disastrous fire that consumed one of his barn-studios in later life.

Not long ago, I contacted the League to ask if it still owned the drawing and how I could see it; it was arranged that the work would be driven into Manhattan from a New Jersey warehouse. It was incredible to see—a marvel of precocious draftsmanship and a shockingly macabre work for an artist known for his folksy humor. Rockwell undertook it as a class assignment. Technically, it’s an illustration of a scene from “The Deserted Village,” the 18th-century pastoral poem by Oliver Goldsmith. It takes you into a small, tenebrous, candlelit room where a sick boy lies supine in bed, a sheet pulled up to his chin. A village preacher, shown from the back in his long coat and white wig, kneels at the boy’s side. A grandfather clock looms dramatically in the center of the composition, infusing the scene with a time-is-ticking ominousness. Perhaps taking his cue from Rembrandt, Rockwell is able to extract great pictorial drama from the play of candlelight on the back wall of the room, a glimpse of radiance in the unreachable distance.

Rockwell had been taught in Thomas Fogarty’s illustration class that pictures are “the servant of text.” But here he breaks that rule. Traditionally, illustrations for “The Deserted Village” have emphasized the theme of exodus, portraying men and women driven out of an idyllic, tree-laden English landscape. But Rockwell moved his scene indoors and chose to capture a moment of tenderness between an older man and a young man, even though no such scene is described in the poem.

Put another way, Rockwell was able to do the double duty of fulfilling the requirements of illustration while staying true to his emotional instincts. The thrill of his work is that he was able to use a commercial form to work out his private obsessions.

***

Rockwell, who was born in New York City in 1894, the son of a textile salesman, attributed much about his life and his work to his underwhelming physique. As a child he felt overshadowed by his older brother, Jarvis, a first-rate student and athlete. Norman, by contrast, was slight and pigeon-toed and squinted at the world through owlish glasses. His grades were barely passing and he struggled with reading and writing—today, he surely would be labeled dyslexic. Growing up in an era when boys were still judged largely by their body type and athletic prowess, he felt, he once wrote, like “a lump, a long skinny nothing, a bean pole without beans.”

It did not help that he grew up at a time when the male body—as much as the mind—had come to be viewed as something to be improved and expanded. President Theodore Roosevelt himself was an advocate of body modification. Much of Rockwell’s childhood (ages 7 to 15) took place during the daunting athleticism of Teddy Roosevelt’s presidency. He was the president who had transformed his sickly, asthmatic body into a muscular one, the naturalist president who hiked for miles and hunted big game. In the T.R. era, the well-developed male body became a kind of physical analogue to America’s expansionist, big-stick foreign policy. To be a good American was to build your deltoids and acquire a powerful chest.

Rockwell tried exercising, hoping for a transformation. In the mornings, he diligently did push-ups. But the body he espied in the mirror—the pale face, the narrow shoulders and spaghetti arms—continued to strike him as wholly unappealing.

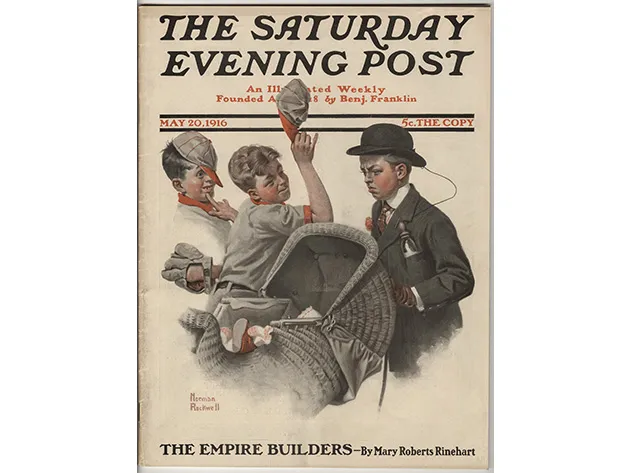

In 1914, Rockwell and his parents settled in a boardinghouse in New Rochelle, New York, which was then a veritable art colony. The Golden Age of Illustration was at its peak and New Rochelle’s elite included J.C. Leyendecker, the star cover artist for the Saturday Evening Post. There was more new art by American artists to be found in magazines than there was on the walls of museums.

