Painter Alexis Rockman Pictures Tomorrow

There’s trouble ahead in the artist’s eerie yet riveting paintings, now the subject of a major exhibition

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Alexis-Rockman-Hurricane-and-Sun-631.jpg)

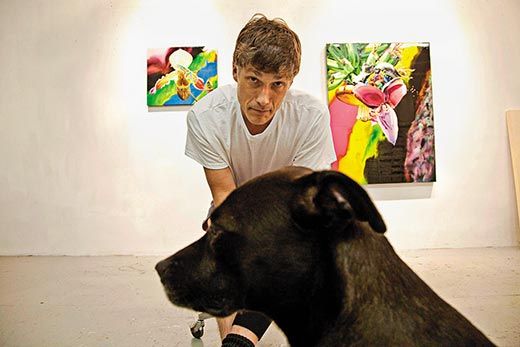

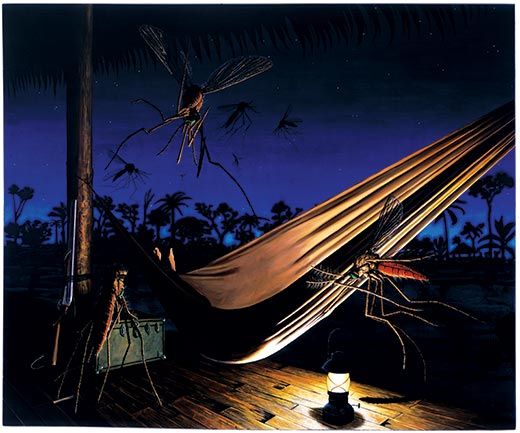

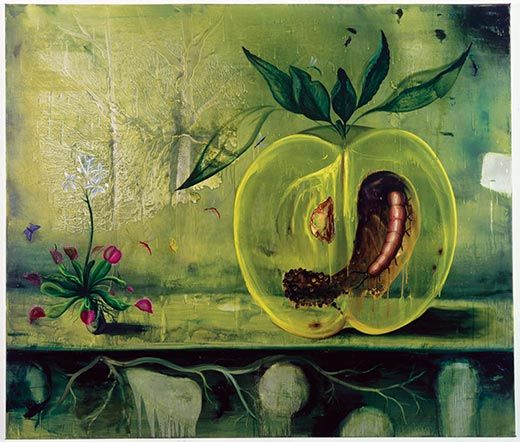

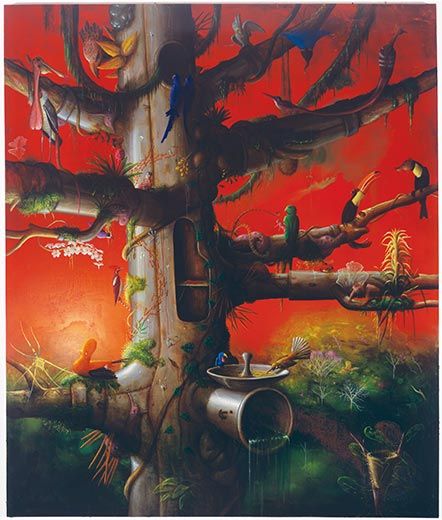

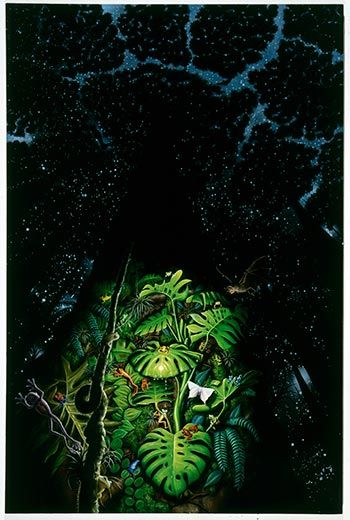

"I try not to collect things," Alexis Rockman says, standing in front of a glass-front cupboard in his white-walled studio in Lower Manhattan. The cabinet holds dead animals given to him by friends: a mongoose devouring a cobra, stuffed birds, a bat with outstretched wings, an armadillo. There's also a photograph of the artist at age 7, wearing a toothy smile as he holds up an Eastern box turtle. The passions of that little boy, who grew up in New York City haunting the American Museum of Natural History, are deeply embedded in his extravagantly beautiful, disquieting paintings of a post-apocalyptic natural world, for which the artist, now 48, is increasingly well known. If Rockman's early love of flora, fauna and museum dioramas has informed his grown-up work, so, too, has a boyish delight in monsters, sci-fi movies and popular culture.

