New York City’s Disappearing Mom-and-Pop Storefronts

Two photographers set out to see what happened to small family businesses in New York City in a decade

In cities, change doesn't always come with the sounds of bulldozers and wrecking balls. Sometimes, something as seemingly small as moving sausages down from a window can be a sign of changing tides.

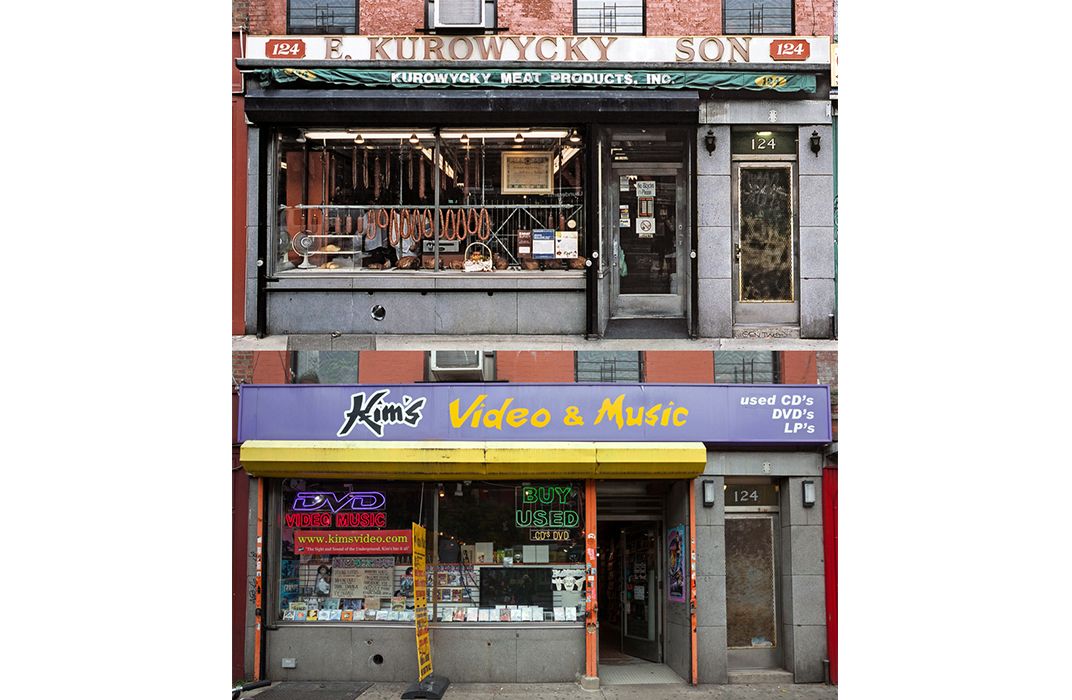

In the early 2000s, photographers James and Karla Murray began a project to capture New York City's iconic storefronts—the city's unique, mom-and-pop restaurants, shops and bars—before they disappeared. One shop that caught their eye belonged to Jerry Kurowycky, a third-generation owner of E. Kurowycky & Sons Meat Market on First Avenue in the East Village, a Ukrainian butcher shop that catered to the neighborhood's once bustling Ukrainian population. The photographers struck up a conversation with Kurowycky, which they chronicled in their book Store Front - The Disappearing Face of New York. Kurowycky spoke proudly of his shop's adherence to old traditions, boasting that they made all their wares by hand, the old-fashioned way—the way his grandfather made it in Eastern Europe before WWII.

"Nothing has changed," he told the photographers. "We use the same family recipes. We are allowed to smoke meats on premises because we are grandfathered in as far as our smoker is concerned since it’s been in operation since the 1920s."

Four years later, James and Karla returned to the shop—and things had changed. Kurowycky's sausages no longer hung in the window fronts to entice sidewalk customers. The smoked ham, which had once hung from hooks in the window, had been taken down too. Intrigued at the change, the photographers spoke with Kurowycky again.

"The inspections done by the city have become steadily more aggressive over the past few years and risk extinguishing our Old World traditions. I walk into my store now and I want to cry," he told them. "It used to look really full and always smelled wonderful. Food is a very visual item and this place looks like it’s going out of business tomorrow." He said that his profit margins had fallen 20 percent since city officials forced his meat into basement refrigerators.

