Making Beautiful Art out of Beach Plastic

Artists Judith and Richard Lang comb the California beaches, looking for trash for their captivating, yet unsettling work

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/beach-plastic-arrangement-631.jpg)

Judith Lang waves from a kelp pile on Kehoe Beach, shouting to her husband. “Here’s the Pick of the Day!”

The artist holds aloft her newfound treasure: the six-inch long, black plastic leg of an anonymous superhero toy. But did it come from Batman or Darth Vader? Only careful research will tell.

“We’ll google ‘black plastic doll leg,’” Richard Lang informs me, “and try to find out what it belonged to.”

In 1999, Richard and Judith had their first date on this Northern California beach. Both were already accomplished artists who had taught watercolor classes at the University of California and shown their work in San Francisco galleries. And both (unbeknown to each other) had been collecting beach plastic for years.

“This is a love story,” Richard says quietly. “Our passion is not only plastic but each other. We could never have imagined, on that day, what an incredible life would unfold—picking up other people’s garbage.”

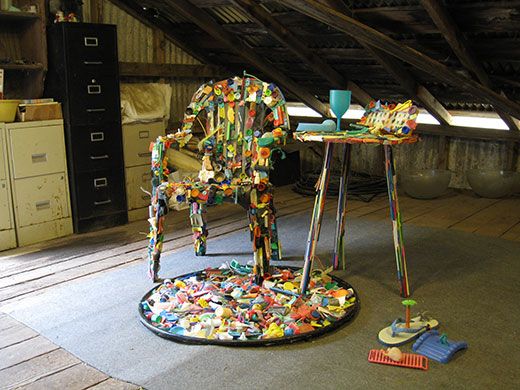

It’s not just about picking up the plastic, but what he and Judith do with it. Since 1999, they’ve found countless ways to turn their huge collection of beach debris into extraordinary art. Partners and collaborators, they have created found-object works ranging from exquisite jewelry to mural-size photographs; from wall-mounted sculptures to, most recently, the coveted trophies awarded at the 2011 Telluride Mountainfilm Festival. Their work has appeared in exhibitions worldwide, from Singapore to San Francisco’s Museum of Modern Art.

“Our hope is to make these artworks so valuable,” Judith jokes, “that wars will be fought to clean up these beaches.”

* * *

A curving expanse of sand, kelp and driftwood patrolled by peregrine falcons, Kehoe rests on the edge of the Point Reyes National Seashore. It’s also on the edge of the North Pacific Gyre—a slow-moving ocean vortex that carries trash in an immense circuit around the sea.

The stormy season between December and April is the best time to search the beach for washed-up plastic. “It comes from cruise ship dumping, trash in the gutter, picnickers, tsunamis, hunters, farmers…” Richard says, shaking his head. “It reminds us that there is no away in ‘throwaway’ culture.”

Since 1999, the Langs have collected more than two tons of plastic. But it’s not your typical beach cleanup. “We’re not cleaning,” Richard points out. “We’re curating.”

During our two hours on Kehoe, we find plenty of common items: white Tiparillo tips, old Bic lighters, shriveled balloons, corroded SuperBalls, nylon rope and shotgun wads: the frayed plastic cores of shotgun shells, expelled when a shot is fired. The Langs scour the tide line and search below the rocky cliffs with Zen-like concentration. In the past, diligence has rewarded them with everything from vintage toy soldiers to tiny red Monopoly houses. But finding plastic on the beach, even if it’s your main art material, is always bittersweet. Vastly outnumbering those rare treasures are single-use water bottles, sun lotion tubes, soft-drink lids—and tiny round pellets called nurdles.

Nurdles, or “mermaid’s tears,” are by far the most common plastic found on Kehoe, in fact on any beach along the North Pacific Gyre. Smaller than popcorn kernels, these are the raw material from which plastic objects are made. Millions of nurdles escape during the manufacturing and transportation process, and often wash out to sea. The chemically receptive pellets readily absorb organic pollutants, and toxins like DDT and PCBs.

“They look like fish eggs,” observes Judith, holding one on her fingertip. “So birds eat them, and fish eat them. They’re little toxic time bombs, working their way up the food chain.”

