Oklahoma City Is Becoming a Hotspot for Vietnamese Food

Southeast Asian immigrants are spicing up America’s fast-food capital with banh mi, curried frogs’ legs and pho

:focal(-771x6428:-770x6429)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a2/13/a2137297-4f3d-4263-a3b2-8101f699712a/mar2016_k02_vietnamfoodcol.jpg)

Oklahoma City’s culinary reputation was cemented in 2007, when Fortune magazine declared it the nation’s fast-food capital, with the highest number of “heavy users” of the burger and chicken joints year after year.

So perhaps it’s not the first place you’d look for some of the nation’s finest examples of that ultimate slow food, the Vietnamese soup called pho. Why is it a slow food? Because beef bones simmer for hour upon hour, while the chef’s key job is to skim off the fat. All you want is broth. Clean.

In fact, “clean” is the word we heard most often to describe the food we were eating in the savory days we spent in Oklahoma City’s thriving Vietnamese community. We were sitting one lunchtime in Mr. Pho, a thriving soup bar in the heart of the city’s official Asian district, a 20-block enclave with at least 30 Vietnamese restaurants. Across the table were Mai McCoy and Vi Le, who both arrived in the United States as young children shortly after the fall of Saigon.

“My mother makes a new batch of pho every week,” Vi says. “It takes forever—you’re boiling bones, skimming the fat, boiling some more. But once you’ve clarified that broth, then you start adding ingredients back in, one at a time, each its own distinct flavor. First the noodles, then the slices of beef, and then—at the table—the basil leaves, the lime, the Sriracha hot sauce. You’re layering flavors. It’s like with pasta. Do you want to put parmesan on it? Do you want fresh ground pepper?”

“Every item in there is identifiable,” says Mai.

We repeat to the two women what the city’s hottest young Vietnamese chef, Vuong Nguyen, had told us the night before. “You have to be able to taste every single ingredient. No muddling things together in a mush.”

“Exactly right,” says Vi. “As far as my parents are concerned, there’s no reason for casseroles to exist.”

**********

Elsewhere in our reporting, we’ve encountered immigrant communities, newly arrived, struggling to make their way in the new world. But the Vietnamese began arriving in Oklahoma 40 years ago, so by now a second and third generation have set down relatively secure and prosperous roots.

But, oh, the beginning was tenuous. Pretty much everyone we talk to begins their story with a boat and a narrow escape.

Mai McCoy, who was 6 when she left Vietnam, was shipwrecked with her family on a Malaysian peninsula, where they were greeted by soldiers with machine guns. “There were more than 200 people on this fishing boat—everyone had paid with gold bars. The people who paid more were up on deck. Down below it was...not good. My sister was frail, and my dad was holding her up to the porthole just to get some fresh air somehow. On the Malaysian beach, they had a little rice porridge to eat. My [other] sister remembers it falling in the sand, and she remembers eating it sand and all because she was so hungry. Food is still comfort to her.”

Ban Nguyen made it out on a plane, but his father-in-law, Loc Le, whom he describes as the great tycoon of South Vietnam, lost everything when the Communists won, using his last money to buy a boat and cramming others aboard. “They got out as far as a freighter, and the freighter wanted to just give them some water and let them keep going. But my father-in-law clung to the freighter’s anchor line. ‘Take us aboard or we’ll die.’” He ended up running a tiny breakfast restaurant in Oklahoma City, Jimmy’s Egg, which Ban has now grown to a 45-restaurant chain.

**********

In 2008, the owners of the Super Cao Nguyen market, Tri Luong and his wife, Kim Quach, raised funds to bring a replica of one of those overcrowded fishing boats to the small park near their store for a few days. “I could see all the memories coming back to my father’s eyes,” says Remy Luong, their youngest son.

But by that point the fear was long since gone, and Oklahoma was long since home. Super Cao Nguyen (“my father saw Super Walmart and Super Target, so he added it to the name of the central highlands in Vietnam, which was a touch of home,” says Remy’s brother Hai) has gone from a store with a few aisles selling dry Asian noodles to a behemoth Asian market, busy all day and absolutely packed on weekends with shoppers from all over the state and beyond, speaking at least 20 different languages. “It’s a melting pot,” says Hai. “I’ve had people come in and they are in tears because they’ve found a product from back home they’ve been missing for years.” The bakery spins out a thousand baguettes a day—Vietnam, of course, spent much of its recent history as a French colony, so the French influenced its cuisine in overt and subtle ways. Some of those baguettes are made into the store’s classic—and filling—banh mi sandwiches. Three dollars will get you the number one, cha lua (pork loaf): ham, headcheese, pâté, butter, pickled carrots, daikon and jalapeño. “In Vietnam the food has to be transportable,” Remy says. “That’s how the banh mi was born.”

