One Writer Used Statistics to Reveal the Secrets of What Makes Great Writing

In his new book, data journalist Ben Blatt takes a by-the-numbers look at literary classics and finds some fascinating patterns

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/18/f5/18f57e77-7d71-4a26-8ac5-9570d61de258/reading.jpg)

In most college-level literature courses, you find students dissecting small portions of literary classics: Shakespeare’s soliloquies, Joyce’s stream of consciousness and Hemingway’s staccato sentences. No doubt, there is so much that can be learned about a writer, his or her craft and a story’s meaning by this type of close reading.

But Ben Blatt makes a strong argument for another approach. By focusing on certain sentences and paragraphs, he posits in his new book, Nabokov’s Favorite Word is Mauve, readers are neglecting all of the other words, which, in an average-length novel amount to tens of thousands of data points.

The journalist and statistician created a database of the text from a smattering of 20th century classics and bestsellers to quantitatively answer a number of questions of interest. His analysis revealed some quirky patterns that might otherwise go unnoticed:

By the numbers, the best opening sentences to novels do tend to be short. Prolific author James Patterson averages 160 clichés per 100,000 words (that’s 115 more than the revered Jane Austen), and Vladimir Nabokov used the word mauve 44 times more often than the average writer in the past two centuries.

Smithsonian.com talked with Blatt about his method, some of his key findings and why big data is important to the study of literature.

You’ve taken a statistical approach to studying everything from Where’s Waldo to Seinfeld, fast food joints to pop songs. Can you explain your method, and why you do what you do?

I am a data journalist, and I look at things in pop culture and art. I really like looking at things quantitatively and unbiased that have a lot of information that people haven’t gone through. If you wanted to learn about what the typical person from the United States is like, it would be useful, but you wouldn’t just talk to one person, know everything about them and then assume that everything about people in the United States is the same. I think one thing with writing that kind of gets lost is that you can focus on one sentence by an author, especially in creative writing classes, or one passage, and you lose the bigger picture to see these general patterns and trends that writers are using over and over again, hundreds and maybe thousands of times in their own writing.

So what made you turn to literature?

My background is in mathematics and computer science, but I’ve always loved reading and writing. As I was writing more and more, I became very interested in how different writers and people give writing advice. There’s a lot of it that made sense but seemed not backed up by information, and a lot of it that conflicted with each other. I just thought there had to be a way to take these topics in writing that people were already well aware of and talking about and test them on great authors and popular authors to see if this advice is real or if it is prescriptive advice that doesn’t really mean anything in the real books and the real pages.

What was the first question you wanted to ask about literary classics and bestsellers?

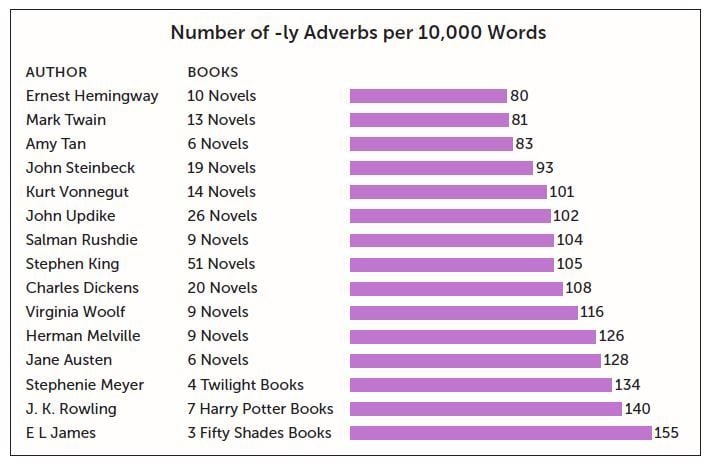

The first chapter in the book is on the advice of whether or not you should use –ly adverbs. This is also the first chapter I wrote chronologically. It’s mostly on Stephen King’s advice not to use –ly adverbs in his book On Writing, which for a lot of writers is the book on writing. But lots of other writers—Toni Morrison, Chuck Palahniuk—and any creative writing class advises not to use an –ly adverb because it is an unnecessary word and a sign that you are not being concise. Instead of saying, “He quickly ran,” you can say, “He sprinted.”