In 2007, Kurowycky's turned the refrigerators off and closed its doors for good. The business had been owned by the family for over half a century.

James and Karla Murray published Store Front - The Disappearing Face of New York in 2008, which featured photographs of storefronts taken mostly between 2004 and 2007. Ten years later, they have decided to return to the storefronts as a way to chronicle New York City's changing landscape.

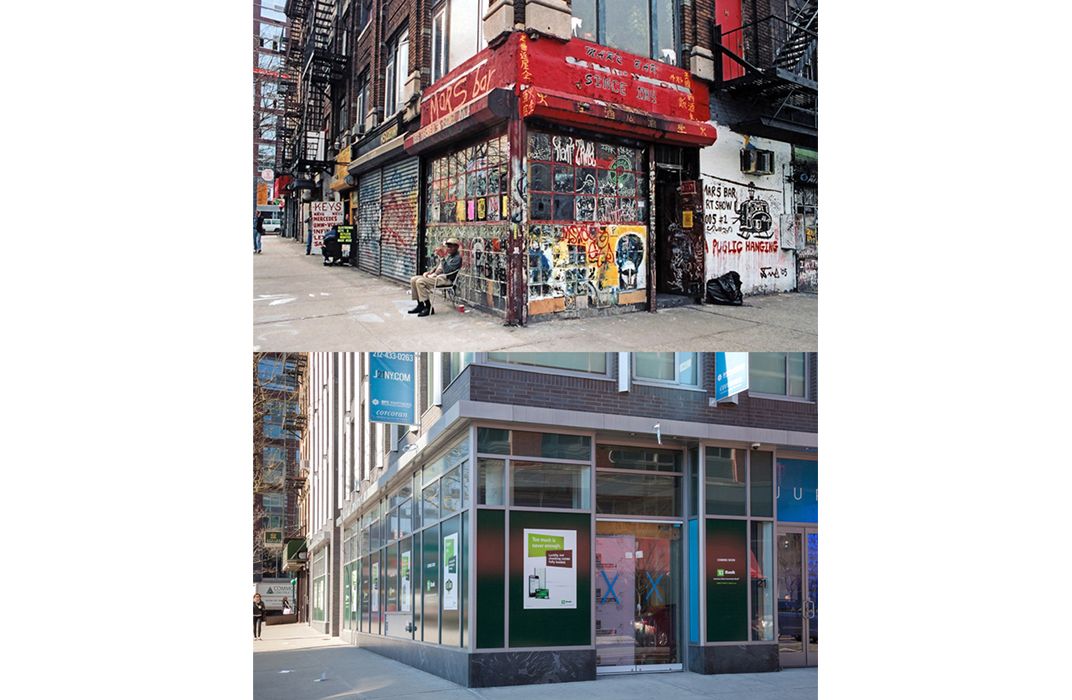

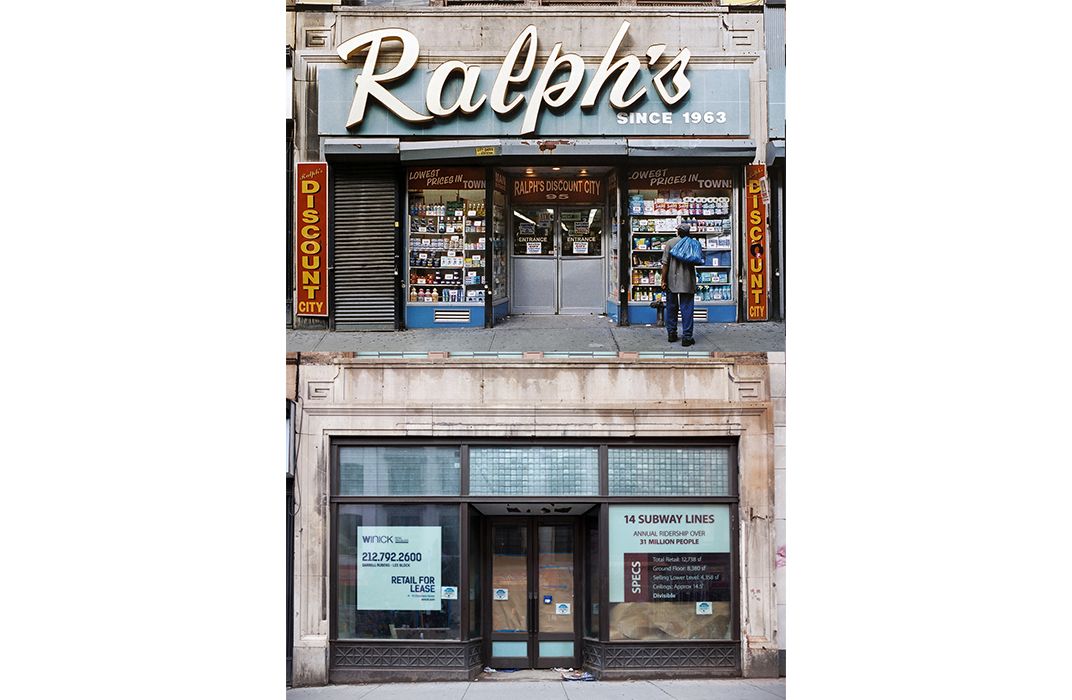

"The changes we have seen in the storefronts of NYC for the most part are unsettling to us because many traditional 'mom and pop' neighborhood storefronts that had prevailed in some cases for over a century were disappearing in the face of modernization and conformity and the once unique appearance and character of New York's colorful streets were suffering in the process," the photographers said over e-mail.

