Music That Rocks the Imagination

The motivation behind Quetzal’s music is stirring dreams – and helping build communities

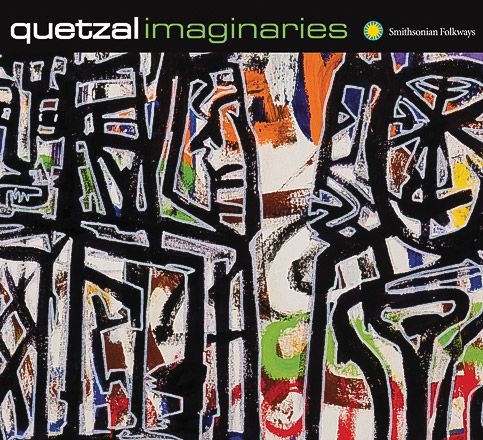

The socially conscious California rock band Quetzal was formed in 1992 and its musicians draw from a wide range of influences—from the Chicano rock of their native East Los Angeles to the traditional son jarocho of Veracruz, Mexico. Called “a world class act” by the Los Angeles Times, the group has a new album, Imaginaries, from Smithsonian Folkways Recordings, a lively mix of the traditional, salsa, rhythm and blues, and international pop music. “Dreamers, Schemers,” a track from Imaginaries, celebrates Latin freestyle of the 1980s, in which musicians, DJs and partygoers bonded over the music. The magazine’s Aviva Shen spoke with the group’s founder, Quetzal Flores.

How do these songs relate to each other? Do they come from different energies or are they the same?

It comes down to a need to belong. A basic human need is to belong either to a family or to a community. And so often the way that we live is contrary to that. If you close your doors, you don’t know who your neighbors are. When there’s no communication, there’s no contact. Everyone’s living in fear. I think when people go out and convene, or when people go out and take situations into their own hands, it is healthy, it is cathartic. Again, it creates that imaginary space because all of a sudden you feel different, or you’re able to see something different and the possibilities are endless.

Tell me about the song “Dreamers, Schemers.”

“Dreamers, Schemers” is about this moment in the 1980s, in Los Angeles, where young kids—high school kids—organized themselves into a network of promoters, social clubs, DJs and partygoers. The majority of it took place in backyards. It included a way of dressing—a style of dressing, a style of combing your hair. I would even go so far as to say it was related to what the Pachucos of the 1930s and ’40s used to do. The Pachucos had their culture, their dress, their way of talking, the music they listened to, they danced to, the spaces for them to convene, which is very important. I think the most important part of the 1980s movement was the idea of convening, and being together in a space. Most of the time it was in a safe environment, where you knew you were going to see friends and other people from different neighborhoods and different places. But for the most part it was a community-building effort.

The Fandango traditions of Veracruz, incorporate music, song and dance to generate a spirit of community. For the past decade, you have build a combined movement with musicians in Veracruz and California called Fandango Sin Fronteras or Fandango Without Borders. Is this a similar community-building “moment” to the one you’ve described in “Dreamers, Schemers”?

Today in Los Angeles, the Fandango is another example of that, another level of that. I grew up with progressive parents and I inherited from them a desire to organize and build community. When a group of us started building these relationships with the community in Veracruz, the Fandango was one of the most attractive elements of that. It involved the same sort of idea of convening—being in community with music, being in music with community.

What is Imaginaries about? And how does this relate to a culture of convening, or community?

The “imaginaries” are the spaces people in struggle create in order to feel human, to dream, to imagine another world. Cultures of convening around music or other things, they become vehicles, mechanisms, tools by which you’re able to navigate outside of the system. It’s called outward mobility. It is moving out of the way of a falling structure in transit to the imaginary. You find these spaces or vehicles everywhere right now; they’re starting to pop up everywhere. It’s going to be the saving grace of people who struggle. Another important part of these spaces is that while you transit and mobilize outside of the system, you’re able to build parallel structures that are much smaller, sustainable, local and interconnected.

Do you feel like your background growing up in East L.A. helps you speak about this idea in a certain way?

I don’t know if it’s necessarily East L.A., but it’s definitely growing up with progressive parents. That background had everything to do with it. Everyone around me, all the people my parents were hanging out with, were people who were constantly thinking about this: How do we make things better for everybody, not just for ourselves?

So it goes along with that idea of convening, and having a community dialogue.

Again, I honestly feel there’s no greater intelligence than the intelligence of a community. For example, my mother worked in the projects here in L.A. They were having the problem of all these young elementary school kids getting jumped by gangs on the way home from school. Their purpose was to get the kids to sell drugs, because if they get caught selling drugs, the offense is not as great. The moms got together and organized. They said here’s what we’re going to do. We’re going to stand on every street corner with walkie-talkies and green shirts. We’re going to stand right next to the drug dealers. And we’re going to make life very uncomfortable for them and take this situation into our own hands. The cops are useless. There’s no infrastructure to deal with this situation. There was no judging going on. It was just a situation that they had to deal with. It was called “Safe Passage.” They were getting death threats, but they stayed. They did not let them scare them away. And sure enough, the folks who were selling drugs eventually left. So how intelligent is that? Those kinds of people are heroes to me.

What kind of message do you want people to take away from this album?

I’m hoping people will take away a message of imagination and of dreaming. Of dreaming for each other, and dreaming for the purpose of connecting to one another. And also, I hope that some people get upset about it. I hope people react to it. Unless there’s conversation, unless there’s reaction to it, then we’re not doing our job.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/ATM-aviva-shen-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/ATM-aviva-shen-240.jpg)