So I wanted to know, is this actually true? If this is such good advice, you’d expect that the great authors actually do use it less. You’d expect that amateur writers are using it more than published authors. I just really wanted to know, stylistically, first if Stephen King followed his own advice, and then if it applies to all the other great and revered authors.

So, what did you find?

In fact, there is a trend that authors like Hemingway, Morrison and Steinbeck, their best books, the ones that are held up and have the most attention on them now, are the books with the fewest amount of –ly adverbs. Also, if you compare amateur fiction writing and online writing that’s unedited with bestsellers and Pulitzer Prize winners of recent times, there is a discrepancy, where less –ly adverbs are used by the published authors. I am not so one-sided that I think you can just take out the –ly adverbs from an okay book and it becomes a great book. That’s obviously not how it works. But there is something to the fact that writers who are writing in a very direct manner do produce books that overall live the longest.

How did you go about creating a database of literary works?

For many of the questions, I was using the same 50 authors I had chosen somewhat arbitrarily. Essentially it was based on authors that were on the top of the bestseller list, authors that were on top of the greatest authors of all time list and authors that just kind of represented a range of different genres and times and readers. That way, throughout the book, you can compare these authors and get to know them.

It was very important to me that if I said something like, “Toni Morrison uses this word at this rate,” I was talking about every single novel she’s ever written and not just the three that I happen to already have. In my book, there are 50 to 100 authors that are referred to throughout. I found their bibliographies and then found all their novels that they had written up to that point as their complete record. In some ways, it is a bit like keeping sports statistics, where each book is kind of like a season and then all of these seasons or books come together as a career. You can see how authors change over time and how they do things overall. Once you have all the books on file, then answering these questions that in some ways are very daunting is very straightforward.

And how did you process all that text?

There is a programming language called Python, and within that, there is a set of tools called the Natural Language Toolkit, often abbreviated NLTK. The tools involved in that are freely available to anyone. You can download the package online and use it in Python or other languages. You can’t get many of the writing questions in particular, but you can say, how many times does this word appear in the text? It can go through and identify where sentences end and where sentences begin, and parts of speech—adjective vs. adverb vs. verb. So once you have those tools, you can get the data.

What stats did you compile manually? What was the most tedious?

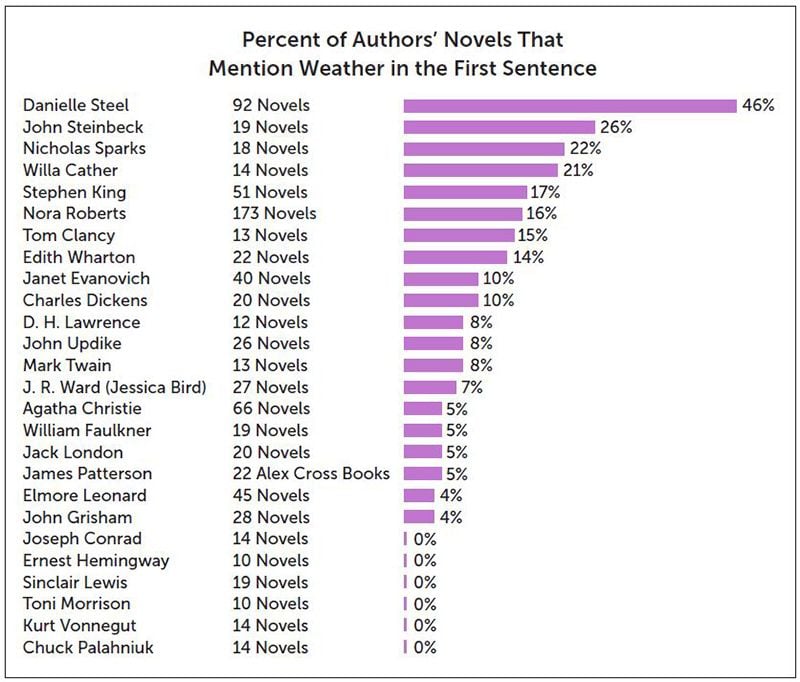

There is one section where I look at opening sentences. Elmore Leonard, who was a very successful novelist, had said, “Never open a book with weather.” This is also advice found in a lot of writing guides. So I went through hundreds of authors to see how often they open their book on weather. For example, Danielle Steel, I believe 45 percent of her first sentences in books are about the weather. Many times it’s just “It was a magnificent day,” or “It was bright and sunny out,” things like that. For that, there was no way to do that automatically without having some error, so I would just go through all the book files and mark whether there was weather involved. You can say it was tedious, because it was a lot of data collected, but it was kind of fun to go through and read hundreds of opening sentences at once. There are other patterns that clearly emerge from authors over time.

