What 200 Years of African-American Cookbooks Reveal About How We Stereotype Food

In a new book, food journalist Toni Tipton-Martin highlights African-American culinary history through hundreds of pages of recipes

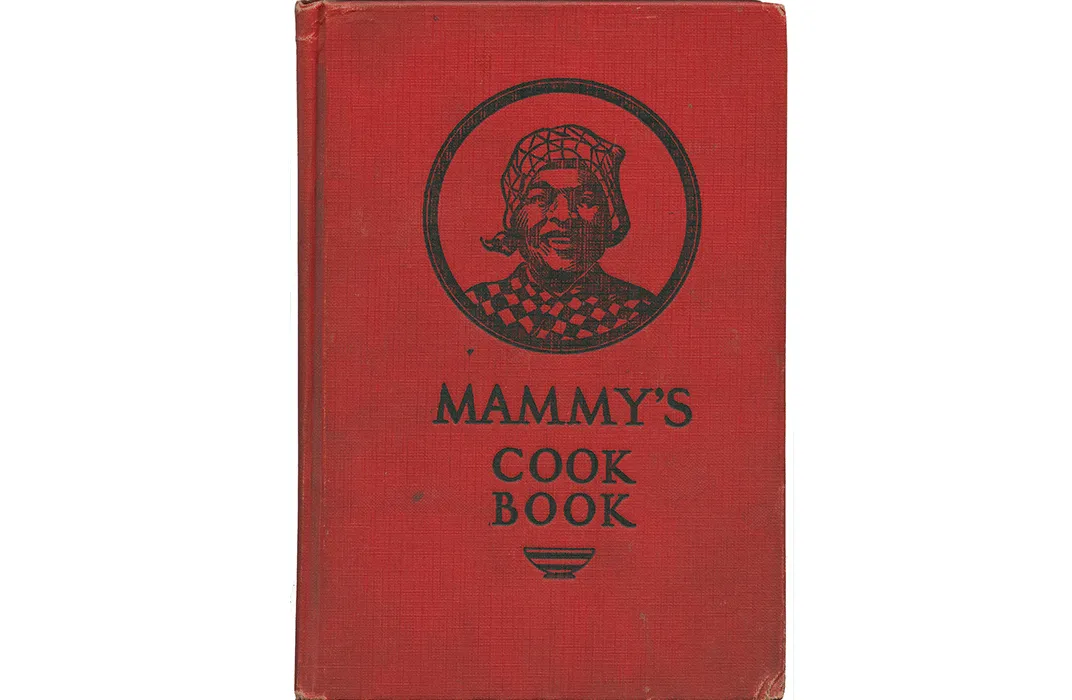

Aunt Jemima’s warm smile, pearl earrings and perfectly coiffed hair are easily recognizable in the breakfast foods aisle in grocery stores. But her initial stereotypical “mammy” look—obese, bandana-wearing, asexual—conceived by a pancake mix company in 1889, was just one of the many ways that American food culture misrepresented and coopted African American culinary traditions.