Richard approaches, his high spirits temporarily grounded. “We put a gloss on what we do and joke that it’s ‘garbage yoga’,” he says, “because there’s so much bending down and physical activity involved…”

“But it’s pretty sad,” continues Judith, finishing his thought. “To see this plastic strewn all over the beach. And it’s so recent. I remember going to the beach as a child; I never saw plastic. This problem has washed into our lives—and it’s not going to wash out any time soon.”

But creating beauty out of an ugly phenomenon—while raising awareness about the plague of plastic trash inundating the world’s oceans and beaches—is the Lang’s primary mission.

“When we make artwork out of this garbage, people are surprised,” says Judith. “They almost feel that it’s horrible these things are so beautiful.”

* * *

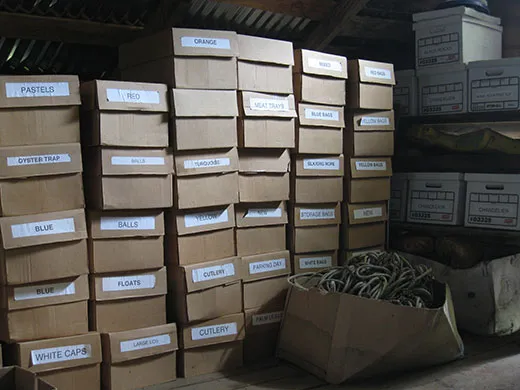

The Langs drive back home from Kehoe Beach with bulging duffle bags. The day’s harvest is rinsed off in a big bucket, laid out to dry and sorted by color, shape or purpose. Each piece of plastic they find has a secret story: a girl’s pink barrette; a kazoo; a tiny Pinocchio weathered almost beyond recognition.

Dozens of banker’s boxes are stacked in the artists’ studio (and in a rustic barn along the driveway of their home). Their sides are labeled by color or category: Red; Shoes; Yellow; Cutlery; Large Lids; Turquoise.

“And here’s a new category,” says Judith, holding up an unrecognizable chunk. “Plastic That Has Been Chewed On.”

The Langs often assemble sculptures from their beach plastic. Judith, working independently, fashions exquisite jewelry from some rather audacious objects. “I just sold a beautiful necklace made of white, pink and blue tampon applicators to Yale University,” she says merrily. “Along with a shotgun wad necklace. I’m hoping they’ll display the two together—and call it Shotgun Wedding.”

Most of their current work, though, involves large-scale photography of the beach plastic arranged in evocative groups. Their palette of objects is spread over a wide table covered with butcher’s paper. Surveying the objects, I spy paint can spray heads, doll arms, picture frames, a flamingo head, plastic fruit, rubber cement brushes, a toy horse, bits of plastic spaceships, dental floss picks, umbrella handles, cat toys, cheese spreaders, chunks of AstroTurf and squirt gun plugs.

“One of us will put a few pieces together,” Judith says, placing a few blue and green objects in a kind of arc. “That’s a beginning.”

“It kind of drifts around,” explains Richard, adding a pink hair curler. “Imagine the pieces as larval plankton, bumping against a newly formed volcanic rock.”

The artworks accrete slowly, like coral atolls. Arguments and epiphanies ensue. When the Langs are satisfied with their creation, they transport the objects to the Electric Works, Richard’s photography studio and art gallery in San Francisco’s Soma district. There, using a large-format digital camera, they capture their assemblage down to the finest detail.

Visually captivating and ecologically unsettling, the Langs’ pollutant-based artworks inspire a wry ambivalence. Beautiful as they are, I can’t help but wish they didn’t exist. But despite the “message” inherent in their work, Richard and Judith don’t treat it as a political statement.

“We’re artists first,” says Richard. “What we care about is creating beauty.”

By way of illustration, the Langs show me a striking photograph of luminescent domes glowing against a dark, textured background. After a moment, I recognize the dome-like objects: they’re highly magnified nurdles.

“We feel that beauty is a much better way to covey our message,” says Judith. “To be presented by these mysterious, glowing orbs creates intrigue. Then we can say, ‘We’re glad that you’re interested. Now let's talk about what this really is.’ ”