President Obama’s Autopen: When is an Autograph Not an Autograph?

When the President signed the fiscal cliff deal from 4,800 miles away, he did it with the help of a device that dates back to Thomas Jefferson

![]()

The modern Autopen “Atlantic” models (original image: Autopen.co)

President Obama was in Hawaii when he signed the fiscal cliff deal in Washington D.C. last week. Of course, it’s now common for us to send digital signatures back and forth every day, but the President of the United States doesn’t just have his signature saved as a JPEG file like the rest of us lowly remote signatories. Instead, he uses the wonder that is the autopen – a device descended from one of the gizmos in Thomas Jefferson’s White House.

President Barack Obama’s signature.

It would take a well-trained eye to spot the difference between a hand-written signature and an autosignature. Even though it is essentially the product of a soulless automaton, the robotically signed signature is usually perceived to be more authentic than a rubber stamp or digital print because it is actually “written” by a multi-axis robotic arm (see it in action on YouTube). The autopen can store multiple signature files digitally on a SD card, meaning that a single device can reproduce everything from John Hancock’s John Hancock to Barack Obama’s. The machines are small enough to be portable and versatile enough to hold any instrument and write on any surface. We can’t know the exact details of Obama’s autopen because, as one might expect of a machine capable of signing any document by the “Leader of the Free World,” the White House autopen is kept under tight security (a fact that lends itself so well to the plot of a political thriller or National Treasure sequel, I can’t believe it hasn’t been made yet). Yet we do know a few things about the Presidential auto-autographer.

Harry Truman was the first President to use one in office and Kennedy allegedly made substantial use of the device. However, the White House autopen was a closely guarded secret until Gerald Ford’s administration publicly acknowledged its use. Traditionally, the autopen has been reserved for personal correspondence and documents. More recently though, it has taken on a higher profile role in the White House. Barack Obama was the first American President to use the autopen to sign a bill into law, which he first did on May 26, 2011 when he authorized an extension of the Patriot Act from France. And now he’s used it again to approve the fiscal cliff deal from more than 4,800 miles away and, in so doing, has returned the autopen to the national spotlight.

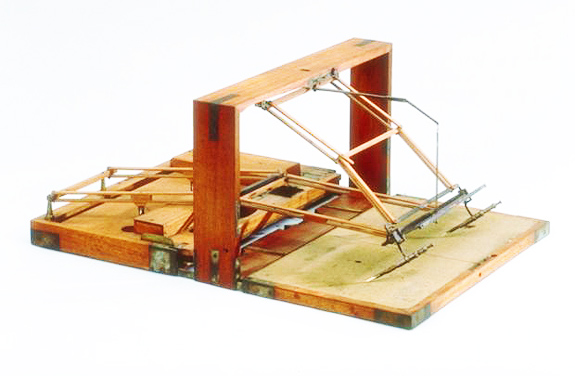

Though the autopen wasn’t used in the White House until the 1950s, the history of the automated autograph dates back much further. A precursor of sorts to the autopen, the polygraph, was first patented in 1803 by John Isaac Hawkins and, within a year, was being used by noted early adopter Thomas Jefferson. Known formally as the “Hawkins & Peale’s Patent Polygraph No. 57,” this early copy device was used by Jefferson to make single reproductions of documents as he was writing them. Though the device’s inventor referred to the copy machine as a “polygraph,” today it would be more properly called a pantograph – a tool traditionally used by draftsmen and scientists to reduce and enlarge drawings. According to the OED, it wasn’t until 1871 that the word “polygraph” gained its modern definition: a machine that detects physiological changes and is often used as a lie detector. Prior to that date, and for some years after, it was used to refer to early copying devices.

Thomas Jefferson’s “polygraph” device. (image: Monticello)

Whatever you call it, Jefferson’s polygraph was a beautifully crafted marvel composed of two multi-axis mechanical arms, each holding a single pen, joined together by a delicate armature. As Jefferson wrote with one pen, the other moved synchronously, simultaneously producing an exact copy of his document, letting the Technophile-in-chief retain personal copies of his letters – copies that have since proven invaluable to historians. Jefferson referred to the copying machines as “the finest invention of the present age” and owned several different types of reproduction machines, some of which even included his own custom modifications. But the polygraph was by far his favorite. In a letter to Charles Willson Peale, who held the American patent rights to the machine, Jefferson wrote that “the use of the polygraph has spoiled me for the old copying press, the copies of which are hardly ever legible…I could not, now therefore, live without the Polygraph.” The machine was so critical to Jefferson’s daily life that he kept one at the White House and one at Monticello, where it can still be seen in his home office. The White House polygraph is on display at the National Museum of American History.

Though obviously less advanced than the autopen, and used for a different purpose, the polygraph is similar in that it ultimately created a signature that wasn’t technically written by the President. While both devices are incredibly convenient, they raise an important question: is a signature still a signature when it’s not written by hand?

Digital media theorist and architectural historian Mario Carpo has written extensively on the relationship between early reproduction methods and modern digital technologies. In his excellent book, The Alphabet and the Algorithm, Carpo notes that ”like all things handmade, a signature is a visually variable sign, hence all signatures made by the same person are more or less different; yet they must also be more or less similar, otherwise they could not be identified. The pattern of recognition is based not on sameness, but on similarity.” That statement may seem obvious, but it’s important. The variability of a signature denotes its authenticity; it reflects the time and place a document was signed, and perhaps even reveals the mood of the signatory. A digital signature, however, has no variability. Each signature –one after another after another– is exactly like the last. Although the modern autopen includes adjustable settings for speed and and pressure, these options are used for practical purposes and variability is only created as a side-effect. Today, the notion of a signature as a unique, identifiable mark created by an individual, is a concept that may be changing. The signature of a historic figure is no longer a reliable verification of authenticity that attests to a specific moment in history, but a legal formality.

However, that formality has also been debated. The legality of the automated signature was questioned by some members of Congress after President Obama’s historic use of the autopen in 2011 but precedent for the issue had already been established. In 2005, at the request of President George W. Bush, the Supreme Court White House Office of Legal Council issued a 30-page opinion memorandum stating that the President may indeed use an autopen to sign bills and other executive documents. The Court noted that while they “are not suggesting that the President may delegate the division to approve and sign a bill…he may direct a subordinate to affix the President’s signature to the bill.” So, legally speaking, while the autopen’s robotic writing is not a signature, it’s not not a signature.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jimmy-Stamp-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jimmy-Stamp-240.jpg)