Lost & Found

Ancient gold artifacts from Afghanistan, hidden for more than a decade, dazzle in a new exhibition

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/lostandfound_sept08_631.jpg)

Kabul, 2004

On a hot day in late april some 30 archaeologists, cultural officials and National Museum of Afghanistan staffers crammed into a small office at the city's Central Bank. Before them was a safe, one of six containing a cache of 2,000-year-old gold jewelry, ornaments and coins from the former region of Bactria in northern Afghanistan. Fifteen years before, the treasure, known as the Bactrian Hoard, had been secretly removed from the museum and stashed in the bank's underground vault under the supervision of Omara Khan Masoudi, the museum's director. The handful of museum employees responsible for hiding it had risked their lives to protect the treasure from warring factions and looters in the wake of the 1989 withdrawal of Soviet forces from Afghanistan. In the years since, conflicting rumors had circulated about the objects. One version had departing Soviet troops spiriting them away to Moscow. Another held that they had been melted down to buy arms. A third had them sold on the black market. Now that the political situation had improved and an agreement had been reached with the National Geographic Society to conduct an inventory, the Bactrian gold would at last be brought back into public view.

Since keys to the safe could not be found, a locksmith had been summoned. It took just 15 minutes for him to penetrate it with a circular saw. As sparks flew, Fredrik Hiebert, an American archaeologist working for the National Geographic Society, held his breath.

"I could just imagine opening the safe to find a big, hot lump of melted gold," he recalls. "It was an incredibly emotional moment."

Four years later, many of the artifacts—none of which were damaged in the opening of the safes—are the centerpieces of an exhibition at the National Gallery of Art, with Hiebert as guest curator, "Afghanistan: Hidden Treasures From the National Museum, Kabul" will travel to the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco (October 24, 2008-January 25, 2009), the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (February 22-May 17, 2009) and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City (June 23-September 20, 2009).

Unearthed from four ancient sites, the show's 228 works (including more than 100 pieces from the Bactrian trove) reveal the extent of links in the years 2200 b.c. to a.d. 200 among Hellenistic, Persian, Indian, Chinese and nomadic cultures along the ancient Silk Road—trading routes stretching 5,000 miles from the Mediterranean Sea to China. A knife handle embossed with an image of a Siberian bear, for instance, and a diadem (opposite) festooned with gilded flowers similar to ones found in Korea both indicate far-flung stylistic influences.

Afghanistan's deputy culture minister, Omar Sultan, a former archaeologist, says he hopes the exhibition will call attention to the beleaguered country's untapped rich archaeological heritage. He estimates that only 10 percent of its sites have been discovered, though many, both excavated and not, have been looted. "Afghanistan is one of the richest—and least-known—archaeological regions in the world," says Hiebert. "The country rivals Egypt in terms of potential finds."

Hill of Gold

Fashioned into cupids, dolphins, gods and dragons and encrusted with semiprecious stones, the Bactrian pieces were excavated in 1978-79 from the graves of six wealthy nomads—Saka tribesmen from Central Asia, perhaps, or the Yuezhi from northwest China—at a site called Tillya Tepe ("Hill of Gold") in northern Afghanistan. The 2,000-year-old artifacts exhibit a rare blend of aesthetic influences (from Persian to Classical Greek and Roman) and a high level of craftsmanship. The diadem, a five-inch-tall crown of hammered gold leaf, conveniently folds for travel, and a thumb-size gold figure of a mountain sheep is delicately incised with curving horns and flaring nostrils.

Viktor Sarianidi, the Moscow archaeologist who led the joint Soviet-Afghan team that uncovered the graves, compares the impact of the find to the 1922 discovery of Tutankhamen's tomb. "The gold of Bactria shook the world of archaeology," he writes in the exhibition catalog. "Nowhere in antiquity have so many different objects from so many different cultures—Chinese-inspired boot buckles, Roman coins, daggers in a Siberian style—been found together in situ."

Sarianidi first came to the Bactrian plain in 1969 to search for traces of the Silk Road. After excavating ruins of a first-century a.d. city there, he stumbled across, and soon began uncovering, an Iron Age temple used for fire worship that dated from 1500 to 1300 b.c. While carting away earth from the temple mound in November 1978, a worker spied a small gold disk in the ground. After inspecting it, Sarianidi dug deeper, slowly revealing a skull and skeleton surrounded by gold jewelry and ornaments—the remains of a woman, 25 to 30 years old, whom he called a nomadic princess. He subsequently found and excavated five additional graves, all simple trenches containing lidless wooden coffins holding the remains of once ornately attired bodies. Over the next three months, he cleaned and inventoried more than 20,000 individual items, including hundreds of gold spangles, each about the size of a fingernail.