In some instances, as with Kurowycky's, the steady march of modernization (and movement away from Old World traditions) drove down profit margins. But in other cases, an influx of wealthier residents drove up real estate costs to where a family-owned business could no longer afford to rent their space.

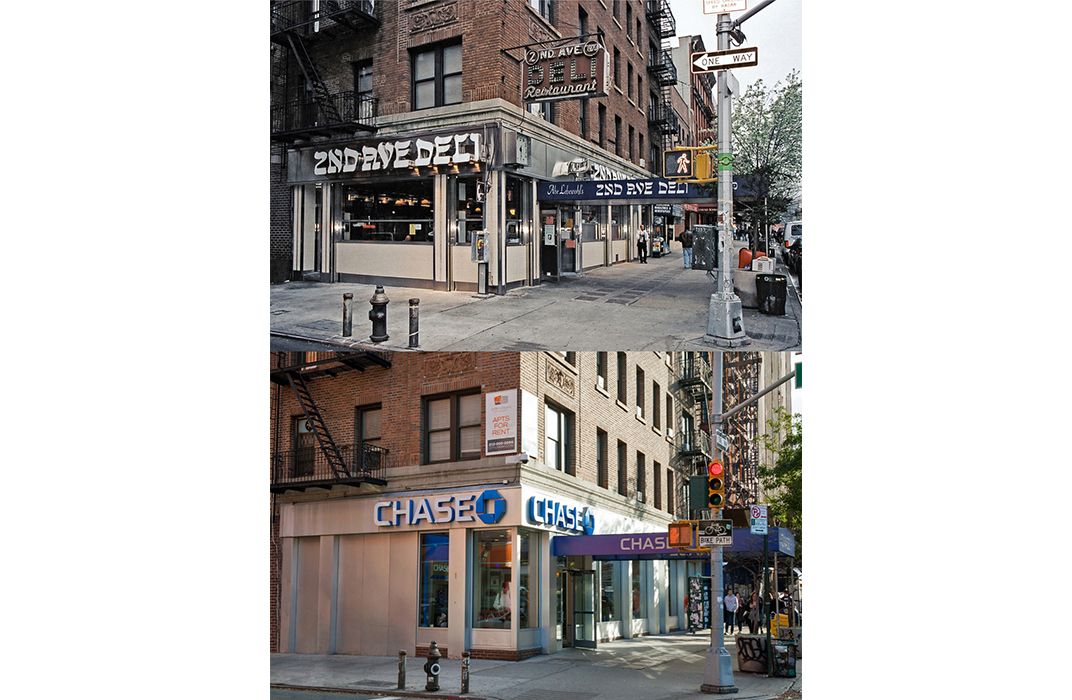

"We noticed very early on while photographing the original stores that if the owner did not own the entire building, their business was already in jeopardy of closing. The owners themselves, frequently acknowledged that they were at the mercy of their landlords and the ever-increasing rents they charged," they wrote. "When the original 2nd Avenue Deli location in the East Village closed in 2006 after the rent was increased from $24,000 a month to $33,000 a month, and a Chase Bank took over the space, we knew the contrast of before and after was severe."

