Larger than Life

Whether denouncing France’s art establishment or challenging Napoleon III, Gustave Courbet never held back

Painter, provocateur, risk taker and revolutionary, Gustave Courbet might well have said, "I offend, therefore I am." Arguably modern art's original enfant terrible, he had a lust for controversy that makes the careers of more recent shockmeisters like Jeff Koons, Damien Hirst and Robert Mapplethorpe seem almost conventional. As a rebellious teenager from a small town in eastern France, Courbet disregarded his parents' desire for him to study law and vowed, he wrote, "to lead the life of a savage" and free himself from governments. He did not mellow with age, disdaining royal honors, turning out confrontational, even salacious canvases and attacking established social values when others of his generation were settling into lives cushioned with awards and pensions.

Courbet arrived in Paris in 1839 at the age of 20 intent on studying art. Significantly, considering his later assault on the dominance and rigidity of the official art establishment, he did not enroll in the government-sanctioned Academy of Fine Arts. Instead he took classes in private studios, sketched at museums and sought advice and instruction from painters who believed in his future. Writing to his parents in 1846 about the difficulty of making a name for himself and gaining acceptance, he said his goal was "to change the public's taste and way of seeing." Doing so, he acknowledged, was "no small task, for it means no more and no less than overturning what exists and replacing it."

As the standard-bearer of a new "realism," which he defined as the representation of familiar things as they are, he would become one of the most innovative and influential painters of mid-19th-century France. His dedication to the portrayal of ordinary life would decisively shape the sensibilities of Manet, Monet and Renoir a generation later. And Cézanne, who praised the older artist for his "unlimited talent," would embrace and build on Courbet's contention that brushwork and paint texture should be emphasized, not concealed. In addition, by holding his own shows and marketing his work directly to the public, Courbet set the stage for the Impressionists in another way. After their paintings were repeatedly rejected by the Paris Salon (the French government's all-important annual art exhibition), Monet, Renoir, Pissarro and Cézanne organized their own groundbreaking show in 1874. It was at that exhibition that a critic derisively dubbed the group "Impressionists." Who knows, wrote art critic Clement Greenberg in 1949, "but that without Courbet the impressionist movement would have begun a decade or so later than it did?"

Courbet worked in every genre, from portraiture, multi-figural scenes and still lifes to landscapes, seascapes and nudes. He did so with a surpassing concern for accurate depiction, even when that meant portraying impoverished women or laborers engaged in backbreaking tasks—a radical approach at a time when his peers were painting fanciful scenes of rural life, stories drawn from mythology and celebrations of aristocratic society. Courbet's women were fleshy, often stout. His laborers appeared tired, their clothes torn and dirty. "Painting is an essentially concrete art," he wrote in a letter to prospective students in 1861, "and can consist only of the representation of things both real and existing."

He also developed the technique of using a palette knife—and even his thumb—to apply and shape paint. This radical method—now commonplace—horrified conservative viewers accustomed to seeing glossy paint smoothed onto the surface of a picture and was ridiculed by many critics. The sensuous rendering and eroticism of the women in Courbet's canvases further scandalized the bourgeoisie.

These once-controversial paintings are part of a major retrospective of Courbet's work now at New York City's Metropolitan Museum of Art (through May 18). The exhibition, which opened last year at the Grand Palais in Paris and will continue on to the Musée Fabre in Montpellier, France, features more than 130 paintings and drawings. Nearly all of Courbet's important canvases have been included, except A Burial at Ornans (p. 86) and The Painter's Studio (above)—the two masterpieces on which his early reputation rests—because they were deemed too large and too fragile to travel.

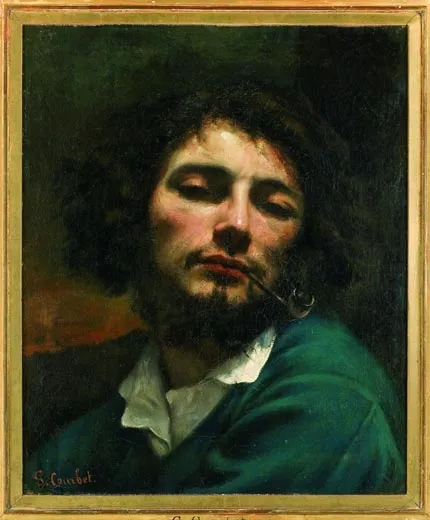

A fresh—and revelatory—dimension of the exhibition is its concentration on the face that Courbet presented to the world. A series of arresting self-portraits from the 1840s and early 1850s advertise him as an alluring young man in the Byronic mode, with long hair and liquid brown eyes. One of them, The Desperate Man, has never been seen in the United States. In it, Courbet portrays himself in a state of frenzy, confronting the viewer with a mesmerizing stare. Few artists since Caravaggio could have brought off a portrait so emotionally extreme, composed of equal parts aggression and startling charm.