In other aisles you can buy duck balut (eggs with a partially developed embryo, making a crunchy treat) or basil-seed beverage (a very sweet drink with texture) or brawny-looking buffalo fish. A hand-lettered sign, with more recently added English translations, lets you choose from 12 different ways to get your fish, beginning with “Head On, Gut Out, Fin Off.” “We have 55,000 items and between my brothers and my parents we’ve tried them all,” says Remy. “We’re all big foodies. We eat, sleep, dream food. When some customer comes to us with an idea for some product we should carry, the first thought that pops into our head is, ‘That sounds delicious.’” And most of it does, though sometimes a little gets lost in the English translation: We didn’t go out of our way to sample “gluten tube” or “vegetarian spicy tendon.”

We joined Remy—named for the premium French cognac—at the nearby Lido Restaurant for a lunch of bun bo Hue (a lemongrass-based beef soup), curried frogs’ legs and clay pot pork, braised in the Coco Rico coconut soda that his market sells by the case. “When my parents got to [their first neighborhood in Fort Smith, Arkansas], it was mostly crack houses,” he says. But their obsessive hard work—his newly arrived father worked the morning shift shucking oysters and the night shift in a chicken factory—let them open the small store there and eventually buy the Oklahoma City supermarket, which Remy and Hai run with their brother, Ba Luong, and their parents, who refuse to retire. “Our mom is still in charge of the produce,” Hai told us, adding that some of it, like the bitter melon and the sorrel-like perilla, is grown by “little old ladies” from the neighborhood. “Not working is not in our parents’ DNA.”

Lido was the first Vietnamese restaurant with an English menu in the Asian district, but now “you throw a rock and you hit a good pho place,” Remy says. As we talk, more dishes keep arriving: a fried egg roll with ground shrimp and pork, a hot-and-sour catfish soup.

“The traditional way is to pour soup into the rice bowl and eat a little bit of soup first before moving on to the other dishes,” Remy instructs. The catfish is buttery soft and nearly melts in the mouth, with the cool ngo—the Vietnamese term for cilantro—providing a counterpunch to its warmth. And then we turn to the frogs’ legs—another nod to the French—which are bathed in curry and buried in vermicelli and, yes, taste like chicken, and the fresh spring rolls, and the fried spring rolls, and the clay pot with its coconut-caramelized pork, and the crisp fried squid and the shrimp with broken rice, which is made from fractured grains. “In Oklahoma you can never order enough food,” says Remy as we load up our plates. “In Oklahoma there are three things that bring people together: football, food and family.”

**********

Though the Sooners game is on in the Lido and in Super Cao Nguyen and everywhere else we go, the Vietnamese reverse that Oklahoma trinity: “Family is almost like breathing for me,” Vi Le told us. “When my husband, who’s Caucasian, was courting me, I told him he had to pass muster with the whole family, including my brother. He was like, ‘You mean my future depends on what a 13-year-old boy thinks of me?’ And I was like, ‘Yep. I can live without you, but I can’t live without my family.’” He passed the test, in no small part because he had a strong appetite for her mother’s cooking. (The wedding was a ten-course Vietnamese dinner at the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum. “It’s all about the food at the wedding,” Mai says. “You have to have duck, because it’s considered the most elegant dish.” “The fried rice isn’t till the end,” adds Vi. “My college friends were like, ‘Why did you wait to serve the fried rice? We love fried rice!’ But for us, it’s ‘Why fill up with rice when you have the duck?’”)

“My husband had to reroof my parents’ house,” adds Mai. “He had to re-fence the yard, mow the lawn, take my mother to the store. He had to pay his dues.” But those dues were small compared with the investment the parents had made in their children. Her parents worked the evening shift as janitors at a Conoco refinery, home for half an hour at 9 to eat dinner with the kids and check to make sure they’d done their homework. “The only thing they had when they got here was time. And they spent that time at work to get the dollars to make a life for us.”

“For Americans, it’s like figuring out what your dream job is, or some nonsense like that,” says Vi, who is now general counsel for a major hospital system. “But that was not in the equation for my parents. They wanted that for me, but for them, though they’d been successful in Vietnam, they never looked back. Just to have a job was wonderful. Never being dependent on anyone, making your own way. My dad was always like, ‘If you make a dollar, you save 70 cents.’”

