Rhyme or Cut Bait

When these fisher poets gather, nobody brags about the verse that got away

The last weekend in February is a slow time for Pacific Northwest and Alaska fishermen. The crab season is winding down, and the salmon aren't running yet. But in Astoria, Oregon, a historic fishing town on the Columbia River, there's real excitement as commercial fishermen gather to read or perform their poems, essays, doggerel and songs. Harrison "Smitty" Smith, a Harley rider and, at 79, the event's oldest poet, observes:

According to a fisherman

Whose name was Devine,

'The world's a cafeteria

You get one trip through the line.'

Playing to overflow crowds for three days and two nights at local art galleries, a bar, and a café, the eighth-annual Fisher Poets Gathering features more than 70 presenters, from Kodiak, Alaska, to Arcata, California. "We're a far-flung but tightknit community, so it's more of a reunion than a pretentious literary event," says Jon Broderick, a high-school English and French teacher, who heads up to Alaska with his four sons every summer to fish for salmon. Broderick, college professor Julie Brown and historian Hobe Kytr founded the conclave in 1998, taking inspiration from the annual National Cowboy Poetry Gathering in Elko, Nevada. "Just as in the cowboy life, the fisherman's life is given to long periods alone in which to contemplate his work, his life and the cosmos, so why should it come as any surprise that fishermen are deep?" Kytr says.

A rapt audience listens to Dave Densmore, a burly 59-year-old veteran fisherman with shoulder-length graying hair and hands indelibly stained with engine grease, as he reads an ode to his son, Skeeter. The boy died along with Densmore's father in a boating accident on Skeeter's 14th birthday, 20 years ago.

Several years later in Alaska,

Skeeter got his first big buck

He'd hunted and stalked it, hard, alone

Had nothing to do with luck.

Y'know I still watch that hillside

I guess I'm hoping for some luck

To see the ghost of my son

Stalking the ghost of that big buck.

John van Amerongen, the editor of the Alaska Fisherman's Journal, which has published fisher poetry for more than 20 years, says that the genre preceded written language and can be traced to a time "when fishermen battling the elements told their stories in rhyme because they were easier to remember." Since the 1960s, commercial fishing vessel radios have helped popularize fisher poetry. "Before then there was limited boat-to-boat communication," he says. "Now fishermen could while away long hours at sea when waiting for the fish to bite by sharing recipes, stories and poems."

Several of the fisher poets are women, who have made inroads in the male-dominated industry. "It's an old superstition that it's bad luck to have women on a boat," says van Amerongen. "But women have to be tough to overcome the raised eyebrows and the leers, in addition to doing their job on deck." Take pseudonymous "Moe Bowstern," 37, a Northwestern University English literature graduate who landed a job on a halibut boat in Kodiak, Alaska, in 1990. "My first task was to haul in a halibut as big as me," she recalls. "I'm straddling this huge fish—they can weigh 300 pounds—and it's bucking under me. I felt like I was on a bronco." Bowstern’s duties have ranged from chopping and loading bait for crab pots to setting seine nets for salmon. She reads a blunt confessional:

"I arrived with a college degree, a smart mouth and a thirst for alcohol. I quit drinking cold turkey after that first summer....I've replaced that demon alcohol with this fishing. Yes, it's dangerous, but....More of my friends...are lost to alcohol and drugs and suicide and cancer than boat wrecks. And fishing is a lot more fun...."

Pat Dixon became a regular at the Astoria reading after the Alaskan cannery he fished for closed five years ago. "When I discovered that many people were going through similar experiences," he says, "I realized I wasn't alone in my grief. I began to express how I felt in writing; in hearing others' stories and my own, I began to heal." Dixon's poem "Fat City in Four Directions" concludes:

We ride the ebb and swell of the job market,

negotiating interviews like we used to quarter

the boat through heavy weather.

we still run hard, looking for jumpers,

We still search for Fat City.

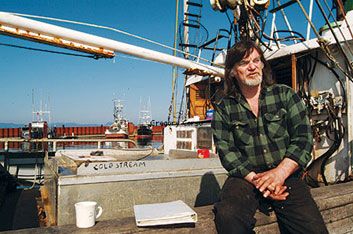

Later that Saturday night in the Voodoo Room, folks in the audience are asking one another, "Do you think Geno will show up?" Wesley "Geno" Leech, 55, who has worked as a merchant seaman and a commercial fisherman, is the dean of fisher poetry. But the previous night he was too sick with pneumonia to read. Then, suddenly, applause erupts, heads swivel, and the crowd parts to let Leech through. Wearing black sweat pants and a weathered Navy peacoat, he strides to the microphone in an entrance worthy of Elvis. Leech doesn't just recite his poetry; he closes his eyes and bellows each stanza, rocking back and forth as if on a rolling deck in high seas.

They're clingin' to the cross trees

Plastered to the mast

Splattered on the flyin' bridge

Bakin' on the stack....

We're buckin' back to Naknek

Festooned with herring scales....

If the Japanese eat herring roe

And the French escargot snails

How come there ain't a gourmet market

For all them herring scales?

On Sunday morning, the fisher poets and about a hundred of the 700 people who paid $10 each to hear them, jam the Astoria Visual Arts Gallery for an open-mike session. Smitty Smith, recovering from injuries he suffered when a truck rammed his Harley, limps to the microphone. "I had a lot of time thinking about coming back here and I sure wasn't disappointed," he says.

Joanna Reichhold, a 29-year-old woman who has been fishing off the coast of Cordova, Alaska, for five seasons, dedicates her last song—"My lover was a banjo picker, and I'm a picker of fish"—to Moe Bowstern. Bowstern waves the airplane ticket that will take her to Alaska this very night, where she's hopping on a boat to fish for crab in Marmot Bay.

By noon people are spilling out onto the sidewalk under an overcast sky. "The last several years I thought it was just us old guys making poems, but now the younger people are coming up," says co-founder Jon Broderick. "Smitty staggering up and pulling out a poem. Three or four generations of people telling their stories. I about teared up. I tell you, I felt like I was at a wedding."