Gentrification—the influx of residents, usually middle to upper class, into an urban area who in turn cause an uptick in property values and rent—is nearly as old as human history: historians note incidences of gentrification in Ancient Rome, when wealthy residents and commercial property owners bought out poorer areas to build large markets and villas. But interest in the concept and effect of gentrification has renewed since the 1970s, when urban life began to regain a level of prestige it had lost following decades of "white flight" to America's suburbs. Debates rage as to whether or not gentrification is detrimental to the fabric of the American city, but it's impossible to argue that gentrification doesn't, for better or worse, change the basic structure of the neighborhoods in which it occurs.

That is something that James and Karla Murray have seen happen first hand in their own neighborhood, New York's East Village.

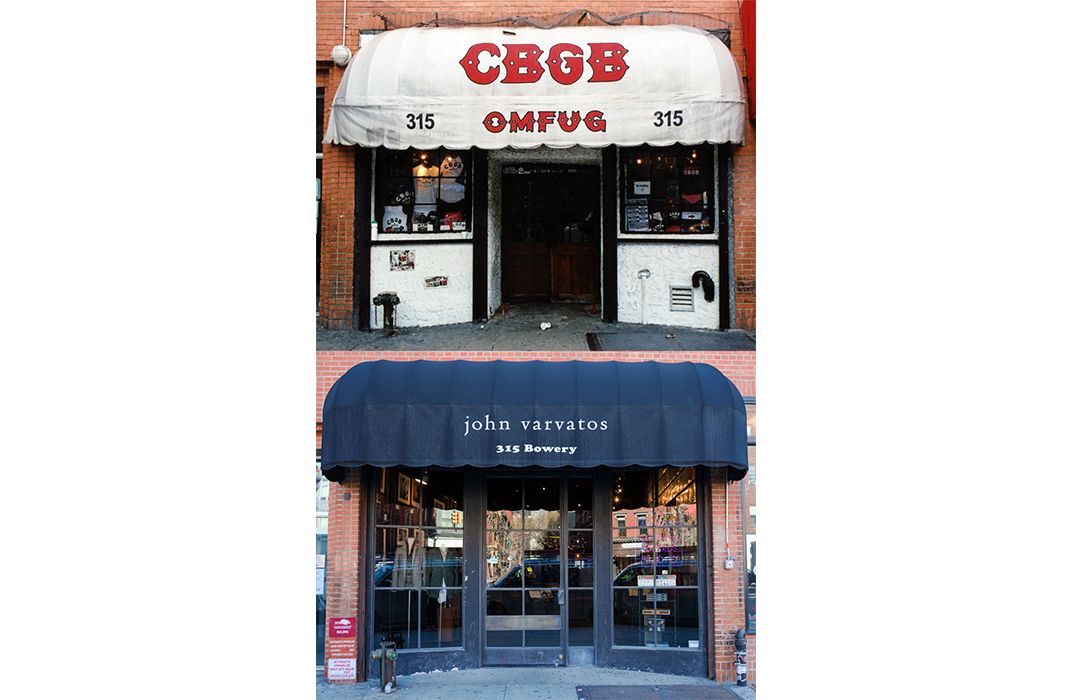

"Another startling change in our own neighborhood of the East Village was the closure of CBGB in 2006 after it lost its lease. It was replaced by a high-end fashion boutique, John Varvatos," they explained. "No iconic locale seemed safe any longer."