Rockwell wanted mainly one thing. He wanted to get into the Saturday Evening Post, a Philadelphia-based weekly and the largest-circulation magazine in the country. It didn’t come out on Saturdays, but on Thursdays. No one waited until the weekend to open it. Husbands and wives and precocious children vied to get hold of the latest issue in much the same way that future generations would vie over access to the household telephone or the remote control.

Rockwell’s first cover for the Post, for which he was paid a whopping $75, appeared in the May 20, 1916, issue. It remains one of his most psychologically intense works. A boy who appears to be about 13 is taking his infant sister out for some fresh air when he bumps into two friends. The boy is mortified to be witnessed pushing a baby carriage. While his friends are clad in baseball uniforms and heading off to a game, the baby-sitting boy is dressed formally, complete with a starched collar, bowler hat and leather gloves. His eyes are averted and almost downcast as he hurries along, as if it were possible to physically escape the mocking gaze of his tormentors.

Rockwell became an immediate sensation, and his work began appearing on the cover of the Saturday Evening Post about once a month, as often as his hero and neighbor J.C. Leyendecker. The two illustrators eventually became close friends. Rockwell spent many pleasant evenings at Leyendecker’s hilltop mansion, an eccentric household that included Leyendecker’s illustrator-brother, Frank; his sister, Augusta; and J.C.’s male lover, Charles Beach. Journalists who interviewed Rockwell at his studio in New Rochelle were charmed by his boyish appearance and abundant modesty. He would invariably respond to compliments by knocking on wood and claiming that his career was about to collapse. Asked about his artistic gifts, he brushed them off, explaining, “I agree with Thomas Edison when he says that genius is 1 percent inspiration and 99 percent perspiration.”

By the time his first Post cover had appeared, Rockwell had impulsively proposed marriage to Irene O’Connor, an Irish-Catholic schoolteacher whom he met at the boardinghouse in New Rochelle. “After we’d been married awhile I realized that she didn’t love me,” Rockwell later wrote. He never seemed to flip the question and contemplate whether or not he loved her. The marriage, which produced no children, somehow lasted nearly 14 years. Irene filed for divorce in Reno, Nevada, a few months after the Great Crash.

Rockwell wasted no time in picking a second wife. He was visiting Los Angeles when he met 22-year-old Mary Barstow at the home of dear friend Clyde Forsythe, a cartoonist and landscape painter. Mary, who smoked Lucky Strikes and had frizzy hair, had graduated from Stanford the previous spring in the class of 1929. He had known her for exactly two weeks when he asked her to marry him. On March 19, 1930, they applied for a marriage license at the Los Angeles County Courthouse. He gave his age as 33, chopping off three years, perhaps because he could not imagine why a fetching woman like Mary Barstow would want to marry an aging, panic-stricken divorcé.

For the next decade, he and Mary lived in a handsome white Colonial in New Rochelle, a suburb in which a certain kind of life is supposed to unfold. But within the first year of their marriage, she began to feel excluded from her husband’s company. He derived something intangible from his assistant Fred Hildebrandt that she could not provide. Fred, a young artist in New Rochelle who earned his living modeling for illustrators, was attractive in a dramatic way, tall and slim, his luxuriant blond hair combed straight back. In 1930, Rockwell hired Hildebrandt to run his studio, which required that he help with tasks from building stretchers to answering the phone to sitting on a hardwood chair for hours, holding a pose.