The early self-portraits, says the Met's Kathryn Calley Galitz, one of the show's curators, "disclose that Courbet was emphatically responding to Romanticism, which makes his later shift to Realism even more significant." These images also record a youthful slenderness that would prove fleeting. Courbet's appetite for eating and drinking was as gargantuan as his hunger for fame. ("I want all or nothing," he wrote to his parents in 1845; "...within five years I must have a reputation in Paris.") As he put on weight, he came to resemble nothing so much as what he was—an intellectual, political and artistic battering ram.

Courbet's acquaintances in Paris were under the impression—craftily abetted by the artist himself—that he was an ignorant peasant who had stumbled into art. In truth, Jean Désiré-Gustave Courbet, though provincial, was an educated man from an affluent family. He was born in 1819 in Ornans, in the mountainous Franche-Comté region near the Swiss border, to Régis and Sylvie Oudot Courbet. Régis was a prosperous landowner, but anti-monarchical sentiments infused the household. (Sylvie's father had fought in the French Revolution.) Gustave's younger sisters—Zoé, Zélie and Juliette—served as ready models for their brother to draw and paint. Courbet loved the countryside where he grew up, and even after he moved to Paris he returned nearly every year to hunt, fish and derive inspiration.

At age 18, Courbet was sent to college in Besançon, the capital city of the Franche-Comté. Homesick for Ornans, he complained to his parents about cold rooms and bad food. He also resented wasting time in courses in which he had no interest. In the end, his parents agreed to let him live outside the college and take classes at a local art academy.

In the autumn of 1839, after two years in Besançon, Courbet journeyed to Paris, where he began studying with Baron Charles von Steuben, a history painter who was a regular exhibitor at the Salon. Courbet's more valuable education, however, came from observing and copying Dutch, Flemish, Italian and Spanish paintings in the Louvre.

His first submission to the Salon, in 1841, was rejected, and it wasn't until three years later, in 1844, that he would finally have a painting, Self-Portrait With Black Dog, selected for inclusion. "I have finally been accepted to the Exhibition, which gives me the greatest pleasure," he wrote to his parents. "It is not the painting that I would most have wanted to have accepted but no matter....They have done me the honor of giving me a very beautiful location....a place reserved for the best paintings in the Exhibition."

In 1844 Courbet began work on one of his most acclaimed self-portraits, The Wounded Man (p. 3), in which he cast himself as a martyred hero. The portrait, which exudes a sense of vulnerable sexuality, is one of Courbet's early explorations of erotic lassitude, which would become a recurring theme. In Young Ladies on the Banks of the Seine of 1856-57 (opposite), for instance, two women—one dozing, one daydreaming—are captured in careless abandon. The sleeping woman's disarrayed petticoats are visible, and moralists of the time were offended by Courbet's representation of the natural indecorousness of sleep. One critic called the work "frightful." In 1866 Courbet outdid even himself with Sleep, an explicit study of two nude women asleep in each other's arms. When the picture was shown in 1872, the commotion surrounding it was so intense that it was noted in a police report, which became part of a dossier the government was keeping on the artist. Courbet, a critic observed, "does democratic and social painting—God knows at what cost."

In 1848 Courbet moved into a studio at 32 rue Hautefeuille on the Left Bank and started hanging out in a neighborhood beer house called the Andler Keller. His companions—many of whom became portrait subjects—included the poet Charles Baudelaire, art critic Champfleury (for many years, his champion in the press) and philosopher Pierre-Joseph Proudhon. They encouraged Courbet's ambitions to make unidealized pictures of everyday life on the same scale and with the same seriousness as history paintings (large-scale narrative renderings of scenes from morally edifying classical and Christian history, mythology and literature). By the early 1850s, Courbet was enjoying the patronage of a wealthy collector named Alfred Bruyas, which gave him the independence and means to paint what he wanted.