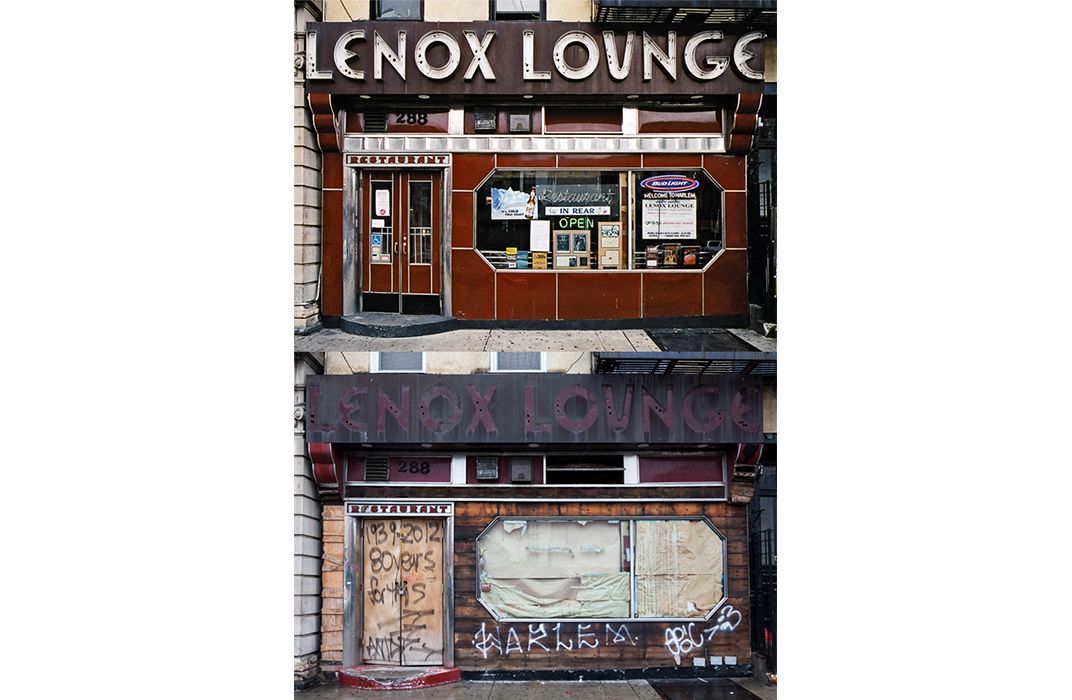

In some places, their photographs capture community backlash against the displacement of these iconic businesses. In their most recent photograph of the Lenox Lounge, for example, a graffiti-writ message appears across the now-empty lounge's boarded-up door: 1939-2012/80 years/For this. During the Lenox Lounge's 80-year operation, it became one of the city's iconic jazz institutions, hosting artists such as Billie Holiday, John Coltrane and Miles Davis. Now, the building sits empty, closed on December 31, 2012, due to a lease dispute.

The negative aspects of gentrification have been argued by long-time neighborhood residents, who like the graffiti on the Lenox Lounge door, worry that an influx of new residents dampens the historical culture of an area. Director Spike Lee illustrated such a complaint earlier this year, when he responded to a New York Times article that argued the benefits of gentrification.

"I mean, [white people] just move in the neighborhood. You just can’t come in the neighborhood. I’m for democracy and letting everybody live but you gotta have some respect," Lee told an audience in Brooklyn on February 25. "You can’t just come in when people have a culture that’s been laid down for generations and you come in and now s--- gotta change because you’re here?"

James and Karla have seen similar sentiments from longtime residents through their project—in the East Village, where the pair lives, residents have created a community coalition to promote the importance of supporting local, family-owned businesses.

"When these shops fail, the neighborhood is aversely affected. These old storefronts have the city's history etched in their facades. They set the pulse, life, and texture of their communities," James and Karla wrote.

Not all of the storefronts that James and Karla originally photographed fell victim to the changing urban landscape, however. By their estimate, 40 percent of the businesses they photographed remain, though some have changed their storefronts, replacing their old hand-painted signage with plastic awnings. Other businesses folded, but were replaced by equally small, independently owned stores, like Kim's Video, which took over the space once occupied by Kurowycky's.

Completing the project has given James and Karla a new perspective on the changing landscape of their community. "We have learned that although cities like New York have always been synonymous with change, we never realized how heavily the deck was stacked against an independently-owned small business and how a way of life for many residents is rapidly disappearing," they wrote.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/natasha-geiling-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/natasha-geiling-240.jpg)