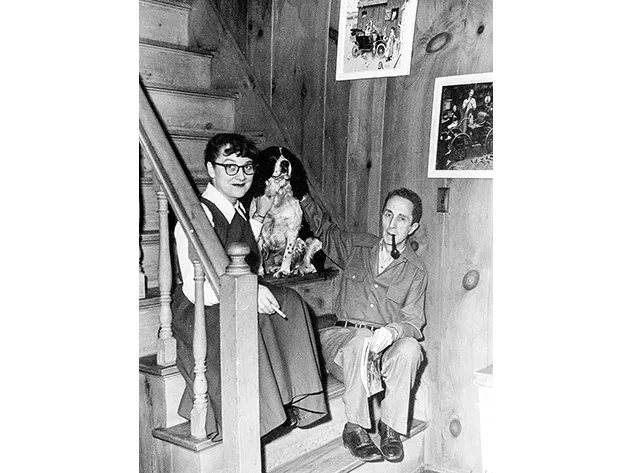

By 1933, Rockwell had become the father of two sons, Jarvis, a future artist, and Thomas, a future writer. (The youngest, Peter, a future sculptor, would arrive in 1936.) But Rockwell was grappling with the suspicion that he did not feel any more attracted to his second wife than he had to his first. He still cultivated close relationships with men outside his family. In September 1934, he and Fred Hildebrandt headed off on a two-week fishing expedition in the wilds of Canada. Rockwell kept a diary on the trip, and it records in detail the affection he felt for his friend. On September 6, Rockwell was delighted to wake up in the cold air and spot him lounging around in a new outfit. “Fred is most fetching in his long flannels,” he notes appreciatively.

That night, he and Fred played gin rummy until 11, sitting by the stove in the cabin and using a deck of cards that Rockwell had made himself. “Then Fred and I get into one very narrow bed,” he noted, referring to a rustic cot made from a hard board and a sprinkling of fir branches. The guides climbed into a bed above them, and “all during the night pine needles spray us as they drop from the guides’ bed.”

Was Rockwell gay, whether closeted or otherwise? In researching and writing this biography over the past decade, I found myself asking the question repeatedly.

Granted, he married three times, but his marriages were largely unsatisfactory. The great romance for Rockwell, to my mind, lay in his friendships with men, from whom he received something that was probably deeper than sex.

In the fall of 1938, Rockwell and Mary bought a farmhouse set on 60 acres in southern Vermont. Rockwell learned about the village of Arlington from Hildebrandt, who fished there every spring. Eager to reinvent his art by finding new models and subjects, he left New Rochelle and became a proud New Englander. However, unlike the archetypical Vermonters whom he would portray in his paintings—people who savor long afternoons on front porches—Rockwell didn’t have ten seconds to spare. A nervous man, he drank Coca-Cola for breakfast, was afflicted with backaches and coughs, and declined to swim in the Battenkill River flowing through his front yard, insisting that the water was too cold.

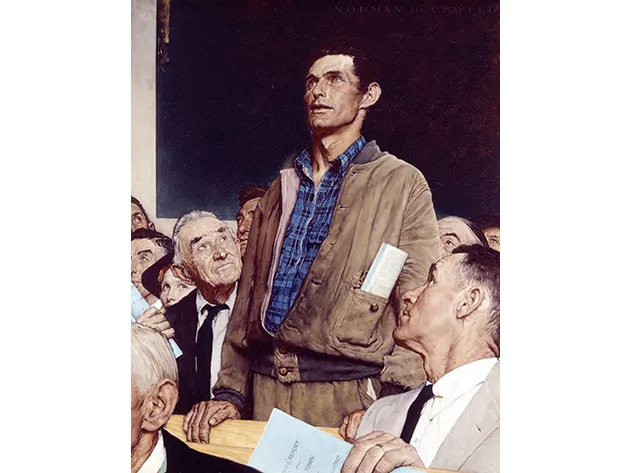

Nonetheless, the change of scenery served him well. It was in Vermont that Rockwell began using his neighbors as models and telling stories about everyday life that visualized something essential about the country. New England was, of course, the site of the American Revolution, and it was here, during World War II, that Rockwell would articulate the country’s democratic ideals anew, especially in the series of paintings that took their theme from President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Four Freedoms. Rockwell originally offered to do the paintings as war posters for the U.S. government’s Office of War Information. But on a summer afternoon in 1942 when he headed down to Arlington, Virginia, and met with OWI officials, he received a painful snub. An official declined to take a look at the studies he had brought with him, saying the government planned to use “fine arts men, real artists.”

Indeed, in coming months, Archibald MacLeish, the poet and assistant director of the agency, instead reached out to modern artists who he believed could lend some artistic prestige to the war effort. They included Stuart Davis, Reginald Marsh, Marc Chagall and even Yasuo Kuniyoshi, who, as a native of Japan, might then have seemed an unlikely choice for American war posters. Rockwell, in the meantime, spent the next seven months in a state of jittery exhaustion as he proceeded to create his Four Freedoms—not for the government, but for the Saturday Evening Post.