Few artists have been more sensitive to, or affected by, political and social changes than Courbet. His ascent as a painter was tied to the Revolution of 1848, which led to the abdication of King Louis-Philippe in February of that year. The succeeding Second Republic, a liberal provisional government, adopted two key democratic reforms—the right of all men to vote and to work. In support of these rights, Courbet produced a number of paintings of men and women laboring at their crafts and trades. In this more tolerant political climate, some of the Salon's requirements were eliminated, and Courbet was able to show ten paintings—a breakthrough for him—in the 1848 exhibition. The following year, one of his genre scenes of Ornans won a gold medal, exempting him from having to submit his work to future Salon juries.

Starting in the early 1840s, Courbet lived with one of his models, Virginie Binet, for about a decade; in 1847 they had a child, Désiré-Alfred Emile. But when the couple separated in the winter of 1851-52, Binet and the boy moved away from Paris, and both mistress and son, who died in 1872, seem to have disappeared from the artist's life. After Binet, Courbet avoided lasting entanglements. "I am as inclined to get married," he had written his family in 1845, "as I am to hang myself." Instead, he was ever in the process of forming, hoping for or dissolving romantic attachments. In 1872, while back in Ornans, Courbet, then in his early 50s, wrote a friend about meeting a young woman of the sort that he "had been seeking for twenty years" and of his hopes of persuading her to live with him. Puzzled that she preferred marriage with her village sweetheart to his offer of "the brilliant position" that would make her "indisputably the most envied woman in France," he asked the friend, who was acting as a go-between, to find out if her answer was given with her full knowledge.

Courbet's status as a gold-medal winner allowed A Burial at Ornans (which was inspired by the funeral of his great-uncle in the local cemetery) to be shown at the 1851 Salon, despite the critics who derided its frieze-like composition, subject matter and monumentality (21 by 10 feet). Some 40 mourners, pallbearers and clergy—actual townspeople of Ornans—appear in the stark scene. This provided a radically different visual experience for sophisticated Parisians, for whom rustics and their customs were more likely to be the butt of jokes than the subjects of serious art. One writer suggested that Courbet had merely reproduced "the first thing that comes along," while another compared the work to "a badly done daguerreotype." But François Sabatier, a critic and translator, understood Courbet's achievement. "M. Courbet has made a place for himself...in the manner of a cannon ball which lodges itself in a wall," he wrote. "Despite the recriminations, the disdain, and the insults which have assailed it, despite even its flaws, A Burial at Ornans will be classed...among the most remarkable works of our time."

In December 1851, Louis Napoleon (a nephew of the French emperor and the elected president of the Second Republic) staged a coup d'état and declared himself Emperor Napoleon III. Under his authoritarian rule, artistic freedom was limited and an atmosphere of repression prevailed—the press was censored, citizens were put under surveillance and the national legislature was stripped of its power. Courbet's tender study of his three sisters giving alms to a peasant girl, Young Ladies of the Village, was attacked by critics for the threat to the class system that it appeared to provoke. "It is impossible to tell you all the insults my painting of this year has won me," he wrote to his parents, "but I don't care, for when I am no longer controversial I will no longer be important."

Courbet drew even more ire in 1853 with The Bathers, a posterior view of a generously proportioned woman and her clothed servant in a forest. Critics were appalled; the naked bather reminded one of them of "a rough-hewn tree-trunk." The romantic painter Eugène Delacroix wrote in his journal: "What a picture! What a subject! The commonness and the uselessness of the thought are abominable."

Courbet's most complex work, The Painter's Studio: A Real Allegory Summing up a Seven-Year Phase of My Artistic Life (1855), represented his experiences and relationships since 1848, the year that marked such a turning point in his career. On the left of the painting are victims of social injustice—the poor and the suffering. On the right stand friends from the worlds of art, literature and politics: Bruyas, Baudelaire, Champfleury and Proudhon are identifiable figures. In the center is Courbet himself, working on a landscape of his beloved Franche-Comté. A nude model looks over his shoulder and a child gazes raptly at the painting in progress. Courbet portrays the studio as a gathering place for the whole of society, with the artist—not the monarch or the state—the linchpin that keeps the world in rightful balance.

