Remembering the Astrodome, the Eighth Wonder of the World

Fifty years after its grand opening, the spectre of the Houston stadium still looms large

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/32/43/3243cfa8-1c2d-47ce-b446-c3c09472ad57/apr2015_d06_phenom.jpg)

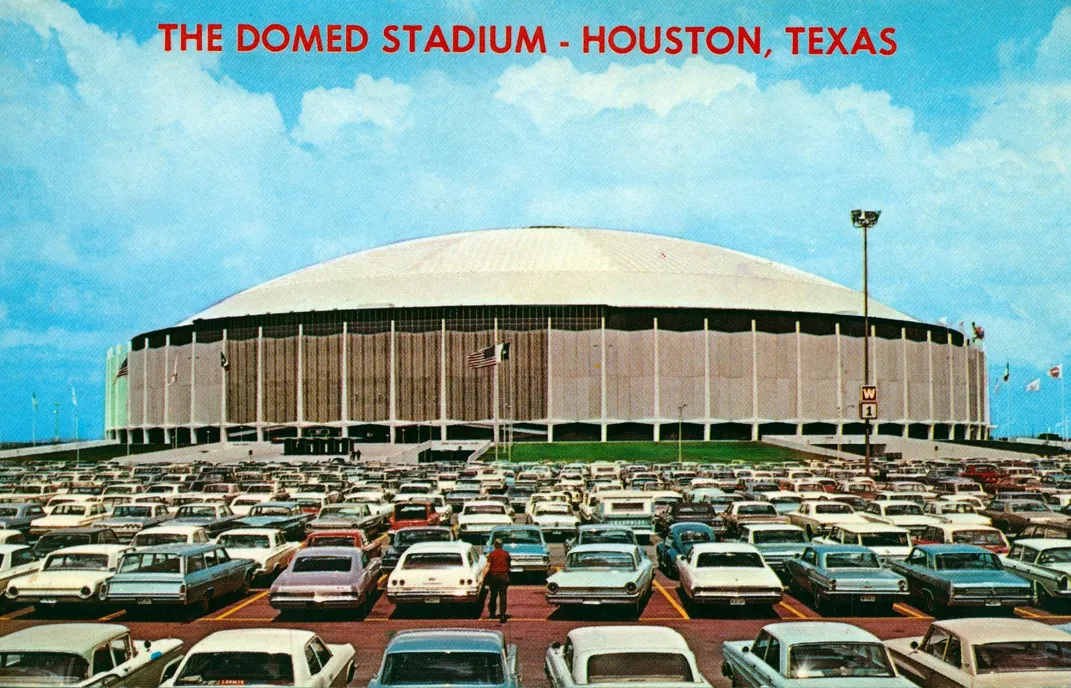

It was the past’s vision of the future. The greatest dome ever conceived, a climate-controlled wonderland of science and cutting-edge engineering, the biggest indoor space ever made by man, an immense decorated cylinder with a flying-saucer roofline. Half-a-mile around, it was as big as Houston’s dream for itself, as big as the idea of Texas.

Next month marks the 50th anniversary of the opening of the Houston Astrodome, one of many wonders once dubbed the Eighth Wonder of the World. Before Star Wars and “Star Trek,” there were Sputnik, John Glenn and the Jetsons, back when every elementary school cafeteria was filled with metal lunchboxes painted with astronauts and rocket ships. Back when we all believed technology could save us.

The idea of a domed stadium wasn’t new, but it took Judge Roy Hofheinz, a larger-than-life Houston booster, to make it happen. He sweet-talked and strong-armed the city fathers until in 1962 they found themselves—all Brylcreem and two-button suits, Stetsons and heavy shoes—breaking ground on the new home of football’s Oilers and baseball’s Colt 45s not with shovels but with six-guns.

When the building opened, three years later, the renamed Astros beat the Yankees in an exhibition game. It was April 9, 1965. Mickey Mantle hit major-league history’s first indoor home run, but it was the building people talked about. It was everything they said it would be. But it was not then, and is not now, very beautiful.

It wasn’t the curve and counter-curve of Googie-style coffee shops, of ’50s spaceships and San Fernando car washes. Nor was it Eero Saarinen’s lighter-than-air TWA terminal at JFK. Except for its scale, the Astrodome was a shape out of the past, a Colosseum on the bayou.

It was twice as large as any single enclosure ever built before. The immense greenhouse ceiling was a marvel, like the great train sheds of Victorian Europe—but once the Astros outfielders started losing fly balls in the glare, the transparent ceiling was painted over. Which meant the grass died, which meant “AstroTurf” had to be invented. A year later it was America’s third most-visited man-made attraction after the Golden Gate Bridge and Mount Rushmore. Between innings the grounds crew wore spacesuits and helmets and cleaned the diamond with vacuums.

Elvis filled the place more than once. Everyone from Evel Knievel and Muhammad Ali to Billy Graham and the Supremes had their names on the marquee. Bobby Riggs and Billie Jean King fought the “Battle of the Sexes” here in 1973 (women won), and Nolan Ryan threw one of his seven no-hitters under that unlikely ceiling. Refugees from Katrina washed up here in the hurricane summer of 2005. Like Ellis Island, and not without controversy, it briefly held, housed, then redistributed thousands of them.

By then it was long since clear that the Astrodome was an anachronism. Its replacement since 2002, a gigantic pole barn now called NRG Stadium—get it?—was built beside it, so close that each subtracts from the other in a way every architecture student but no developer or politician understands.

Proposals float up, weightless, to repurpose the emptied Astrodome, reclaim its greatness. No one pulls the trigger. The Astrodome isn’t saved—but somehow it isn’t gone. It’s the perfect avatar of its time, big enough to hold our space age optimism and allay our space age fears.

When the time comes, all you can do is abandon it.

The Astrodome: Building an American Spectacle

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jeff_MacGregor2_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jeff_MacGregor2_thumbnail.png)