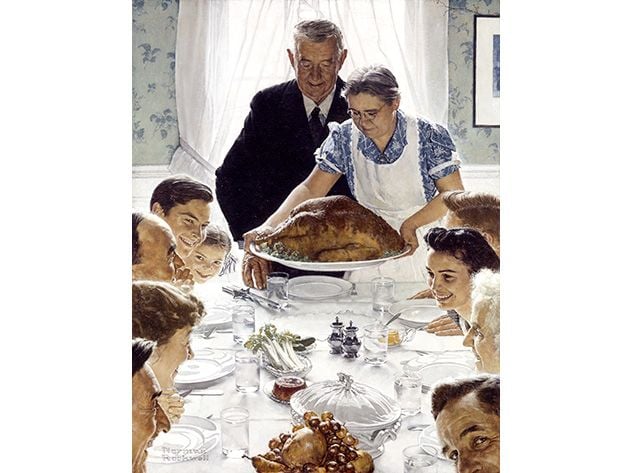

The best painting in the series is probably Freedom from Want. It takes you into the dining room of a comfortable American home on Thanksgiving Day. The guests are seated at a long table, and no one is glancing at the massive roasted turkey or the gray-haired grandma solemnly carrying it—do they even know she is there? Note the man in the lower right corner, whose wry face is pressed up against the picture plane. He has the air of a larksome uncle who perhaps is visiting from New York and doesn’t entirely buy into the rituals of Thanksgiving. He seems to be saying, “Isn’t this all just a bit much?” In contrast to traditional depictions of Thanksgiving dinner, which show the pre-meal as a moment of grace—heads lowered, praying hands raised to lips—Rockwell paints a Thanksgiving table at which no one is giving thanks. This, then, is the subject of his painting: not just the sanctity of American traditions, but the casualness with which Americans treat them.

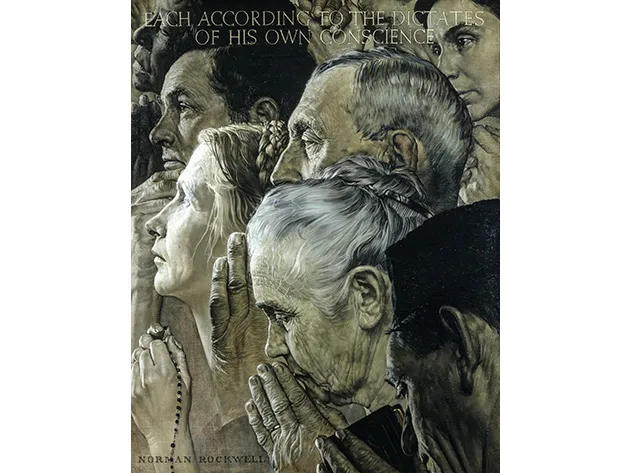

The Four Freedoms—Freedom from Want, along with Freedom of Speech, Freedom to Worship and Freedom from Fear—were published in four consecutive issues of the Post, starting on February 20, 1943, and they were instantly beloved. The Office of War Information quickly realized it had made an embarrassing mistake by rejecting them. It managed to fix the error: The OWI now arranged to print some 2.5 million Four Freedom posters and make the four original paintings the stellar centerpiece of a traveling war-bond sales campaign.

Rockwell’s Four Freedoms did not attempt to explain the war—the battles or the bloodshed, the dead and injured, the obliteration of towns. But the war wasn’t just about killing the enemy. It was also about saving a way of life. The paintings tapped into a world that seemed recognizable and real. Most everyone knew what it was like to attend a town meeting or say a prayer, to observe Thanksgiving or look in on sleeping children.