Despite its displays of surrealistic wit, his art has long been freighted with a serious message about environmental degradation. "Rockman has been among the very few [artists] trying to understand the deep, mysterious, and crucial cleavage between the human and natural worlds," the environmentalist Bill McKibben wrote.

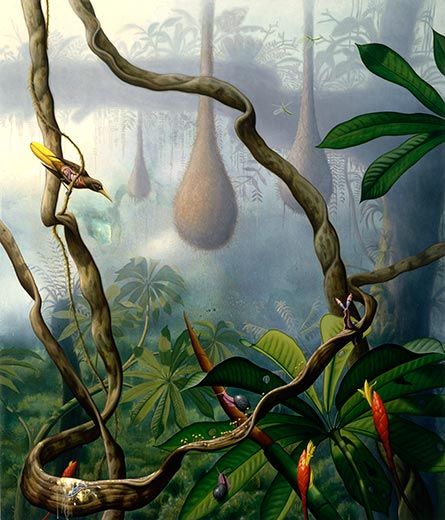

Now the artist is the subject of a major retrospective at the Smithsonian American Art Museum (SAAM). The catalog includes an essay by his friend Thomas Lovejoy, the scientist who first used the term "biological diversity." "His vision is based on a real understanding of what's going on," Lovejoy says of Rockman's paintings. "It's a surrealism that is seriously anchored in reality." The two met in 1998 after Rockman made several paintings to accompany an article on the Amazon basin that Lovejoy wrote for Natural History magazine.

"Alexis is an exceptional painter," says Joanna Marsh, the museum's curator of contemporary art, "and his interest in the environment, in natural history and in 19th-century landscape painting resonates with our museum collection and the Smithsonian-wide emphasis on natural science and biodiversity."

Rockman, who is tall and square-jawed, describes his childhood as one devoted less to studying than drawing and basketball, which he still plays. But a concern for the larger world was part of his upbringing by "hippie parents," as he calls them. His mother is an urban archaeologist; his late father was a jazz musician. After a stint at the Rhode Island School of Design, Rockman earned a B.F.A. at the School of Visual Arts in New York City. When he began his career as a painter, in the 1980s, the idea of realism was so far out of fashion he thought of his offbeat landscapes as conceptual art.

