Political Animals: Republican Elephants and Democratic Donkeys

Politicians and parties may flip-flop but for more than 100 years, the political iconography of the Democratic donkey and the Republican elephant has remained unchanged

![]()

Typical contemporary illustrations of the Democratic donkey and the Republican elephant

In a few days, America will elect our next president. It’s been a particularly contentious and divisive campaign, with party lines not so much drawn as carved: red states vs. blue states; liberals vs. conservatives; Republicans vs. Democrats. While party platforms change and politicians adapt their beliefs in response to their constituency and their poll numbers, one thing has remained consistent for more than 100 years: the political iconography of the democratic donkey and the republican elephant.

The donkey and elephant first appeared in the mid-19th century, and were popularized by Thomas Nast, a cartoonist working for Harper’s Magazine from 1862-1886. It was a time when political cartoons weren’t just relegated to a sidebar in the editorial page, but really had the power to change minds and sway undecided voters by distilling complex ideas into more compressible representations. Cartoons had power. And Thomas Nast was a master of the medium, although one who, by all accounts, was churlish, vindictive and fiercely loyal to the Republican party. In fact, it’s said that President Lincoln referred to Nast as his “best recruiting general” during his re-election campaign. These very public “recruiting” efforts led Nast to create the familiar political symbols that have lasted longer than either of the political parties they represent.

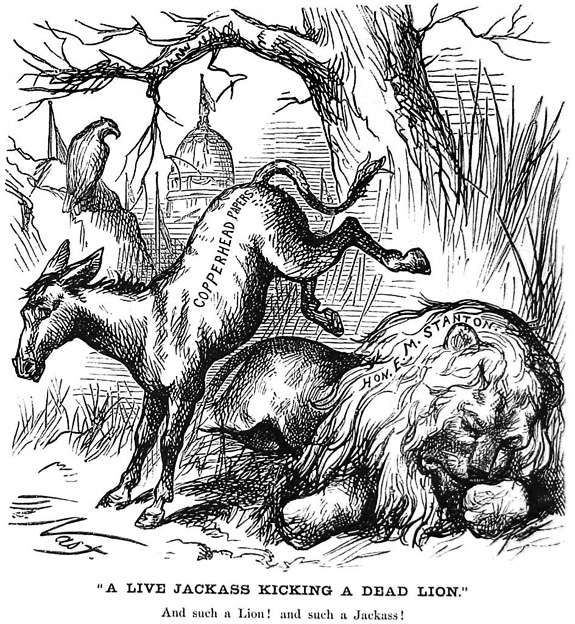

The 1870 Harpers cartoon credited with associating the donkey and the Democratic Party

On January 15, 1870, Nast published the cartoon that would forever link the donkey to the Democrat. A few ideas should be clear for the cartoon to make sense: First, “republican” and “democrat” meant very different things in the 19th century than they do today (but that’s another article entirely); “jackass” pretty much meant the exact same thing then that it does today; and Nast was a vocal opponent of a group of Northern Democrats known as “Copperheads.”

In his cartoon, the donkey, standing in for the Copperhead press, is kicking a dead lion, representing President Lincoln’s recently deceased press secretary (E.M. Stanton). With this simple but artfully rendered statement, Nast succinctly articulated his belief that the Copperheads, a group opposed the Civil War, were dishonoring the legacy of Lincoln’s administration. The choice of a donkey –that is to say, a jackass– would be clearly understood as commentary intended to disparage the Democrats. Nast continue to use the donkey as a stand-in for Democratic organizations, and the popularity of his cartoons through 1880s ensured that the party remained inextricably tied to jackasses. However, although Thomas Nast is credited with popularizing this association, he was not the first to use it as a representation of the Democratic party.

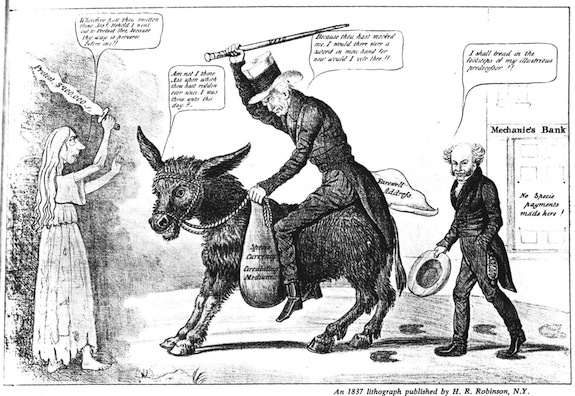

An 1837 lithograph depicting the first appearance of the Democratic donkey.

In 1828, when Andrew Jackson was running for president, his opponents were fond of referring to him as a jackass (if only such candid discourse were permissible today). Emboldened by his detractors, Jackson embraced the image as the symbol of his campaign, rebranding the donkey as steadfast, determined, and willful, instead of wrong-headed, slow, and obstinate. Throughout his presidency, the symbol remained associated with Jackson and, to a lesser extent, the Democratic party. The association was forgotten, though, until Nast, for reasons of his own, revived it more than 30 years later.

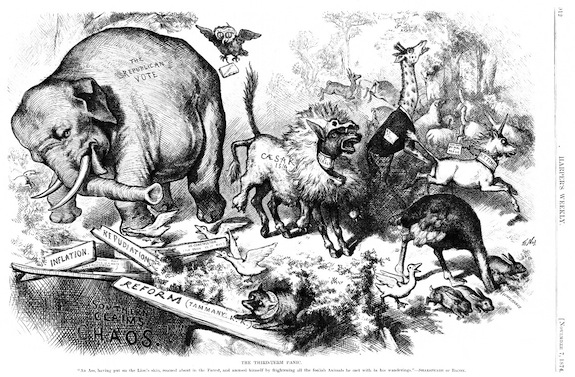

“The Third Term Panic: An ass, having put on the Lion’s skin, roamed about in the forest, and amused himself by frightening all the foolish Animals he met with in his wanderings.” Thomas Nast for Harpers, 1874.

In 1874, in yet another scathing cartoon, Nast represented the Democratic press as a donkey in lion’s clothing (though the party itself is shown as a shy fox), expressing the cartoonist’s belief that the media were acting as fear mongers, propagating the idea of Ulysses S. Grant as a potential American dictator. In Nast’s donkey-in-lion’s-clothing cartoon, the elephant –representing the Republican vote– was running scared toward a pit of chaos and inflation. The rationale behind the choice of the elephant is unclear, but Nast may have chosen it as the embodiment of a large and powerful creature, though one that tends to be dangerously careless when frightened. Alternately, the political pachyderm may have been inspired by the now little-used phrase “seeing the elephant,” a reference to war and a possible reminder of the Union victory. Whatever the reason, Nast’s popularity and consistent use of the elephant ensured that it would remain in the American consciousness as a Republican symbol.

Like Andrew Jackson, the Republican party would eventually embrace the caricature, adopting the elephant as their official symbol. The Democrats, however, never officially adopted the donkey as a symbol. Nonetheless, come election season, both animals lose any zoological significance in favor of political shorthand. For while candidates may flip and flop, legislation may be stripped or stuffed, and political animals may change their stripes, the donkey and elephant remain true.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jimmy-Stamp-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jimmy-Stamp-240.jpg)