***

As Rockwell’s career flourished, Mary suffered the neglect that has befallen so many wives of artists, and she turned to alcohol for solace. Thinking he needed to be away from her, Rockwell headed to Southern California by himself in the fall of 1948. He spent a few months living out of a suitcase at the Roosevelt Hotel in Hollywood as his wife lingered in snowbound Vermont, lighting cigarettes and stubbing them out in heavy ashtrays. That was the year that Christmas Homecoming, the defining image of toasty holiday togetherness, graced the cover of the Post. It is the only painting in which all five members of the Rockwell family appear. A Christmas-day gathering is interrupted by the arrival of a son (Jarvis), whose back is turned toward the viewer. He receives a joyous hug from his mother (Mary Rockwell) as a roomful of relatives and friends look on with visible delight. In reality, there was no family gathering for the Rockwells that Christmas, only distance and discontent.

In 1951, Mary Rockwell turned for help to the Austen Riggs Center, a small psychiatric hospital in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, that catered to patients who could afford months and even years of care. She was treated by Dr. Robert Knight, the center’s medical director. In coming months, while Mary was an inpatient at Riggs, Rockwell spoke regularly with Dr. Knight to discuss her progress. Through his conversations with the doctor, he became aware of mood-lifting drugs and ways to tackle his own depression. He started taking Dexamyl, a small green pill of the combination sort, half dexedrine, half barbiturate, wholly addictive.

So too, he became interested in entering therapy himself. Dr. Knight referred him to an analyst on his staff: Erik Erikson, a German émigré who had been an artist in his wandering youth and was one of the most highly regarded psychoanalysts in the country. Rockwell’s bookkeeper remembers an afternoon when the artist casually mentioned that he was thinking of relocating to Stockbridge for the winter. By Monday, Rockwell had moved, and in fact would never return to Arlington, except to sell his house a year later.

Settling in Stockbridge, in October 1953, Rockwell acquired a studio right on Main Street, one flight above a meat market. The Austen Riggs Center was practically across the street, and Rockwell went there twice a week to meet with Erikson. Much of what Erikson did in the therapeutic hour resembled counseling, as opposed to analysis. For Rockwell, the immediate crisis was his marriage. He bemoaned his shared life with an alcoholic whose drinking, he said, made her petulant and critical of his work. Rockwell was a dependent man who tended to lean on men, and in Erikson he found reliable support. “All that I am, all that I hope to be, I owe to Mr. Erikson,” he once wrote.

Rockwell was still prone to extreme nervousness and even panic attacks. In May 1955, invited to dine at the White House, at the invitation of President Eisenhower, he flew down to Washington with a Dexamyl in his jacket pocket. He was worried he’d be tongue-tied at the “stag party,” whose guests, including Leonard Firestone of rubber-tire fame and Doubleday editor in chief Ken McCormick, were the sort of self-made, influential businessmen whose conversation Eisenhower preferred to that of politicians. The story Rockwell told about that evening goes as follows: Before dinner, standing in the bathroom of his room at the Statler Hotel, he accidentally dropped his Dexamyl pill in the sink. To his dismay, it rolled down the sink, forcing him to face the president and sup on oxtail soup, roast beef and lime sherbet ring in an anxiously unmedicated state.

By now he had been an illustrator for four decades, and he continued to favor scenes culled from everyday life. In Stockbridge, he found his younger models at the school near his house. Escorted by the principal, he would peer into classrooms, in search of boys with the right allotment of freckles, the right expression of openness. “He would come during our lunch hour and pull you into the hall,” recalled Eddie Locke, who first modeled for Rockwell as an 8-year-old. Locke is among the few who can claim the distinction of “posing somewhat in the nude,” as the Saturday Evening Post reported in a bizarrely sanguine item on March 15, 1958.

The comment refers to Before the Shot, which takes us into a doctor’s office as a boy stands on a wooden chair, his belt unfastened, his corduroy trousers lowered to reveal his pale backside. As he worriedly awaits an injection, he bends over, ostensibly to scrutinize the framed diploma hanging on the wall and reassure himself that the doctor is sufficiently qualified to perform this delicate procedure. (That’s the joke.)

Before the Shot remains the only Rockwell cover in which a boy exposes his unclad rear. Locke recalls posing for the picture in a doctor’s office on an afternoon when the doctor was gone. Rockwell asked the boy to drop his pants and had his photographer take the pictures. “He instructed me to pose how he wanted it,” Locke recalled. “It was a little uncomfortable, but you just did it, that’s all.”