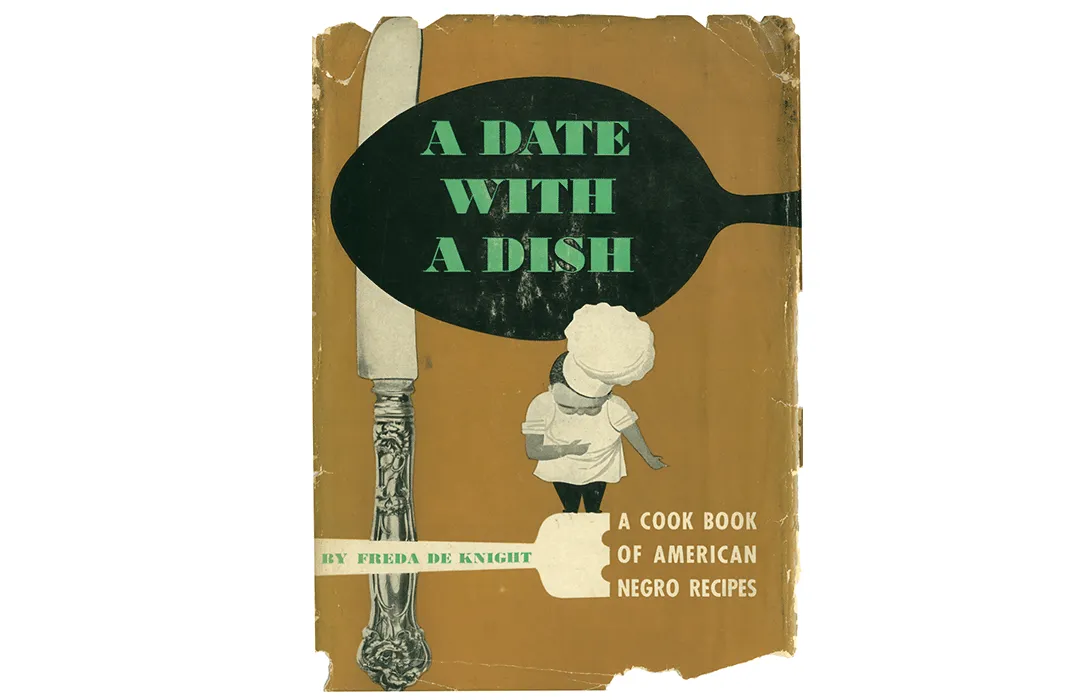

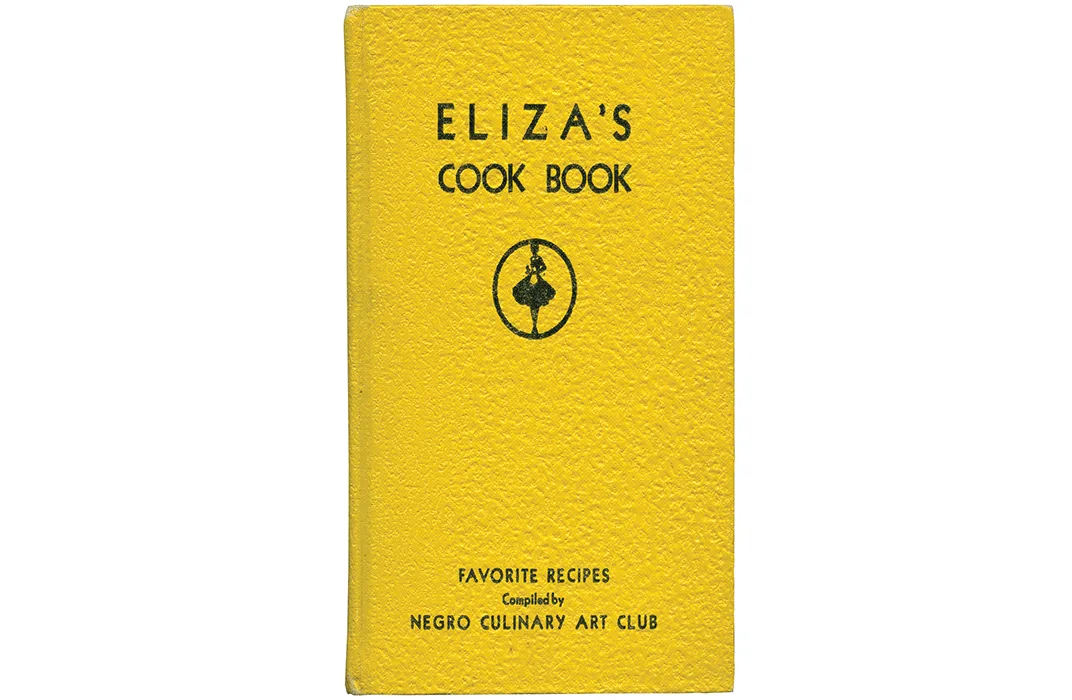

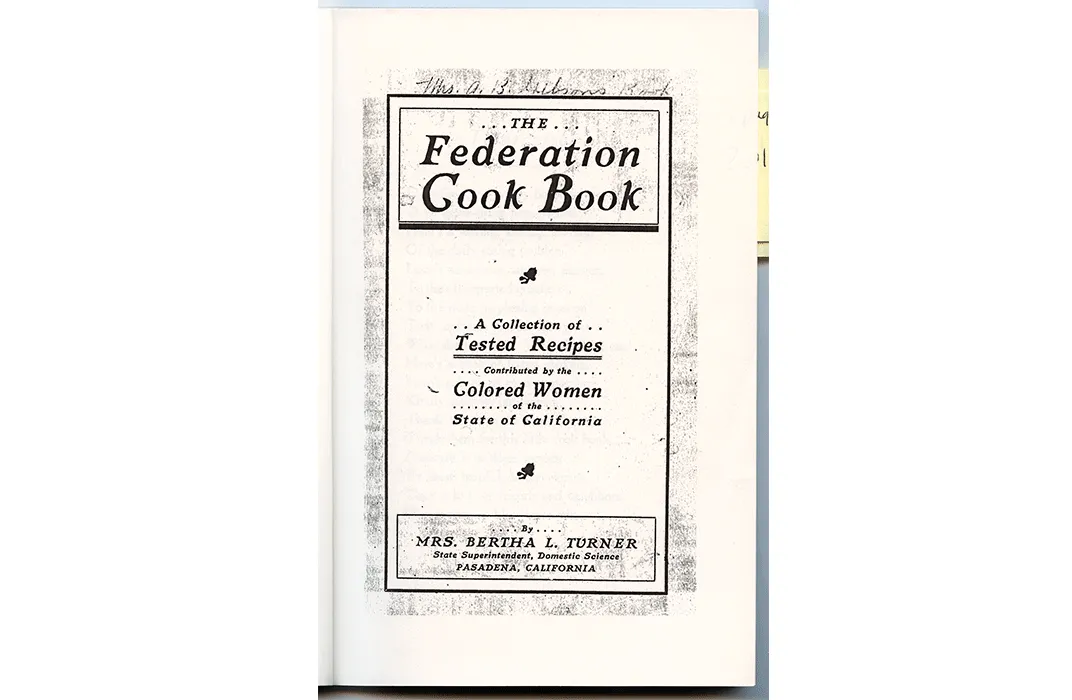

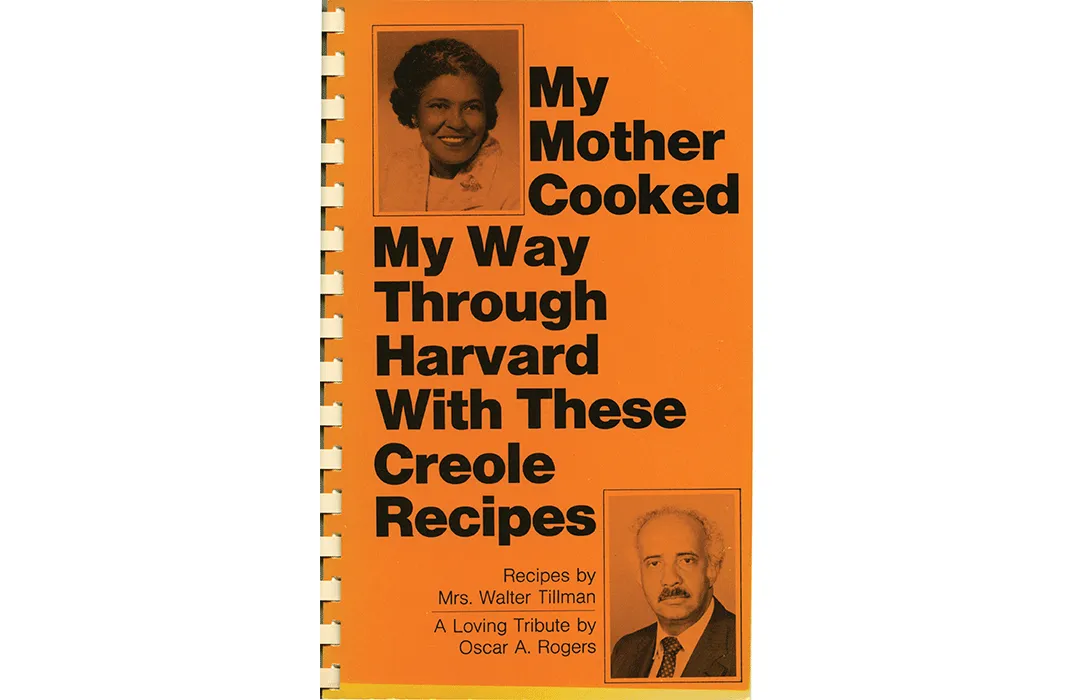

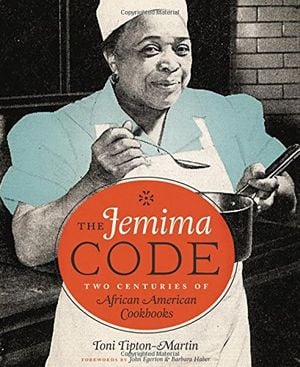

After collecting more than 300 cookbooks written by African American authors, award-winning food journalist Toni Tipton-Martin challenges those “mammy” characteristics that stigmatized African American cooks for hundreds of years in her new book The Jemima Code: Two Centuries of African American Cookbooks.

Tipton-Martin presents a new look at the influence of black chefs and their recipes on American food culture. Her goals are two-fold: to expand the broader community’s perception of African-American culinary traditions and to inspire African Americans to embrace their culinary history.

The earliest cookbooks featured in The Jemima Code date to the mid-19th century when free African Americans in the North sought avenues for entrepreneurial independence. In 1866, Malinda Russell self-published the first complete African-American cookbook, , which included 250 recipes for everything from medical remedies to pound cake.

