Monsters reveal more about humans than one might think. As figments of the imagination, the alien, creepy-crawly, fanged, winged and otherwise-terrifying creatures that populate myths have long helped societies define cultural boundaries and answer an age-old question: What counts as human, and what counts as monstrous?

In the classical Greek and Roman myths that pervade Western lore today, a perhaps surprising number of these creatures are coded as women. These villains, wrote classicist Debbie Felton in a 2013 essay, “all spoke to men’s fear of women’s destructive potential. The myths then, to a certain extent, fulfill a male fantasy of conquering and controlling the female.”

Ancient male authors inscribed their fear of—and desire for—women into tales about monstrous females: In his first-century A.D. epic Metamorphoses, for example, the Roman poet Ovid wrote about Medusa, a terrifying Gorgon whose serpentine tresses turned anyone who met her gaze into stone. Earlier, in Homer’s Odyssey, composed around the seventh or eighth century B.C., the Greek hero Odysseus must choose between fighting Scylla, a six-headed, twelve-legged barking creature, and Charybdis, a sea monster of doom. Both are described as unambiguously female.

These stories may sound fantastical today, but for ancient people, they reflected a “quasi-historical” reality, a lost past in which humans lived alongside heroes, gods and the supernatural, as curator Madeleine Glennon wrote for the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2017. What’s more, the tales’ female monsters reveal more about the patriarchal constraints placed on womanhood than they do about women themselves. Medusa struck fear into ancient hearts because she was both deceptively beautiful and hideously ugly; Charybdis terrified Odysseus and his men because she represented a churning pit of bottomless hunger.

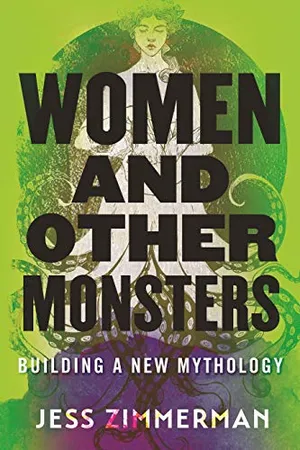

Female monsters represent “the bedtime stories patriarchy tells itself,” reinforcing expectations about women’s bodies and behavior, argues journalist and critic Jess Zimmerman in Women and Other Monsters: Building a New Mythology. In this essay collection, newly published by Beacon Press, she reexamines the monsters of antiquity through a feminist lens. “Women have been monsters, and monsters have been women, in centuries’ worth of stories,” she notes in the book, “because stories are a way to encode these expectations and pass them on.”

Women and Other Monsters: Building a New Mythology

A fresh cultural analysis of female monsters from Greek mythology

A mythology enthusiast raised on D’Aulaires Book of Greek Myths, Zimmerman writes personal essays that blend literary analysis with memoir to consider each monster as an extended metaphor for the expectations placed on women in the present moment. She relies on the translations and research of other classics scholars, including “monster theory” expert Jeffrey Jerome Cohen, Debbie Felton on monstrosity in the ancient world, Kiki Karoglou's analysis of Medusa, Robert E. Bell’s Women of Classic Mythology and Marianne Hopman on Scylla.

Zimmerman also joins the ranks of other contemporary writers who have creatively reimagined the significance of these monstrous women—for instance, Muriel Rukeyser, who wrote poetry about the Sphinx; Margaret Atwood, who retold the story of Odysseus’ wife, Penelope; and Madeline Miller, who penned a 2018 novel about the Greek enchantress Circe.

Though fearsome female monsters pop up in cultural traditions worldwide, Zimmerman chose to focus on ancient Greek and Roman antiquity, which have been impressed on American culture for generations. “Greek mythology [had] a heavy, heavy influence on Renaissance literature, and art and Renaissance literature [have] a heavy influence on our ideas now, about what constitutes literary quality, from a very white, cis[gendered], male perspective,” she explains in an interview.

Below, explore how the myths behind six “terrible” monsters, from the all-knowing Sphinx to the fire-breathing Chimera and the lesser-known shapeshifter Lamia, can illuminate issues in modern-day feminism. Zimmerman’s book takes a wide view of these stories and their history, linking the ancient past to modern politics. She says, “My hope is that when you do go back to the original texts to read these stories, you can think about, ‘What is this story trying to pass on to me?’”

She also argues that the qualities that marked these female creatures as “monstrous” to ancient eyes might have actually been their greatest strengths. What if, instead of fearing these ancient monsters, contemporary readers embraced them as heroes in their own right? “The traits the [monsters] represent—aspiration, knowledge, strength, desire—are not hideous,” Zimmerman writes. “In men’s hands, they have always been heroic.”

