Inside This Year’s Miss Navajo Pageant

Rest assured, this competition is far from just a beauty contest

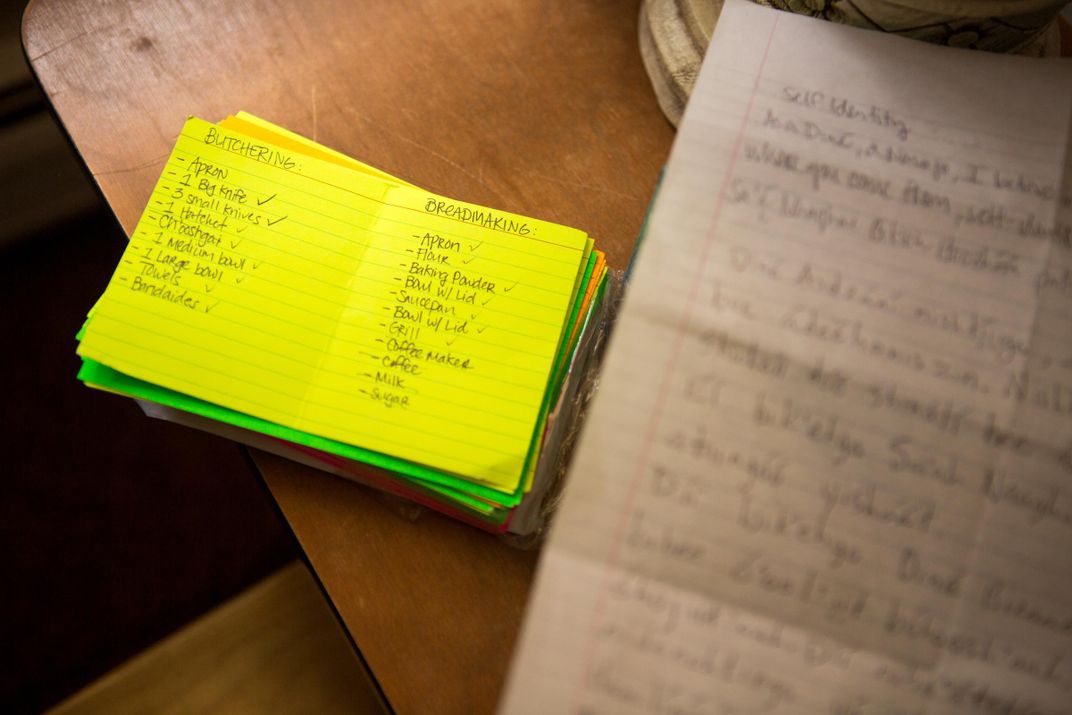

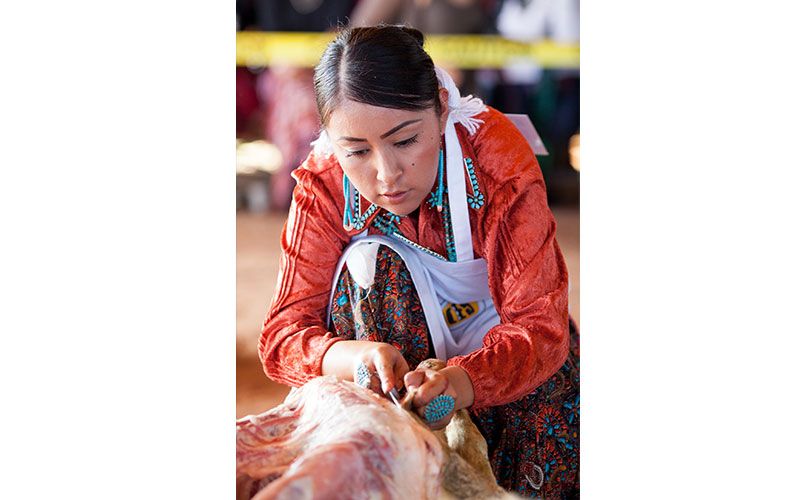

It is perhaps the least celebrated and most rigorous pageant in the world, and it is said, the only one where contestants must kill an animal. But in Window Rock, Arizona, five women with perfectly coiffed hair and jewel-toned, crushed velvet gowns lay out their knives in preparation for the first part of this year’s Miss Navajo pageant.

Several of the contestants have wound plastic wrap around their white moccasin leggings and tied on new cotton aprons— to avoid the blood stains. Finally, the sheep are carried in, placid and wide-eyed in the packed arena.

*****

Held every September since 1952 on the Navajo reservation, in an Arizona high desert town just over the New Mexico border, the pageant has reached cult status among girls in the Navajo culture. Organizers see this as a unique bridge between Navajo elders and the younger generations that otherwise might not have an incentive to follow the traditions.

Like any pageant, contestants in the Miss Navajo competition are vying for a place of honor in their culture’s value system. And maybe for this reason, it is the antithesis of Miss America-style contests.

“Miss America does the swim suit competition. But in the Miss Navajo pageant, we don’t show our bodies-- only our head and hands,” explains pageant coordinator Dinah Wauneka, who was instrumental in adding the butchering component to the competition in the late 1990s. “Butchering is the Navajo way of life. Within our culture, this is beauty.”