One night, Rockwell surprised the boy’s family by stopping by their house unannounced. He was carrying the finished painting and apparently needed to do a bit more research. “He asked for the pants,” Locke recalled years later. “This is what my parents told me. He asked for the pants to see if he had gotten the color right. They’re kind of a grey-green.” It’s an anecdote that reminds you of both his fastidious realism and the sensuality he attached to fabric and clothing.

***

In August 1959, Mary Rockwell died suddenly, never waking up from an afternoon nap. Her death certificate lists the cause as “coronary heart disease.” Her friends and acquaintances wondered whether Mary, who was 51, had taken her own life. At Rockwell’s request, no autopsy was performed; the quantity of drugs in her bloodstream remains unknown. Rockwell spoke little about his wife in the weeks and months following her death. After three turbulent decades of marriage, Mary had been eradicated from his life without warning. “He didn’t talk about his feelings,” recalled his son Peter. “He did some of his best work during that period. He did some fabulous paintings. I think we were all relieved by her death.”

The summer of 1960 arrived, and Senator John F. Kennedy was anointed by the Democratic National Convention as its candidate. Rockwell had already begun his portrait of him and visited the Kennedy compound in Hyannis Port. At the time, Kennedy’s advisers were concerned that the 43-year-old candidate was too young to seek the office of the presidency. He implored Rockwell, in his portrait for the cover of the Post, to make him look “at least” his age. Rockwell was charmed by the senator, believing there was already a golden aura about him.

Rockwell had also met with the Republican nominee, Vice President Richard Nixon. As much as he admired President Eisenhower, Rockwell did not care for his vice president. In his studio, he worked on the portraits of Senator Kennedy and Vice President Nixon side by side. Scrupulously objective, he made sure that neither candidate flashed a millimeter more of a smile than the other. It was tedious work, not least because Nixon’s face posed unique challenges. As Peter Rockwell recalled, “My father said the problem with doing Nixon is that if you make him look nice, he doesn’t look like Nixon anymore.”

In January 1961, Kennedy was inaugurated, and Rockwell, a widower living in a drafty house with his dog Pitter, listened to the ceremony on his radio. For several months, Erik Erikson had been exhorting him to join a group and get out of the house. Rockwell signed up for “Discovering Modern Poetry,” which met weekly at the Lenox Library. The spring term started that March. The group leader, Molly Punderson, had clear blue eyes and wore her white hair pinned up in a bun. A former English teacher at the Milton Academy Girls’ School, she had recently retired and moved back to her native Stockbridge. Her great ambition was to write a grammar book. Molly knew a class clown when she saw one. “He was no great student,” she recalled of Rockwell. “He skipped classes, made amusing remarks, and livened up the sessions.”

At last Rockwell had found his feminine ideal: an older schoolteacher who had never lived with a man, and who in fact had lived with a female history teacher in a so-called Boston marriage for decades. When Molly moved into Rockwell’s home, she set up her bedroom in a small room across the hall from his. However unconventional the arrangement, and despite the apparent absence of sexual feeling, their relationship flourished. She satisfied his desire for intelligent companionship and required little in return. Once, asked by an interviewer to name the woman she most admired, she cited Jane Austen, explaining: “She contented herself with wherever she found herself.”