Scylla and Charybdis

As Homer’s Odysseus and his men attempt to sail back home to Ithaca, they must pass through a narrow, perilous channel fraught with danger on both sides. Scylla—a six-headed, twelve-legged creature with necks that extend to horrible lengths and wolf-like heads that snatch and eat unsuspecting sailors—resides in a clifftop cave. On the other side of the strait, the ocean monster Charybdis rages and threatens to drown the entire ship.

This pair of monsters, Scylla and Charybdis, interested Zimmerman because “they’re represented as things that Odysseus just has to get past,” she says. “So they become part of his heroic story. But surely that’s not their only purpose? Or at least, it doesn’t have to be their only purpose.”

Homer described Scylla as a monster with few human characteristics. But in Ovid’s retelling, written about 700 years later, Circe, in a jealous fit of rage, turns Scylla’s legs into a writhing mass of barking dogs. As Zimmerman points out in Women and Other Monsters, what makes Scylla horrifying in this version of the story is “the contrast between her beautiful face and her monstrous nethers”—a metaphor, she argues, for the disgust and fear with which male-dominated societies regard women’s bodies when they behave in unruly ways.

As for Charybdis, the second-century B.C. Greek historian Polybius first suggested that the monster might have corresponded to a geographic reality—a whirlpool that threatened actual sailors along the Strait of Messina. In the Odyssey, the Greek hero barely escapes her clutches by clinging to the splintered remains of his ship.

“[V]oraciousness is [Charybdis’] weapon and her gift,” Zimmerman writes, proposing a new dynamic of the story. “What strength the unapologetically hungry monster-heroine could have: enough to swallow a man.”

Lamia

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6b/54/6b546b57-87ce-4876-a7df-39fe5b64e349/lamia_waterhouse.jpeg)

Lamia, one of the lesser-known demons of classical mythology, is a bit of a shapeshifter. She appears in Greek playwright Aristophanes’ fifth-century B.C. comedy Peace, then all but vanishes before reemerging in 17th- and 18th- century European literature, most notably the Romantic poetry of John Keats.

Some stories hold that Lamia has the upper body of a woman but the lower half of a snake; her name in ancient Greek translates roughly to “rogue shark.” Other tales represent her as a woman with paws, scales and male genitalia, or even as a swarm of multiple vampiric monsters. Regardless of which account one reads, Lamia’s primary vice remains the same: She steals and eats children.

Lamia is motivated by grief; her children, fathered by Zeus, are killed by Hera, Zeus’ wife, in yet another mythological pique of rage. In her sorrow, Lamia plucks out her own eyes and wanders in search of others’ children; in some retellings, Zeus gives her the ability to take out her own eyes and put them back at will. (Like Lamia’s origin story, the reasons for this gift vary from one story to the other. One plausible explanation, according to Zimmerman, is that Zeus offers this as a small act of mercy toward Lamia, who is unable to stop envisioning her dead children.)

Zimmerman posits that Lamia represents a deep-seated fear about the threats women pose to children in their societally prescribed roles as primary caregivers. As Felton wrote in 2013, “That women could also sometimes produce children with physical abnormalities only added to the perception of women as potentially terrifying and destructive.”

Women are expected to care for children, but society remains “constantly worried [they] are going to fail in their obligation to be mothers and to be nurturers,” Zimmerman says. If a woman rejects motherhood, expresses ambivalence about motherhood, loves her child too much or loves them too little, all of these acts are perceived as violations, albeit to varying degrees.

“To deviate in any way from the prescribed motherhood narrative is to be made a monster, a destroyer of children,” Zimmerman writes.

And this fear wasn’t limited to Greek stories: La Llorona in Latin America, Penanggalan in Malaysia and Lamashtu in Mesopotamia all stole children as well.

Medusa

Like most mythical monsters, Medusa meets her end at the hands of a male hero. Perseus manages to kill her, but only with the aid of a slew of overpowered tools: winged sandals from messenger god Hermes; a cap of invisibility from the god of the underworld, Hades; and a mirror-like shield from the goddess of wisdom and war, Athena.

He needed all the reinforcement he could muster. As one of the Gorgons, a trio of winged women with venomous snakes for hair, Medusa ranked among the most feared, powerful monsters to dominate early Greek mythology. In some versions of their origin story, the sisters descended from Gaia, the personification of Earth herself. Anyone who looked them in the face would turn to stone.