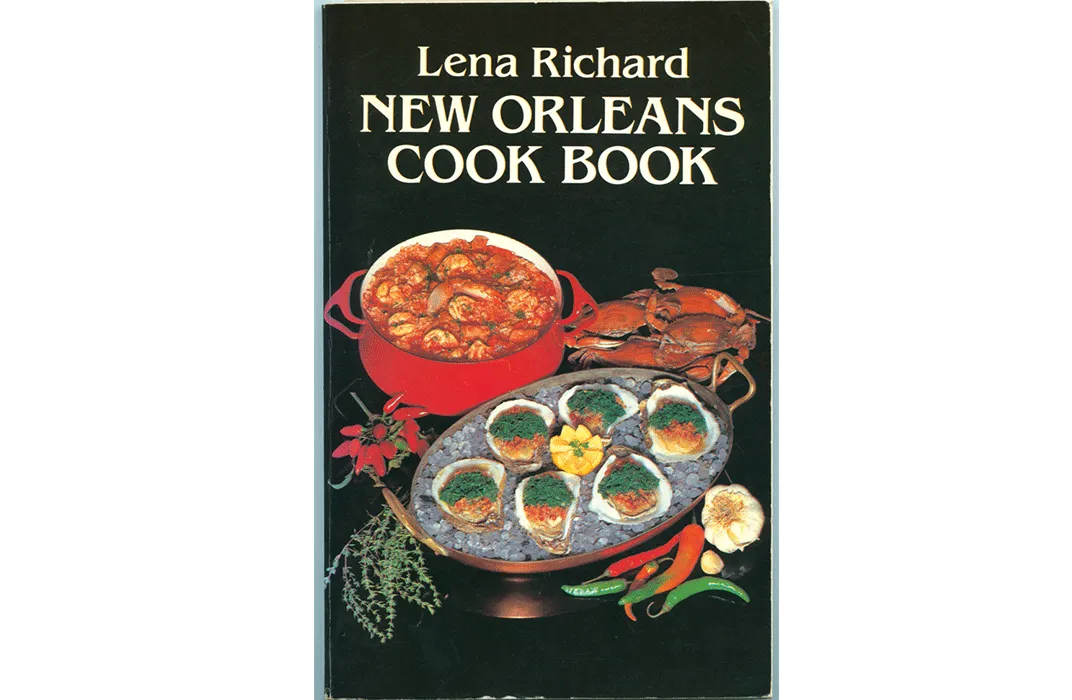

Recipe books of the early to mid-20th century catered to the multicultural, European-inspired palette of the white and black middle class. Lena Richard’s New Orleans Cook Book, for instance, includes recipes such as shrimp remoulade and pain perdu that “put the culinary art within the reach of every housewife and homemaker.”

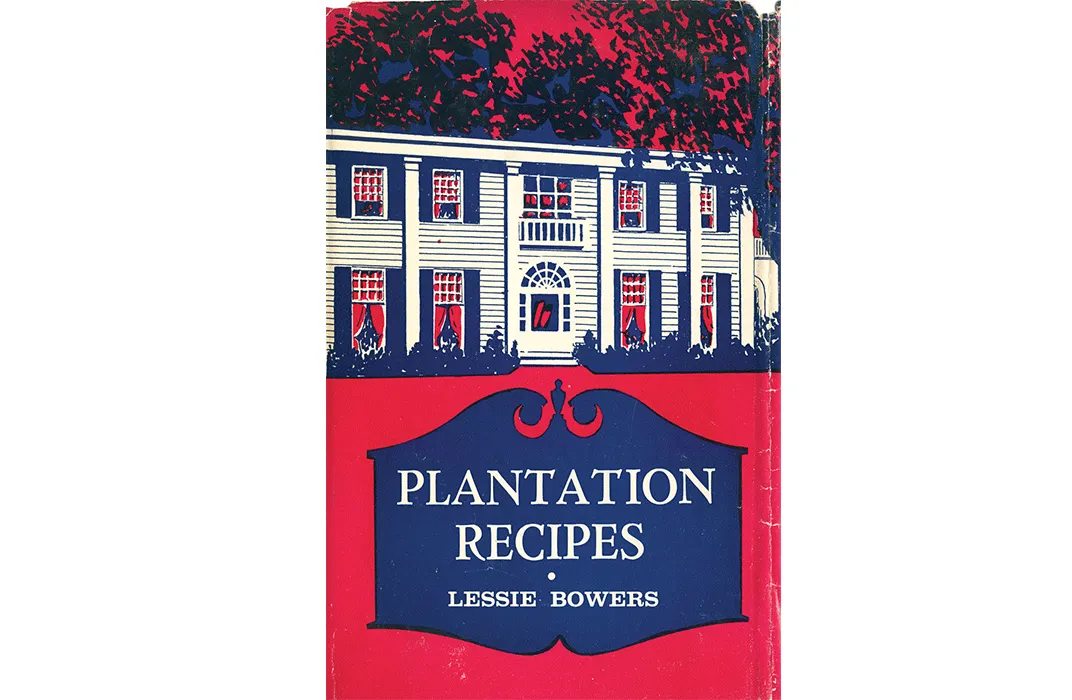

And many cookbooks featured recipes developed by African-American servants for the tastes of their white employers. Mammy’s Cook Book, which was self-published in 1927 by a white woman who credits all of the recipes to the black caretaker of her childhood, includes recipes for egg custards and Roquefort and tomato salad.

