Never Underestimate the Power of a Paint Tube

Without this simple invention, impressionists such as Claude Monet wouldn’t have been able to create their works of genius

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Phenomenon-color-app-tin-tube-631.jpg)

The French Impressionists disdained laborious academic sketches and tastefully muted paintings in favor of stunning colors and textures that conveyed the immediacy of life pulsating around them. Yet the breakthroughs of Monet, Pissarro, Renoir and others would not have been possible if it hadn’t been for an ingenious but little-known American portrait painter, John G. Rand.

Like many artists, Rand, a Charleston native living in London in 1841, struggled to keep his oil paints from drying out before he could use them. At the time, the best paint storage was a pig’s bladder sealed with string; an artist would prick the bladder with a tack to get at the paint. But there was no way to completely plug the hole afterward. And bladders didn’t travel well, frequently bursting open.

Rand’s brush with greatness came in the form of a revolutionary invention: the paint tube. Made from tin and sealed with a screw cap, Rand’s collapsible tube gave paint a long shelf life, didn’t leak and could be repeatedly opened and closed.

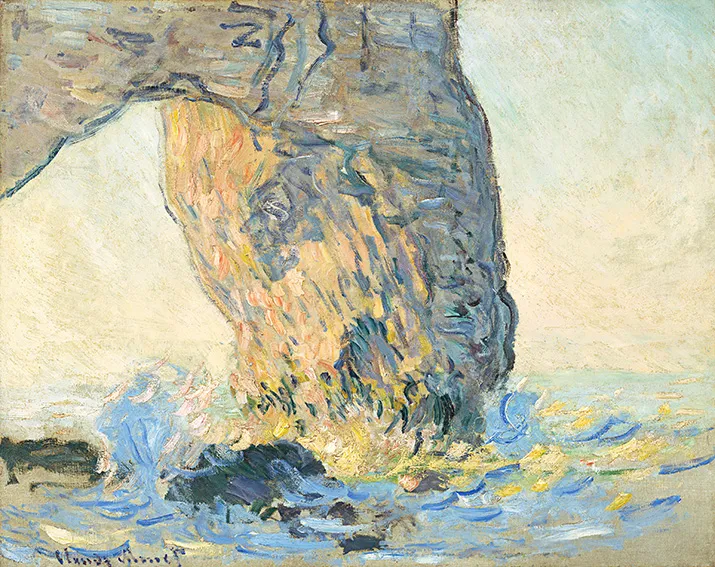

The eminently portable paint tube was slow to be accepted by many French artists (it added considerably to the price of paint), but when it caught on it was exactly what the Impressionists needed to abet their escape from the confines of the studio, to take their inspiration directly from the world around them and commit it to canvas, particularly the effect of natural light. For the first time in history, it was practical to produce a finished oil painting on-site, whether in a garden, a café or in the countryside (although art critics would long argue if Impressionist paintings were truly “finished”). For his 1885 canvas Waves at the Manneporte (pictured at left)—bursting with red, blue, violet, yellow and green—Claude Monet had to walk along several beaches and through a long dark tunnel in a cliff side to reach the Manneporte, an extraordinary rock outcrop on the rough northern coast of France. On one occasion, he and his easel were nearly swept off the beach into the sea. Waves at the Manneporte appears to have been created on the spot in two or three sessions. (Sand from the beach can be found embedded in the paint.)

Rand’s tubes carried inside them another crucial element as well: new colors. Paint pigments had remained nearly unchanged since the Renaissance. Since oil paints were time-consuming to produce and quick to dry out, artists prepared only a few colors to work with during a painting session and would fill in just one area of a canvas at a time (such as a blue sky or red dress). But Rand’s tin tubes enabled the Impressionists to take full advantage of dazzling new pigments—such as chrome yellow and emerald green—that had been invented by industrial chemists in the 19th century. With the full rainbow of colors from tubes on their palettes, the Impressionists could record a fleeting moment in its entirety. “Don’t paint bit by bit,” Camille Pissarro advised, “but paint everything at once by placing tones everywhere.”

Pierre-Auguste Renoir said, “Without colors in tubes, there would be no Cézanne, no Monet, no Pissarro, and no Impressionism.” Some revolutions began with the squeeze of a trigger; others required just the squeeze.