Of the three, Medusa was the only mortal Gorgon. In Ovid’s telling, she was once a beautiful maiden. But after Poseidon, the god of the sea, raped her in the temple of Athena, the goddess sought revenge for what she viewed as an act of defilement. Rather than punishing Poseidon, Athena transformed his victim, Medusa, into a hideous monster.

Interestingly, artistic depictions of Medusa changed dramatically over time, becoming increasingly gendered, said Karaglou, curator of the Met exhibition “Dangerous Beauty: Medusa in Classical Art,” in a 2018 interview. In the show, Karaglou united more than 60 depictions of Medusa’s face. Sculptures of the monster from the archaic Greek period, roughly 700 to 480 B.C., are mostly androgynous figures. Designed to be ugly and threatening, they boast beards, tusks and grimaces.

Fast forward to later centuries, and statues of Medusa become much more recognizably beautiful. “Beauty, like monstrosity, enthralls, and female beauty in particular was perceived—and, to a certain extent, is still perceived—to be both enchanting and dangerous, or even fatal,” wrote Karaglou in a 2018 essay. As the centuries progressed, Medusa’s duplicitous beauty became synonymous with the danger she posed, cementing the trope of a villainous seductress that endures to this day.

Chimera

Chimera, referenced in Hesiod’s seventh-century B.C. Theogony and featured in Homer’s the Iliad, was a monstrous jumble of disparate parts: a lion in front, a goat in the middle, and a dragon or snake on the end. She breathed fire, flew and ravaged helpless towns. In particular, she terrorized Lycia, an ancient maritime district in what is now southwest Turkey, until the hero Bellerophon managed to lodge a lead-tipped spear in her throat and choke her to death.

Of all the fictional monsters, Chimera may have had the strongest roots in reality. Several later historians, including Pliny the Elder, argue that her story is an example of a “euhemerism,” when ancient myth might have corresponded to historical fact. In Chimera’s case, the people of Lycia may have been inspired by nearby geological activity at Mount Chimera, a geothermally active area where methane gas ignites and seeps through cracks in the rocks, creating little bursts of flames.

“You can go take a hike there today, and people boil their tea on top of these little spurts of geological activity,” Zimmerman says.

For ancient Greeks who told stories about the monster, Chimera’s particular union of dangerous beasts and the domestic goat represented a hybrid, contradictory horror that mirrored the way women were perceived as both symbols of domesticity and potential threats. On one hand, writes Zimmerman, Chimera’s goat body “carries all the burdens of the home, protects babies … and feeds them from her body.” On the other, her monstrous elements “roar and cry and breathe fire.”

She adds, “What [the goat] adds is not new strength, but another kind of fearsomeness: the fear of the irreducible, of the unpredictable.”

Chimera’s legend proved so influential that it even seeped into modern language: In scientific communities, “chimera” now refers to any creature with two sets of DNA. More generally, the term refers to a fantastical figment of someone’s imagination.

The Sphinx

One of the most recognizable giants of antiquity, the Sphinx was a figure popular across Egypt, Asia and Greece. A hybrid of various creatures, the mythical being assumed different meanings in each of these cultures. In ancient Egypt, for instance, the 66-foot-tall lion-bodied statue that guards the Great Pyramid of Giza was likely male and designed, accordingly, as a male symbol of power.

Across the Mediterranean, playwright Sophocles wrote the Sphinx into his fifth-century B.C. tragedy Oedipus Rex as a female monster with the body of a cat, the wings of a bird, and a foreboding reservoir of wisdom and riddles. She travels to Thebes from foreign lands and devours anyone who cannot correctly answer her riddle: What goes on four legs in the morning, two feet at noon and three in the evening? (Answer: a man, who crawls as a baby, walks as an adult and uses a cane as an elder.)

When Oedipus successfully completes her puzzle, the Sphinx is so distraught that she throws herself to her death. This, Zimmerman writes, is the logical conclusion for a culture that punished women for keeping knowledge to themselves. Knowledge is power—that’s why in modern history, Zimmerman argues, men have excluded women from access to formal education.

“The story of the Sphinx is the story of a woman with questions men can’t answer,” she writes. “Men didn’t take that any better in the fifth century [B.C.] than they do now.”

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

:focal(282x171:283x172)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d0/b1/d0b150e5-ca51-4300-a0fc-c940f1999027/myth_mobile.jpg)

:focal(1047x323:1048x324)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/0c/2e/0c2ebd25-317c-4da8-8caa-82035e73c73b/myth.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)