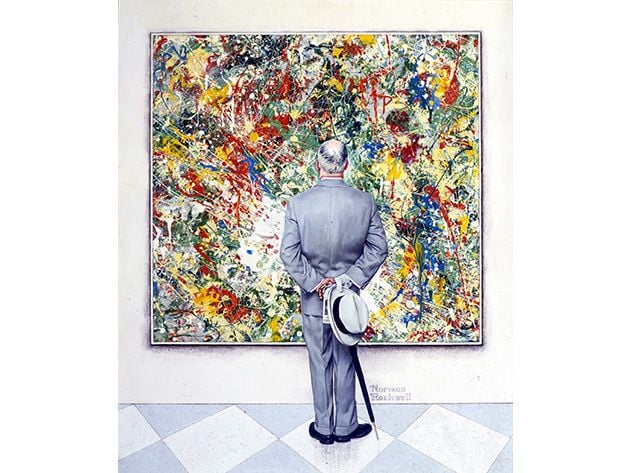

They were married on a crisp fall day, in October 1961, at St. Paul’s Church in Stockbridge. Molly arrived in Rockwell’s life in time to help him endure his final moments at the Post. He hinted at his fear of decline and obsolescence in his 1961 masterpiece, The Connoisseur. The painting takes us inside an art museum, where an older gentleman is shown from the back as he holds his fedora in his hand and contemplates a “drip” painting by Jackson Pollock. He’s a mystery man whose face remains hidden and whose thoughts are not available to us. Perhaps he is a stand-in for Rockwell, contemplating not only an abstract painting, but the inevitable generational change that will lead to his own extinction. Rockwell had nothing against the Abstract Expressionists. “If I were young, I would paint that way myself,” he said in a brief note that ran inside the magazine.

***

For decades, millions of Americans had looked forward to taking in the mail and finding a Rockwell cover. But starting in the ’60s, when the Post arrived, subscribers were more likely to find a color photograph of Elizabeth Taylor in emphatic eyeliner, decked out for her role in the film Cleopatra. The emphasis on the common man central to America’s sense of self in 20th-century America gave way, in the television-centered 1960s, to the worship of celebrities, whose life stories and marital crises replaced those of the proverbial next-door neighbor as subjects of interest and gossip.

Rockwell was aghast when his editors asked him to give up his genre scenes and start painting portraits of world leaders and celebrities. In September 1963, when the Post’s new art editor, Asger Jerrild, contacted Rockwell about illustrating an article, the artist wrote back: “I have come to the conviction that the work I now want to do no longer fits into the Post scheme.” It was, in effect, Rockwell’s letter of resignation.

On December 14, 1963, the Saturday Evening Post put out a memorial issue to honor a slain president. While other magazines ran grisly photographs of the assassination, the Post went with an illustration—it reprinted the Rockwell portrait of JFK that had run in 1960, before he was elected president. There he was again, with his blue eyes and thick hair and boyish Kennedy grin that seemed to promise that all would be well in America.

At the age of 69, Rockwell began working for Look magazine and entered a remarkable phase of his career, one devoted to championing the civil rights movement. Although he had been a moderate Republican in the ’30s and ’40s, he shifted to the left as he grew older; he was especially sympathetic to the nuclear disarmament movement that flourished in the late ’50s. Leaving the conservative Post was liberating for him. He began to treat his art as a vehicle for progressive politics. President Johnson had taken up the cause of civil rights. Rockwell, too, would help drive the Kennedy agenda forward. You might say he became its premier if unofficial illustrator.

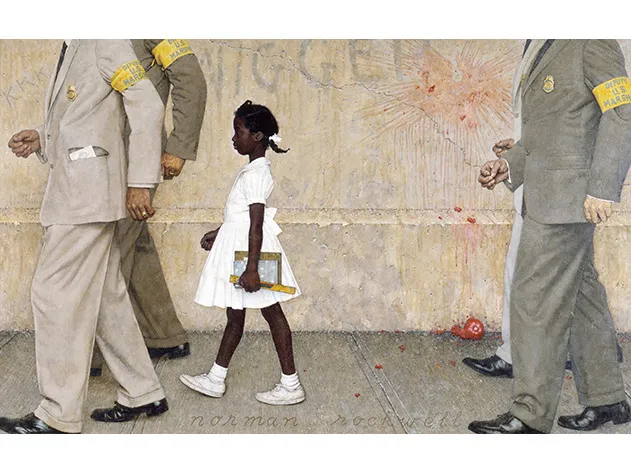

Rockwell’s first illustration for Look magazine, The Problem We All Live With, was a two-page spread that appeared in January 1964. An African-American girl—a 6-year-old in a white dress, a matching bow in her hair—is walking to school, escorted by four badge-wearing officers in lock step. Ruby Bridges, as most everyone now knows, was the first African-American to attend the all-white William Frantz elementary school in New Orleans, as a result of court-ordered desegregation. And Rockwell’s painting chronicled that famous day. On the morning of November 14, 1960, federal marshals dispatched by the U.S. Justice Department drove Ruby and her mother to her new school, only five blocks from their house. She had to walk by a crowd of crazy hecklers outside the school, most of them housewives and teenagers. She did this every day for weeks, and then the weeks became months.

