On the Job: Courtroom Sketch Artist

Decades of depicting defendants, witnesses and judges have given Andy Austin a unique perspective on Chicago

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/sketch-artist-631.jpg)

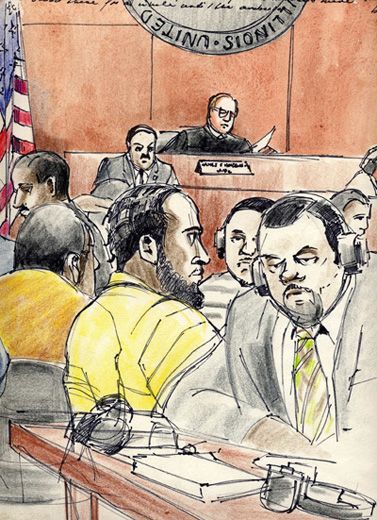

In the late 1960s, Andy Austin began sketching scenes and people around the city of Chicago. Her wanderings eventually led her to the courtroom and a job as a sketch artist for a local Chicago television news station. Over the years, she's drawn three indicted governors and countless judges, witnesses, plaintiffs and defendants. While on break from sketching the Tony Rezko proceedings last spring, Austin discussed the famous trials and faces she's depicted and her recent book, Rule 53: Capturing Hippies, Spies, Politicians and Murderers in an American Courtroom (Lake Claremont Press, April 2008).

How did you get into this line of work?

Well, I was really lucky, because in one impulsive moment, I got the job that I've had for almost 39 years. I was drawing, just for myself, at this high profile trial called the Chicago Conspiracy Eight trial, a year after the Democratic Convention of '68 when protesters clashed with police in the parks of Chicago. I was trying to draw in the spectator section, and the deputy marshals came along and took away my pad and pens. I continued to draw, and I sort of drew surreptitiously on a little marketing list, and I drew on the pages underneath the list, but it didn't work. I managed to get myself into the press section by bothering the judge. While I was there, one day I overheard a local TV reporter complaining that he needed a sketch artist the next day, so without thinking I just went up to him. I don't know what I said, but he looked at my drawings and he said to me "Color these," and I said, "Sure." When I got home, I had a telephone call from the ABC network that they wanted me to be their artist the next day.

What kind of artistic training or background did you have?

I had about two years of art school after college. I went to Europe the summer after graduating from college, and I just felt I had to stay in Europe—it was such an incredible experience. I'd never taken any art in college, but I studied art there [in Florence] after a fashion. You know, there was no real teaching—I went to the museums and was given permission to draw from original old master drawings at the Uffizi Gallery, which is just an incredible experience. I thought, well I will try to be an artist. So I went to art school at the Boston Museum School [School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston] where you had to mix your own pigments, you had to skin egg yolks to make egg tempura, and you had to do perspective and anatomy and all of these things. And I was there for two years.

What is your average day like?

I work for TV news, and they don't plan things the day before—I mean they can't. I talk to my assignment desk every morning, and I usually don't know the day before where I'm going to work the next day, and I really like it that way. On the other hand, when I'm covering an ongoing, really important trial the way I am now with Tony Rezko, I know every day that I'm going to go to that trial. My deadline depends on what show they're going to use the drawings in, but I consider my deadline almost always to be between 2:30 and 3:00 in the afternoon and then the drawings are shot by cameras in the lobby of the courthouse. I continue drawing the rest of the day, in case something new happens—a new witness or very important witness or to get a head start on the next day. There are certain things in the trial that aren't going to change, so you can kind of work ahead of time.

What do you think is the most interesting part of your job?

Listening to what goes on in court. I mean, it's not a good place for an artist—the lighting is usually bad and often you can't see or you can't get close enough to the witness.

Why I love the job so much is the variety and the education that you get sitting in court and listening to people. I mean, I'm just amazed at the things I hear and learn, and it sounds corny but it sort of creates a portrait of the city—all parts of the city.

What was the most exciting moment on the job?

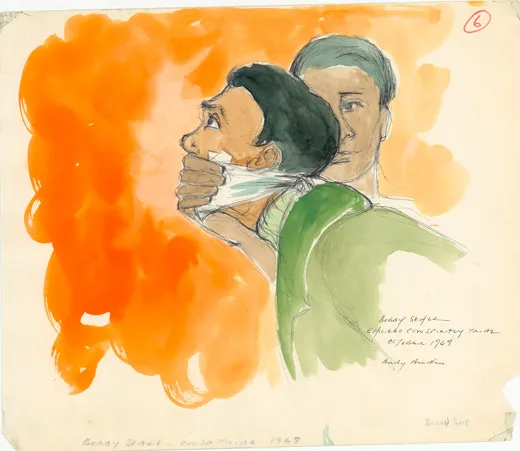

Well, the most exciting moment was in the very beginning during the Chicago Conspiracy trial. One of the indicted men, a Black Panther named Bobby Seale, wanted to wait for his own lawyer to defend him [his lawyer was ill], but the judge refused to let him have his own lawyer. He said that the lawyers for the other defendants could stand in and defend him perfectly well, so Bobby Seale tried to defend himself. [The judge never agreed to let Seale defend himself and found his outbursts in contempt of court.] He would rise to his feet and on cross-examination try to question the government's lawyers, and he was forcibly put into his seat by federal marshals every time. He got more and more angry and he yelled at the judge, and they finally bound and gagged him in the courtroom.

I was not in the courtroom at that very moment because I'd been instructed to go back to the station to have my sketches shot so they could get to New York in time for the national news. So I had left the courtroom when this man was gagged and bound to a chair, and the next few days he was brought into court strapped to a chair with an ace bandage around his head and a gag in his throat. However, he managed to tip the chair over whereupon all the defendants got up and started fighting with the marshals. Everybody's screaming and yelling, and I was supposed to be drawing this! In those days they were really casual about where they let people sit and we in the press sat right next to the defense table—we had little folding chairs and we could sit right there. The fighting was so intense that the chairs were knocked over and we had to get up and move out of the way, and it was really a mess. That was too exciting—I mean that practically undid me.

Do you think about objectivity or keeping bias out of your sketches when you're sketching?

My feeling is that I should try to be as accurate and as straightforward and as honest as possible, and editorializing in any way is just not something I would ever do. The interesting thing I discovered as time went on—it's best that I don't think at all about what I'm drawing. I'm totally absorbed in what I'm hearing, and I draw better, much better, that way. If I start to become self-conscious about the drawing in any way I just mess up. The main thing is to get the likeness and the likeness comes not only from doing the features as accurately as possible but also the gestures, the way somebody stands or sits.

What advice do you have for someone going into this field?

One piece of advice is always dress well. You want to sort of camouflage that you don't belong there and so many artists dress as artists. It's so important to blend in and look as if you belonged in the courtroom. As far as advice beyond that, you have to be enormously flexible. You also have to be willing to put on the air stuff that you're not particularly proud of sometimes. It took me awhile to realize I wasn't always going to be able to do my best work, but they needed it and they needed it quickly and that was it. I mean I couldn't have any vanity about waiting until I got a good sketch. You have to work fast, you have to put it on the air and you have to not worry too much.