Like you say, tedious for some, fun for others. Some might think this analytical approach is boring, but you argue that it can be “amusing” and “often downright funny.” What was your funniest finding?

The title of the book, Nabokov’s Favorite Word Is Mauve, is about how, by the numbers, the word that he uses at the highest rate compared to English is mauve. That ends up making a lot of sense if you look at his background, because he had synesthesia. He talked, in his autobiography, about how when he heard different letters and sounds, his brain would automatically conjure colors.

I repeated that experiment on 100 other authors to see what their favorite word is. As a result, you get three words that are representative of their writing by the words they use most. Civility, fancying and imprudence. That’s Jane Austen. I think if you saw those words, Jane Austen might be one of your first guesses. And then you have an author like John Updike, who is a bit more gritty and real and of a different time. His favorite words are rimmed, prick and fucked. I think seeing the personality come through based on these simple mathematical questions is very interesting. If you have a favorite author, going through it does sort of reveal something about their personality you may not have noticed before.

Ray Bradbury had written that his favorite word was cinnamon. By the numbers, he does use that a lot. His explanation of why he liked cinnamon was that it reminded him of his grandmother’s pantry. So I went through and found other spice words and smell words that could be associated with a grandmother’s pantry, and Ray Bradbury does use most of those words at a very high rate. In some sense, you can get this weird, Freudian look into something about authors’ childhoods. If Ray Bradbury hadn’t said that, maybe you could still figure it out.

You compared American and British writers, confirming a stereotype that Americans are loud. Can you explain this one?

This one was actually based originally on a study done by a graduate student at Stanford. He had identified words that are used to describe dialogue in books, and described them as loud, neutral or quiet. “Whispered” and “murmured” would be under quiet. Neutral would be “he said” or “she said,” and loud would be “he exclaimed” or “shouted.” I went through the 50 authors that I looked at, as well as large samples of fan fiction, and found, not by a crazy margin but a meaningful margin, that Americans do have a higher ratio of the loud words to the quiet words. There are a few explanations. It could be that that is how Americans talk throughout all of their lives, so that is the way that writers describe them talking frequently. You could also just see it as American writers having a preference for more action-based, thriller, high tempo stories compared to the more subtle ones. Americans are indeed louder by the numbers.

Why do you think applying math to writing is a good way to study literature?

I am definitely not advocating that this should be the first way you study literature if you are trying to improve your writing. But even a novel of moderate length is probably 50,000 words, and that’s 50,000 data points. You’re just not going to be able to soak that all in at once, and there are going to be some questions that you just can’t answer reading through on your own. It’s good to see the bigger picture. If you sit down and study one paragraph, you’re in your creative writing class talking to your professor, if there is a set way to look at that, you are just going to see that throughout everything. But with the data, that kind of frees you of it, and you can answer some questions without these biases and really get some new information.

You mention that you kept thinking back to Roald Dahl’s “The Great Grammatizator.”

There is a great Roald Dahl story where essentially an engineer devises a way to write a story. In this doomsday scenario, someone can just give the machine a plot and it will spit out a final novel. The insinuation there is that they are producing novels that are so formulaic and basic. The protagonist in that story chooses not to join the operation of the machine and fights against it by creating his own writing and art.

I definitely think that this book, if you are into writing, will answer a lot of questions for you and definitely change the way you think about some things, but ultimately there is really no replacement for ideas that make people think and scenes that make people fearful or connect with the characters. This book is looking at the craft of writing and not necessarily how to create a memorable story. This book is not trying to engineer a perfect novel, and I don’t think we are as close to that as some people may fear.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)