“Money was not a taboo topic,” says Mai. “The bills got paid at the kitchen table. When my mother would talk with someone, it was like, ‘How much do you make an hour? What are the benefits? What will you do next?’” “When I was a little girl,” Vi says, “I apparently asked the American woman next door, ‘Why do you stay home? You could be making money.’”

Perhaps because of that poverty and that drive, the Vietnamese have often excelled in their new home. Ban Nguyen, who runs the chain of breakfast eateries, went to Oklahoma State five years after arriving in the United States with “zero English.” His grades, he says, were mediocre, but he learned something more important for an entrepreneur: “I joined a fraternity. I might have been the first Asian guy to ever get in one at OSU. And yeah, they called me Hop Sing [the fictional Chinese cook in the television show “Bonanza”] and all that. But if you live with 80 guys in a frat house, you learn how to get along with people. I can talk with anyone,” he said, in a soft Oklahoma drawl—and indeed he’d given hugs or high-fives to half the customers eating eggs and pancakes in the store that day. “I think I’m more American than Vietnamese, more Okie from Muskogee than anything else. But in my head I still think in Vietnamese—those are the words. And, of course, there’s the food. My kids don’t like me sometimes because I like to go out for Asian food when they want Cheesecake Factory, or some big national brand.”

**********

Many of the Vietnamese we talked to—second-generation Americans, though most had been born abroad—were worried, at least a little, that their children might lose sight of the sacrifices their parents had made to make their lives here possible. “I have fears for my kids that they won’t understand the struggle—and that they won’t like the food,” says Mai. “But my 6-year-old, he’ll eat the huyet,” a coagulated blood cake. “And my 2-year-old, his face is all the way down in the pho when he eats it.”

“This generation doesn’t want to eat pho so much,” says Vuong Nguyen, the chef whose Asian fusion cooking at Guernsey Park, on the edge of the Asian district, earned a passionate following. “For them it’s like, ‘Have you had that amazing cheese steak? Have you had that pizza from over there? But the good thing is, everyone else is getting into Vietnamese food.”

He grew up with his grandmother. “Cooking is all she does. She just cooks. She wakes up and starts breaking down fish. You get up and there’s breakfast waiting. And when you’re having breakfast, she’s saying, ‘Hey, what do you want for lunch?’” He took that early training, added a two-and-a- half-year apprenticeship at Oklahoma City’s famed restaurant The Coach House and began producing food that has to be eaten to be believed. “When the owners approached me and said they had a location right on the border of the Asian district and the artsy bohemian district, I said, ‘I have the cuisine you’re looking for.’ It was easy-peasy for me. Most of the stuff on the menu I made up in one try. You could say it’s Asian-inspired home comfort food with French techniques.”

Meaning that he’s using all the tools of the high-powered modern chef (dehydrating kimchi and then grinding the result into a fine powder, say) to recreate the sharp, distinct tastes of classic Vietnamese dishes. At Guernsey Park, his Scotch egg, for instance, resembled the classic Asian steamed bun, except that the pork sausage is on the outside, a shell of spiced flavor surrounding a perfect soft-boiled egg, with croutons made from steamed-bun dough to soak it all up. Last year Nguyen opened his own well-regarded breakfast and brunch eatery, Bonjour, just north of the Asian district.

Go there sooner rather than later, because chef Nguyen isn’t staying in Oklahoma too much longer. This son of the immigrant experience—where people were so grateful to be in a stable, peaceful nation that they clung like barnacles to the new land—is preparing to head out into the vast world himself. As with many of his generation, the shy and retiring stereotype of his forebears no longer applies. “I want to expand my mind,” he says. “YouTube doesn’t do it for me anymore.” One of the first stops will be Vietnam, where he plans to work a “stage,” or short-term apprenticeship, in some of the country’s great eateries. “But I need to go, and soon. My wings are spread so far I’m hitting people in the face.”

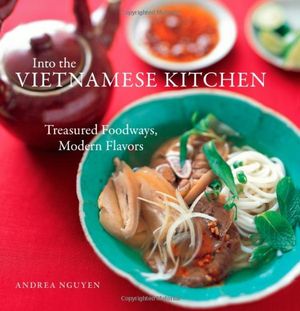

Into the Vietnamese Kitchen

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/halpern_mckibben-edited.jpg)