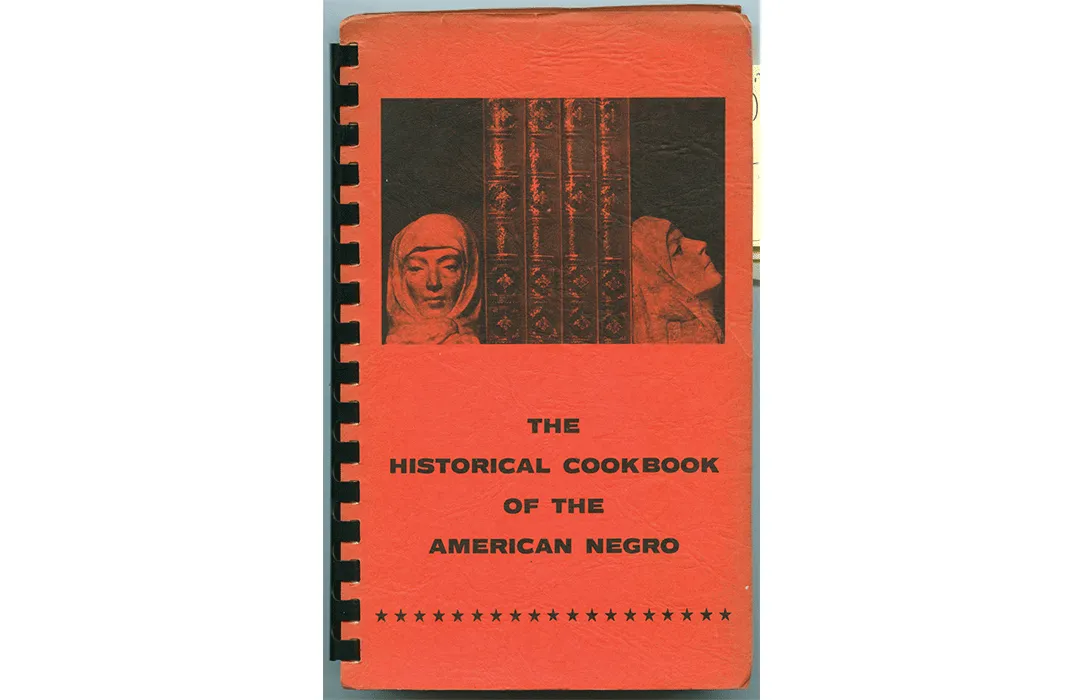

Cookbooks of the 1950s reflected the passionate spirit for social change; Civil Rights Movement activists used food as a way to promote pride in African-American identity. The Historical Cookbook of the American Negro of 1958 from the National Council of Negro Women, for example, paid homage to George Washington Carver with a section of peanut inspired recipes that included peanut ice cream.