The 1855 Exposition Universelle, Paris' answer to London's Crystal Palace exhibition of 1851, was the art event of the decade in France. Examples of contemporary art movements and schools from 28 countries—as long as they met Napoleon III's criteria for being "pleasant and undemanding"—were to be included. Count Emilien de Nieuwerkerke—the Second Empire's most powerful art official—accepted 11 of 14 paintings Courbet submitted. But three rejections, which included The Painter's Studio and A Burial at Ornans, were three too many. "They have made it clear that at any cost my tendencies in art must be stopped," the artist wrote to Bruyas. I am "the sole judge of my painting," he had told de Nieuwerkerke. "By studying tradition I had managed to free myself of it...I alone, of all the French artists of my time, [have] the power to represent and translate in an original way both my personality and my society." When the count replied that Courbet was "quite proud," the artist shot back: "I am amazed that you are only noticing that now. Sir, I am the proudest and most arrogant man in France."

To show his contempt, Courbet mounted an exhibition of his own next door to the Exposition. "It is an incredibly audacious act," Champfleury wrote approvingly to novelist George Sand. "It is the subversion of all institutions associated with the jury; it is a direct appeal to the public; it is liberty." After Delacroix visited Courbet's Pavilion of Realism (as the rebellious artist titled it), he called The Painter's Studio "a masterpiece; I simply could not tear myself away from the sight of it." Baudelaire reported that the exhibition opened "with all the violence of an armed revolt," and another critic called Courbet "the apostle of ugliness." But the painter's impact was immediate. The young James Whistler, recently arrived from the United States to study art in Paris, told an artist friend that Courbet was his new hero, announcing, "C'est un grand homme!" ("He is a great man!").

By the 1860s, through exhibitions in galleries in France and as far away as Boston, Courbet's work was selling well. Dealers in France vied to exhibit his still lifes and landscapes. And his poignant hunting scenes, featuring wounded animals, also found a following in Germany. Despite his continued opposition to Napoleon III, Courbet was nominated to receive the French Legion of Honor in 1870, an attempt, perhaps, to shore up the emperor's prestige on the eve of the Franco-Prussian War. Although Courbet had once hoped for the award, his "republican convictions," he now said, prevented him from accepting it. "Honor does not lie in a title or a ribbon; it lies in actions and the motives for actions," he wrote. "I honor myself by remaining faithful to my lifelong principles; if I betrayed them, I should desert honor to wear its mark."

Courbet's gesture impressed political insurgents. In 1871, after Napoleon III was defeated by the Germans, Parisian revolutionaries known as the Commune began reorganizing the city along socialist lines; Courbet joined the movement. He was put in charge of the city's art museums and successfully protected them from looters. He declared, however, that the Vendôme Column, a monument to Napoleon Bonaparte and an emblem of French imperialism, was devoid of artistic value and should be dismantled and re-erected elsewhere. The column was toppled on May 16, 1871. When the Commune was crushed and the Third Republic established a few weeks later, Courbet was held responsible for the column's destruction, even though the Commune had officially decided its fate before the artist's appointment and had executed the decree after his resignation. Arrested in June 1871, Courbet was fined and later sentenced to six months in prison, but he became ill while incarcerated and was sent to a clinic to recuperate. Ever defiant, he bragged to his sisters and friends that his troubles had increased both his sales and his prices. Some artists, jealous of his success and angered by his boasting, lashed out. "Courbet must be excluded from the Salons," contended the painter Ernest Meissonier. "Henceforth, he must be dead to us."

In 1873, the Third Republic wanted to reinstall the column and Courbet was ordered to pay all reconstruction costs. Lacking the estimated hundreds of thousands of francs it would cost and facing the possible seizure of his lands and paintings, he fled to Switzerland, where he spent the last four years of his life in exile, drowning himself in alcohol and hoping for a pardon. In May 1877, the government decreed that the artist owed his country 323,000 francs (about $1.3 million today), payable in yearly installments of 10,000 francs for the next 32 years. Courbet died on December 31, 1877, the day before the first installment was due. He was 58. The cause of death was edema, presumably the result of his excessive drinking. In 1919, his remains were transferred from Switzerland to the same cemetery in Ornans that he had once painted with such bravado and conviction.

New York-based author and art historian Avis Berman wrote about Edward Hopper in the July 2007 issue of Smithsonian.