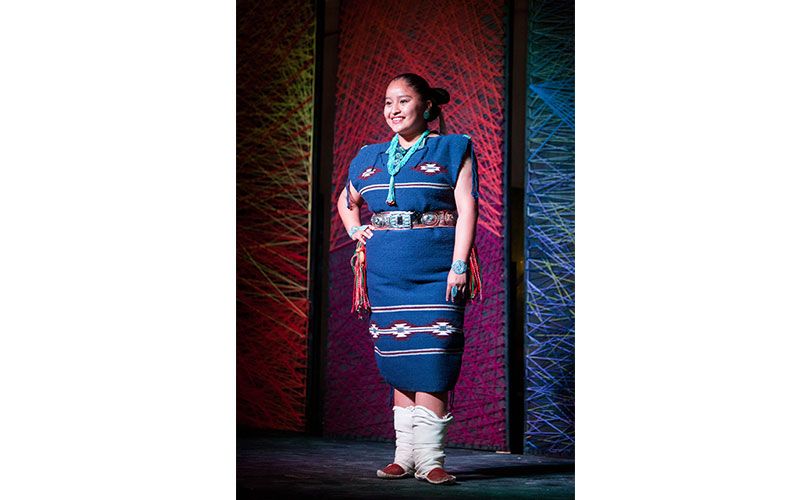

The stages of competition in the pageant are so challenging and demanding that only a handful of women even bother going for the title each year. For this year’s pageant, only 12 women, all between the ages of 18 and 25 as per the rules, picked up the application form. Of those, five were able to complete all of the eligibility requirements: Ann Marie Salt, 25, Alyson Jeri Shirley, 20, Crystal Littleben, 23, Farrah Fae Mailboy, 25, and Starlene Tsinniginnie, 25.

*****

At high noon the day before butchering, a slow trickle of pick-up trucks, road-dusted a burnt orange, arrive in the cracked asphalt parking lot of St. Michael’s Mission. With the hem of her blue sateen dress in hand, contestant Crystal Littleben hops out of the passenger seat of one and begins directing her father where to drop off her bins and garment bags. Directions are given in English peppered with words in the staccato Navajo (Diné) language. Families carry hardhats, kindling, barbeque racks, branches from a greasewood tree into the parish house-- a modest former abbey where the participants would be bunking for the week.

One essential qualification for the pageant is fluency in Diné language—a tongue completely unrelated to English. Vocal tone dictates meaning and verb conjugations change depending on the nature of the object: is it flat and flexible, solid and round, solid and thin? Most of the contestants agree that this fluency is the most challenging aspect of the competition.

One dissenter is contestant Alyson Shirley who began speaking Diné at age three. “I was raised by older Navajo ladies—my grandmother, mother, elders—around ceremonies and squaw dances. And they taught me this beautiful language.” She describes experiencing culture shock when she switched from a Diné language immersion program to a public junior high school and had to learn how to live in what she calls “the modern world.”

Inside the parish house, everyone is gathering in the room of Starlene Tsinniginnie as she unpacks. “I must have brought a dozen dresses,” she says. “I couldn’t decide.” Fortunately for her, she’ll have the chance to wear most of her wardrobe; during the three-day competition, the women will change outfits several times a day for various parts of the competition. Mothers, grandmothers, even the contestants themselves painstakingly constructed the outfits over past months.

Besides possessing a broad range of culturally relevant skills that they must demonstrate onstage, competitors must also know Navajo culture inside and out. Impromptu questions run the gamut from stories told by parents and grandparents to minute details of traditional daily life. What is the legend of Changing Woman, the diety who laid the foundation for the matriarchal Navajo way of life? Why are the tales of the coyote are only told in winter? What are your four clans? These questions are posed onstage, one day in Diné language, the next in English.

Contestant Farrah Mailboy remembers her first Miss Navajo pageant. When the judges asked her, ‘When a traditional ceremony is held for a male or female, which type of corn do they utilize?’” She had answered without hesitation: white corn for boys, yellow for girls.

Someone notices the stitches on the base of Starlene’s right thumb. A butchering injury. “Last month I probably butchered between 10 to 15 sheep,” she explains. “I put word out in my community that I would do it for free. It was great practice for this competition."

The sheep butchering competition requires participants to slaughter, skin and gut an adult Navajo-Churro ewe in just over an hour. They must simultaneously answer in Diné language, impromptu questions posed by roving judges who are assessing the contestants’ skills and knowledge of each part of the animal and how it is used.

On the morning of the butchering, the women have huddled just outside a sand-floor arena dense with spectators for a group blessing as the U.S. national anthem is sung in Diné language. Contestant Ann Marie Salt keeps her eyes closed long after the long prayer is over. Her mom and step-dad arrived just after sunrise to set up their camp chairs as close as possible to where she will be competing—as they will do for each event during the week.

She is intimidated but also relieved to know they are there. She has taken home six titles since she began competing in Native American competitions at age four, all with her family front and center. (Across the Navajo Nation, there are pageant competitions, referred to as “royalties,” for schools, colleges, agencies and states.) But today’s is the pinnacle of all of them for her.

Like political candidates, the contestants are asked to have a “platform,” or topic that they pledge to focus on should they wear the crown. For Salt, her platform reflects the concept of “hózhó,” a Diné term meaning a state of balance and order. She urges a focus on young women like her who have one foot in the Navajo world and one foot outside. “People see it as a disadvantage to grow up on a rural reservation, but I believe it’s an advantage for me and any person with dual identity. We need both perspectives.”

Following Navajo tradition, no part of a sheep is wasted. The women perform in unison, simultaneously working their knives as male volunteers help maneuver the animals into the right positions, hoisting them with roped onto beam-mounted hooks so the women can finish skinning and gutting. Cut the throat too quickly and the blood will not drain properly. Puncture the bladder and all of the meat is ruined. The contest is close.

After the end of this event—and those of the following two days— a winner is announced: Alyson Shirley.

Before accepting the crown, and the scholarships and other assorted gifts, Alyson reflected on why she entered the competition. “We got our culture from our deities. Our entire lives—even our government—is set up based on Navajo teachings. But we are forgetting that,” she emphasized. “Miss Navajo stands for hope. Even if you teach one person something, it’s enough because that person will go teach another person.”