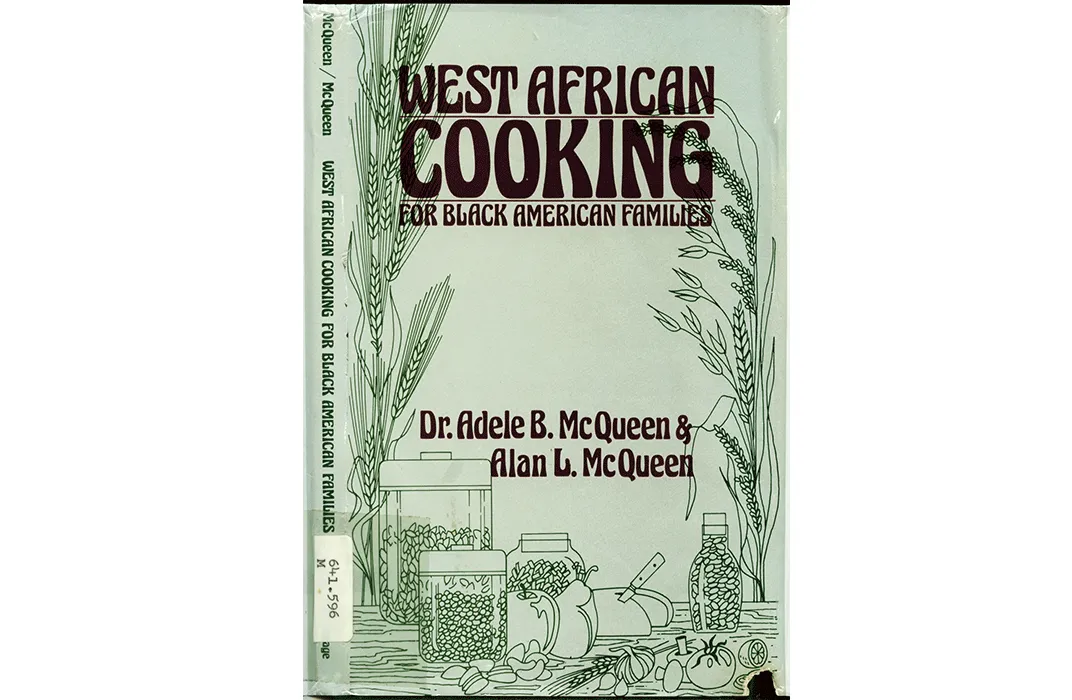

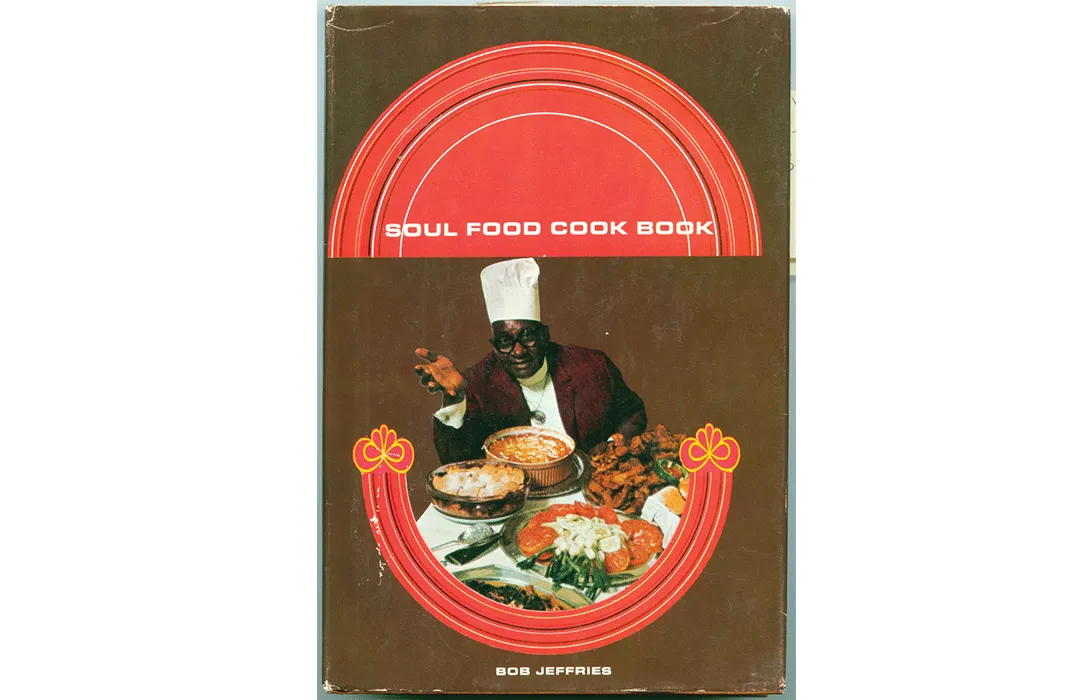

As affection for black pride grew in the 1960s, soul food that had come to urban areas during the Great Migration a generation earlier rose in the culinary esteem as chefs called on those traditions for their own menus. Recipes for collard greens, buttermilk biscuits and hushpuppies were staples in Bob Jeffries’ Soul Food Cook Book. In later years, soul food revived itself by extending its black pride to the culinary customs of the African diaspora in cookbooks like the 1982 West African Cooking for Black American Families, which included recipes for gumbo and sweet potato pie.

We spoke with Tipton-Martin about her new book and the cookbooks that her research uncovered. (The following has been edited for length.)

Why are cookbooks important to understanding a culture?

Scholars have begun to consider cookbooks an important resource because in some communities, that was the only voice that women had; the only place to record names, activities, their own personal file. And especially for African Americans, who had few other outlets for creative energy, the cookbook has provided their own word without the need for interpretation.