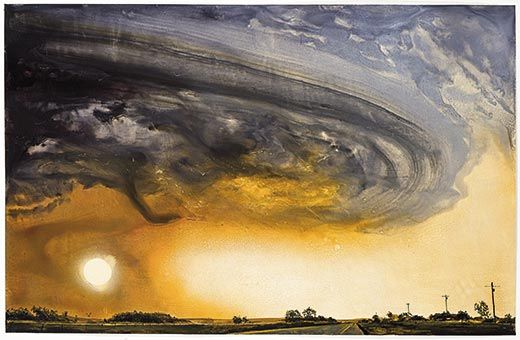

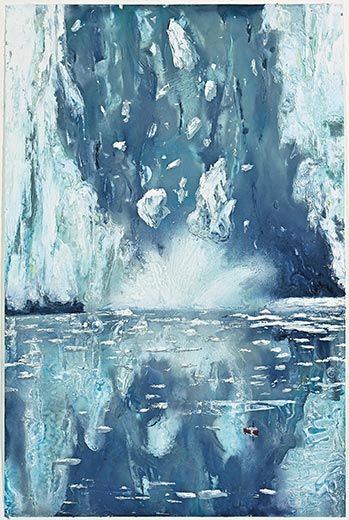

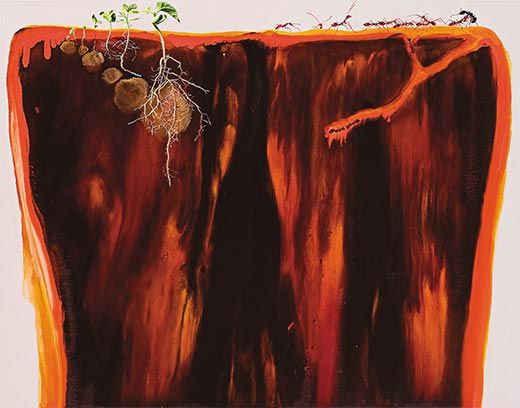

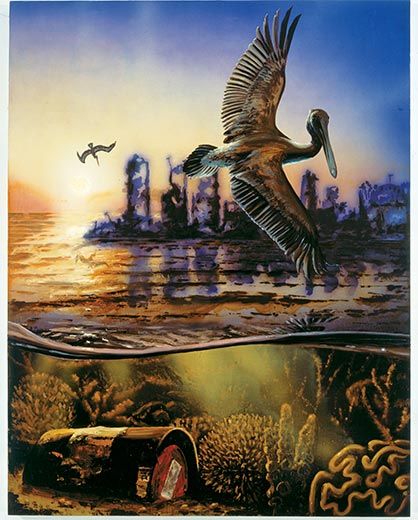

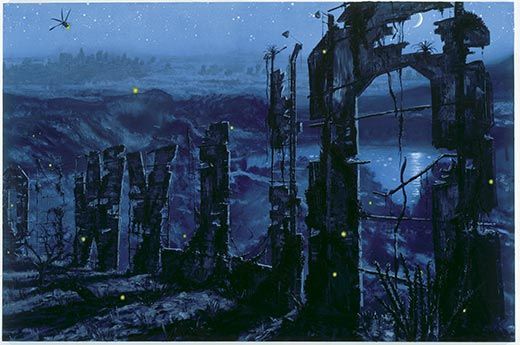

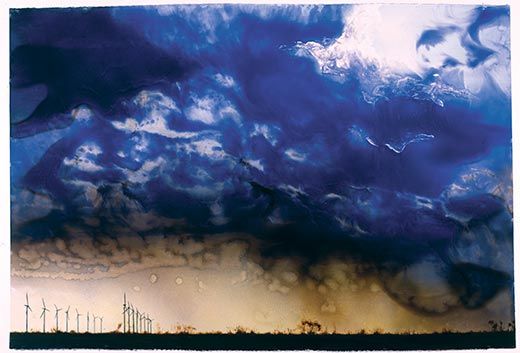

Three epic murals that help define the painter's trajectory anchor the SAAM show of 47 artworks. Evolution (1992), a bright and riotous primeval landscape, with a nasty swamp and a spewing volcano, is alive with mutant and prehistoric creatures. Manifest Destiny (2004) is a strangely gorgeous depiction of Brooklyn, New York, far in the future, when global warming has reduced it to a toxic wetland. And South (2008), inspired by a trip to Antarctica, is what the artist calls "a group portrait of ice"; painted with oil on paper, it is looser and lighter than his earlier, densely detailed paintings. He used a similar technique in two of his "weather drawings" in 2006, the eerie Hurricane and Sun, with its sickly yellow disk dimming beneath a spiraling gray tempest, and Calving Glacier.

A world-class eco-tourist, Rockman has also trekked to Guyana, Tasmania and Madagascar to research his work. But he creates the actual paintings in his studio, based on his photographs, sometimes manipulated with Photoshop software, and images he culls from the Internet. He has consulted scientists and architects, too, who suggest what a horrifically degraded future might look like for paintings such as Washington Square.

Recently he finished a big painting called Mesopotamia for the new U.S. embassy in Baghdad. It depicts the Tigris-Euphrates ecosystem before civilization. And he is fulfilling his boyhood passion for movies and animation by collaborating on sequences for director Ang Lee's film version of Life of Pi. The more distant future seems less certain. "I have no idea what I'm going to be doing, let alone anyone else," he says. "But I hope there's enough energy and time to make art, if civilization still exists."

Cathleen McGuigan, who is based in New York City and writes about the arts, profiled Alex Katz in the August 2009 issue.