In the grave of a chieftain—the only male found at the site—Sarianidi's team uncovered turquoise-studded daggers and sheaths and a braided gold belt with raised medallions that bear the image, some say, of Dionysus, the Greek god of wine, riding sidesaddle on a panther. (Others speculate it's the Bactrian goddess Nana seated on a lion.) Near the chieftain's rib cage, excavators found an Indian medallion that, according to Véronique Schiltz, a French archaeologist with the National Center for Scientific Research in Paris, bears one of the earliest representations of Buddha. The man had been buried with his head resting on a gold plate on a silk cushion. Around him lay two bows, a long sword, a leather folding stool and the skull and bones of a horse.

In a nearby grave, the archaeological team found the remains of a woman in her 30s wearing signet rings with images of Athena, the Greek goddess of wisdom, and a pair of matching jeweled pendants with gold figures grasping S-shaped dragons, as if to tame them. Another grave, that of a teenage girl, contained thin gold shoe soles (meant, says Hiebert, for the afterlife), along with a Roman coin minted in the early first century a.d. in Gallic Lugdunum (present-day Lyon, France). Schiltz says the coin probably came to southern India by sea before ending up with the woman through trade or as booty.

Schiltz also speculates that the nomads had migrated south from Central Asia or China and ended up plundering the Greco-Bactrian cities. The opulent jewelry that accompanied their burials, she says, indicates that the group belonged to a ruling family. The graves apparently survived intact because they were well concealed in the ruins of the Iron Age temple.

Archaeological evidence about nomadic groups is rare, for obvious reasons. The Tillya Tepe graves contained the first examples of nomadic art to be found in Afghanistan. Initially Hiebert thought the nomads had acquired the artifacts by "cherry-picking the Silk Road," he says. But after inventorying the objects, he was persuaded by their similarities that they all came from a single local workshop.

"That meant that these nomads took iconography from Greece, Rome, China, India, even as far away as Siberia, and put it together into their own unique and highly refined art style," he says. "They were creators, not merely collectors." He suspects that the workshop lies buried near the tombs.

In late 1978, just before the outbreak of widespread civil war in Afghanistan, armed tribesmen began threatening the dig. By February 1979, the political situation and the impending onset of winter caused Sarianidi to abandon the site before he could excavate a seventh grave; it would later be stripped by looters. Sarianidi crated up the artifacts he had found at the site and brought them to the National Museum in Kabul, where they remained until their removal to the bank vault in 1989.

Golden Bowls

The oldest pieces in the National Gallery exhibition, which date from 2200 to 1900 b.c., were found in Tepe Fullol, also in northern Afghanistan, in July 1966, when farmers there accidentally plowed up a Bronze Age grave, then began divvying up the priceless artifacts with an ax. Local authorities managed to salvage a dozen gold and silver cups and bowls (along with some gold and silver fragments), which they turned over to the National Museum. Jean-François Jarrige, director of Paris' Guimet Museum and a Bronze Age specialist, says that the bowls are connected to the craftsmanship of what is known as the Bronze Age Oxus culture, which existed within a large geographic area in Central Asia encompassing what is now Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan and Afghanistan. The geometric "stepped-square" motifs on one goblet, for instance, resemble designs uncovered in Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan, and the gold itself likely came from Central Asia's Amu Darya River (known in antiquity as the Oxus). But although these bowls have something of a local character, says Jarrige, "they also show signs of outside influences...in particular the representation of bearded bulls reminiscent of a generally recognized theme from Mesopotamia." The designs on these bowls, write the curators, "include animal imagery from distant Mesopotamian and Indus Valley (present-day Pakistan) cultures, indicating that already at this early date, Afghanistan was part of an extensive trade network."

Greeks Bearing Gifts

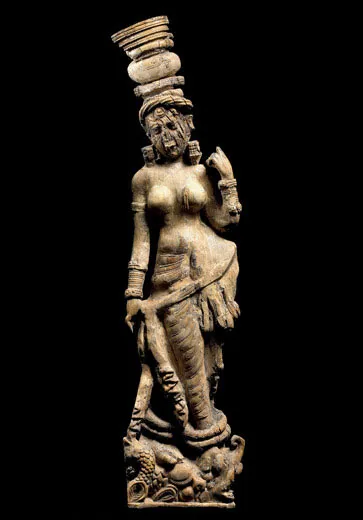

One of the most important ancient cities in Afghanistan was discovered in 1964 at Ai Khanum, also in the northern region formerly known as Bactria. Founded around 300 b.c. by Seleucus I, a Macedonian general who won a power struggle to control the region following the death of Alexander the Great in 323 b.c., the city became the eastern outpost of Greek culture in Asia. Its artifacts reflect Greek and Indian, as well as local, artistic traditions. Works featured in the exhibition include a seven-inch-high bronze figure of Hercules and a gilded silver plaque that combines Greek and Persian elements. It depicts Cybele, the Greek goddess of nature, riding in a Persian-style chariot, shaded by a large parasol held by a priest.