In the introduction to the book you refer to yourself as a casualty of the “Jemima Code.” What do you mean by that?

I was a victim of the idea that my food history was not important. And so I had no interest in practicing it, preserving it. I didn’t even really see its value. Let’s start from there. It’s not that I was actively disregarding it, it’s just that subconsciously I had bought into the system that said your cooks weren’t important and they don’t matter.

You write about cookbook authors and cooks who embodied Civil Rights principles. What role did cooks and food have in the Civil Rights movement?

When we think about the conveniences that we have today with food on every street corner, it’s hard to imagine traveling in the rural south for miles [as Civil Rights workers did] and finding nothing to eat. And then when you do encounter a place where you can get a bite to eat, you’re forbidden to eat there. So cooks made sandwiches and provided food in a sort of Underground Railroad way, where there were outposts where people provided meals to Civil Rights workers. There were women who would work all day on a job and then would come in and whatever meager ingredients she had to share with her family she would also share those with the broader community. And so it’s just part of the selflessness of who they were and who they had always been as nurturers and caretakers.

How do you think African American food culture is changing?

I’m not sure that it’s changing at all. What is changing is the perception of African-American food culture. The broader community has narrowly defined what it means to cook African-American food and so modern chefs are not doing anything different than we see The Jemima Code chefs did, which is interpreting classical technique with whatever the local ingredients are.

What did you learn about yourself and your own history through the writing of this book?

It unlocked memories and mysteries for me that I had not really come to grips with or shared in our food history. So I learned about family members that were restaurateurs or had worked in the food industry as chefs. But that conversation hadn’t come up under other circumstances because again I was part of that generation of people whose parents wanted us to move into areas with more upward mobility and less stigma than the service industry. So it was a good tool.

My experience is what I hope to have happen in the broader community after reading The Jemima Code. More revelations of who we really are so we can treat one another as individuals rather than as an entire group that all African Americans look like this and act like this and cook like this. That food is just one way to communicate what political messengers or educators or other institutions have not been able to accomplish.

Which of these cookbooks impacted you the most?

Even though Malinda Russell is not the first book in the series, she is the first woman in the series in 1866. And she was a single mother, she understood her purpose and what she was accomplishing through her food and at the table. And she left us enough tools in her material that we can write in multiple directions from just the little introduction that she left us. We know that she was an apprentice, which is not a term we use to refer to these people. So I guess if I had to articulate why one sticks out, she would be it.

What is your next book?

It’s called The Joy of African American Cooking and it’s 500 recipes adapted from the books of The Jemima Code. It’s projected to be published in 2016.

Of all of those recipes, which are your favorites or which are the ones you frequently cook yourself?

I love to bake, and so I would have to say that a lot of the biscuits and of course all of the delicious sweets are my favorite. I recently posted some biscuits that were made into a pinwheel that were filled with cinnamon and sugar, like a cinnamon roll but they’re made with biscuit dough and they were—we ate the whole pan!

What do you hope the general public gets out of the book?

I hope that people will take the time to get to know a new story for African-American cooks and develop a respect and appreciation that enables people to open businesses that will be visited, patronized. I hope it expands our thinking so that more people can buy and sell cookbooks. I hope that changing the image will make it possible for African Americans to participate and for other nationalities to participate with them, whether it’s tasting the food, buying the books, eating at the restaurants or just cooking it at home.

When we spoke earlier, you told me you hope that the book can be catalyst for racial reconciliation. What do you mean by that?

What the book demonstrates is that there is diversity among African-American cooks in terms of who they were, how they work, where they work. And part of the problem with prejudice and stereotyping is we see a person or a particular group based on one encounter. And that changes how we see a whole community.

My hope is that when people see this group differently than they had ever thought of them then they’ll also be able to apply that knowledge to other parts of other communities. I want to undo racism one experience at a time and cooking is a way to do that. We all share the common ground of cooking. The table has always been a place where people can find common ground.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_0154.JPG.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_0154.JPG.jpeg)