It is interesting to compare Rockwell’s painting with the wire-service photographs on which it was loosely based. Even when he was depicting an event out of the headlines, Rockwell was not transcribing a scene but inventing one. To capture the problem of racism, he created a defaced stucco wall. It’s inscribed with a slur (“nigger”) and the initials KKK, the creepiest monogram in American history.

Many subscribers to the magazine, especially those who lived in the South, wrote furious letters to Look. But over time The Problem We All Live With would come to be recognized as a defining image of the civil rights movement in this country. Its influence was profound. Ruby would reappear in many guises in American culture, even in musical comedy. “That painting he did about the little black girl walking—that’s in Hairspray,” recalled John Waters, the director and writer of the film. “That inspired L’il Inez in Hairspray.” L’il Inez is the charismatic African-American girl in Baltimore who helps break down racial barriers by being the best dancer in town.

***

One afternoon in July 1968, Rockwell answered the phone in his studio and heard the voice at the other end talking intently about mounting a show of his work. He was taken by surprise and assumed the caller had confused him with the painter Rockwell Kent. “I’m sorry,” he said, “but I think you have the wrong artist.” The next morning, Bernie Danenberg, a young art dealer who was just opening a gallery on Madison Avenue in New York, drove up to Stockbridge. He convinced Rockwell to agree to an exhibition at his gallery—the first major show of Rockwell’s work in New York.

The opening reception was held at Danenberg’s on October 21, 1968. Dressed in his customary tweedy jacket, with a plaid bow tie, Rockwell arrived at the reception half an hour late and, by most accounts, felt embarrassed by the fuss. The show, which stayed up for three weeks, was ignored by most art critics, including those from the New York Times. But artists who had never thought about Rockwell now found much to admire. Willem de Kooning, who was then in his mid-60s and acclaimed as the country’s leading abstract painter, dropped by the show unannounced. Danenberg recalled that he especially admired Rockwell’s Connoisseur, the one in which an elderly gentleman contemplates a Pollock drip painting. “Square inch by square inch,” de Kooning announced in his accented English, “it’s better than Jackson!” Hard to know if the comment was intended to elevate Rockwell or demote Pollock.

With the rise of Pop Art, Rockwell was suddenly in line with a younger generation of painters whose work had much in common with his—the Pop artists had returned realism to avant-garde art after the half-century reign of abstraction. Warhol, too, came in to see the gallery show. “He was fascinated,” Danenberg later recalled. “He said that Rockwell was a precursor of the hyper-realists.” In the next few years, Warhol purchased two works by Rockwell for his private collection—a portrait of Jacqueline Kennedy, and a print of Santa Claus, who, like Jackie, was known by his first name and no doubt qualified in Warhol’s star-struck brain as a major celebrity.

Rockwell’s art, compared with that of the Pop artists, was actually popular. But in interviews, Rockwell always declined to describe himself as an artist of any sort. When asked, he would invariably demur, insisting he was an illustrator. You can see the comment as a display of humility, or you can see it as a defensive feint (he couldn’t be rejected by the art world if he rejected it first). But I think he meant the claim literally. While many 20th-century illustrators thought of commercial art as something you did to support a second, little-paying career as a fine artist, Rockwell didn’t have a separate career as a fine artist. He only had the commercial part, the illustrations for magazines and calendars and advertisements.

Rockwell died in 1978, at age 84, after a long struggle with dementia and emphysema. By now, it seems a bit redundant to ask whether his paintings are art. Most of us no longer believe that an invisible red velvet rope separates museum art from illustration. No one could reasonably argue that every abstract painting in a museum collection is aesthetically superior to Rockwell’s illustrations, as if illustration were a lower, unevolved life- form without the intelligence of the more prestigious mediums.

The truth is that every genre produces its share of marvels and masterpieces, works that endure from one generation to the next, inviting attempts at explication and defeating them in short order. Rockwell's work has manifested far more staying power than that of countless abstract painters who were hailed in his lifetime, and one suspects it is here for the ages.