Like Tillya Tepe and Tepe Fullol, Ai Khanum was also discovered by chance. While out hunting game in 1961 near the border with the then Soviet Tajik Republic (present-day Tajikistan), the last Afghan king, Zahir Shah, was presented with a carved chunk of limestone by local villagers. The king later showed the fragment to Daniel Schlumberger—then the director of a French archaeological expedition in Afghanistan—who recognized it as coming from a Corinthian, likely Greek, capital. (A similar capital is displayed in the show.) In November 1964, Schlumberger led a team to Ai Khanum, where, after digging up shards bearing Greek letters, he began excavations that continued until the Soviet invasion in December 1979.

Shaped like a triangle, roughly a mile on each side, the city, which was strategically located at the junction of the Oxus and Kokcha rivers, was dominated by an acropolis situated on a flat-topped, 200-foot-high bluff. Its huge entry courtyard was surrounded by airy colonnades supported by 126 Corinthian columns. Beyond the courtyard lay reception halls, ceremonial rooms, private residences, a treasury, a large bathhouse, a temple and a theater.

As in nearly every Greek city, there was a gymnasium, or school, and in it excavators found two sundials that appear to have been used to teach astronomy. Unusually, one of them was calibrated for the Indian astronomical center of Ujjain, at a latitude some 14 degrees south of Ai Khanum—an indication, says Paul Bernard, a member of the French excavation team, of scholarly exchanges among Greek and Indian astronomers.

Based on Indian works discovered at the site, Bernard believes that in the second century b.c., Ai Khanum became the Greco-Bactrian capital city Eucratidia, named for the expansionist king Eucratides, who likely brought the pieces back from India as spoils from his military campaigns there. After a century and a half as an outpost of Hellenistic culture in Afghanistan, the city came to a violent end. Eucratides was murdered in 145 b.c., apparently touching off a civil conflict that left the city vulnerable to marauding nomads, who burned and destroyed it the same year. Sadly, the archaeological site of Ai Khanum met a similar fate; it was looted and nearly obliterated during the years of Soviet occupation and civil strife in Afghanistan.

A Fortress in the Hindu Kush

In 329 b.c., Alexander the Great is believed to have established the fortress city of Alexandria of the Caucasus in a lush river valley south of the Hindu Kush mountains about 50 miles north of Kabul. Now known as Begram, the city was an important trading center for the Greco-Bactrian kingdom from about 250 to 100 b.c. and continued to thrive under the Kushan Empire that arose in the first century a.d.

According to Sanjyot Mehendale, a Near Eastern authority at the University of California at Berkeley, the Roman glass and bronze, Chinese lacquer and hundreds of Indian-style ivory plaques and sculptures unearthed at Begram in 1937 and 1939 suggested that the city had been a major commodities juncture along the Silk Road. Although French archaeologists Joseph and Ria Hackin, who excavated the site, concluded that Begram was the summer residence of the Kushan emperors, Mehendale believes that two sealed rooms containing what the Hackins called "royal treasure" were actually a merchant's shop or warehouse.

The glassware and bronze, she says, likely arrived by sea from Roman Egypt and Syria to ports near present-day Karachi, Pakistan, and Gujarat in western India, and were then transported overland by camel caravan. The exhibition's Begram section includes plaster medallions depicting Greek myths; ivory plaques recounting events from the life of Buddha; and whimsical fish-shaped flasks of blown colored glass.

In retrospect, National Museum of Afghanistan director Omara Khan Masoudi's decision to hide the Bactrian Hoard and other archaeological treasures in 1989 seems fortuitously prescient. Once an impressive cultural repository, the Kabul museum suffered massive damage and extensive looting during the factional conflicts of the 1990s. Then, in March 2001, the Taliban rampaged through the museum, smashing sculptures of the human form it viewed as heretical, destroying more than 2,000 artifacts. Although the National Museum was recently rebuilt with foreign assistance, it is not safe enough to display the country's most valuable treasures. The museum has received funds from the current exhibition tour, and there is a proposal to build a new, more secure museum closer to the center of Kabul, but it will be years before such a project can even be started. During the past year, about 7,000 visitors came to the museum; the numbers seem to matter less than the symbolic importance of keeping the building open. "The war destroyed so much," says Masoudi, "so whatever we can do to show off our ancient civilization—here and abroad—makes us proud."

Masoudi and Said Tayeb Jawad, Afghanistan's ambassador to the United States, believe the current exhibition represents a cultural reawakening and, perhaps, even a turning point. "We hope this exhibit will help overcome the darkness of Afghanistan's recent history," says Jawad, "and shed some light on its rich past, thousands of years old, as a crossroads of cultures and civilizations."

Author Richard Covington lives outside Paris and writes frequently on art, culture, the environment and social issues.