Roman Splendor in Pompeii

Art and artifacts reveal the elaborate maritime pleasure palaces established by Romans around the Bay of Naples

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Wall-painting-House-of-the-Golden-Bracelet-631.jpg)

If you’ve been to the Italian coast south of Rome you probably want to return. Picturesque scenery, mild weather, fertile soil and the teeming sea provide a banquet for the senses, and the easy pace of life leaves plenty of time for reverie and romance. The ancient Greeks founded the colony of Neapolis (Naples) along this stretch of Mediterranean coast around 600 B.C.; half a millennium later, the colony was absorbed by the Roman Empire. By the first century B.C., the Bay of Naples, a single day’s sail from the hustling imperial capital, had become the favorite vacation spot of the Roman elite. The entire region from Puteoli (modern Pozzuoli) in the north to Surrentum (Sorrento) in the south, embracing towns such as Pompeii and Herculaneum, was dotted with richly adorned villas of extraordinary splendor. The great Roman orator and statesman Cicero dubbed the Bay “the crater of all delights.”

The lifestyles that wealthy Romans enjoyed in their second homes is the subject of “Pompeii and the Roman Villa: Art and Culture Around the Bay of Naples,” an exhibition on view at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. through March 22. The show, which will also travel to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (May 3-October 4), includes 150 objects, mainly from the National Archaeological Museum in Naples, but also on loan from site museums at Pompeii, Boscoreale, Torre Annunziata and Baia, as well as from museums and private collections in the United States and Europe. A number of items, including recently discovered murals and artifacts, have never been exhibited in the United States before.

Strolling among the marble busts, bronze statues, mosaics, silver tableware and colorful wall paintings, one cannot help but feel awed by the sophisticated taste and sumptuous décor that the imperial family and members of the aristocracy brought to the creation of their country houses. It’s almost enough to make one forget that it all came to an end with the devastating eruption of Mount Vesuvius in A.D. 79.

We do not know how many of the estimated 20,000 residents of Pompeii and more than 4,000 inhabitants of Herculaneum perished, but we do know a great deal about how they lived.

In their maritime pleasure palaces the elite partook of opulence and relaxation as a respite from the business in which they engaged in the city. These retreats had everything one could desire to exercise the body, mind and spirit: gymnasia and swimming pools; columned courtyards with gardens watered by an aqueduct built by the emperor Augustus; baths warmed by fire or cooled with snow from the peak of Vesuvius; libraries in which to read and write; picture galleries and extravagantly painted dining rooms in which to entertain; loggias and terraces with sweeping vistas of the lush countryside and the resplendent sea.

High-ranking Romans followed the lead of Julius Caesar and the emperors Caligula, Claudius and Nero, all of whom owned houses in Baiae (modern Baia). Augustus vacationed in Surrentum and Pausilypon (Posillipo), and bought the island of Capreae (Capri); his son Tiberius built a dozen villas on the island and ruled the empire from there for the last decade of his life. Cicero had several homes around the bay (he retreated there to write), and the poet Virgil and the naturalist Pliny also had residences in the area.

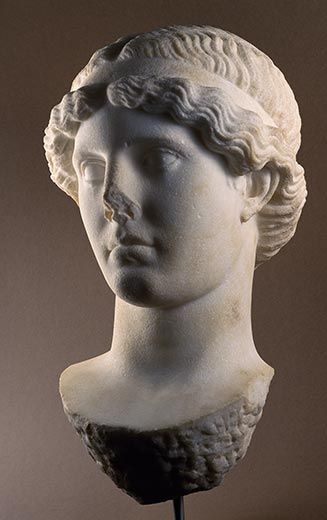

The show begins with images of the owners of the villas—marble or bronze busts of emperors, members of their families and private individuals such as Gaius Cornelius Rufus, whose sculpted likeness was found in the atrium of his family’s house at Pompeii. A fresco of a seated woman lost in thought is believed to portray the matron of Villa Arianna at Stabiae, about three miles east of Pompeii. Another woman is shown admiring herself in a hand mirror that resembles one on view in an adjacent case. The back of the mirror on display is adorned with a relief of cupids fishing (perhaps to remind its user of love as she applied her makeup and donned gold jewelry similar to the bracelets and earrings that are also on view). Nearby are furnishings and accouterments such as silver wine cups embellished with hunting and mythological scenes; elaborate bronze oil lamps; figurines of muscular male deities; frescoes of opulent seaside villas; and representations of delicacies harvested from the sea—all reflecting the owners’ taste for luxury.

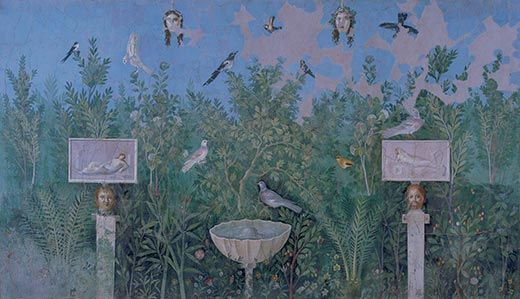

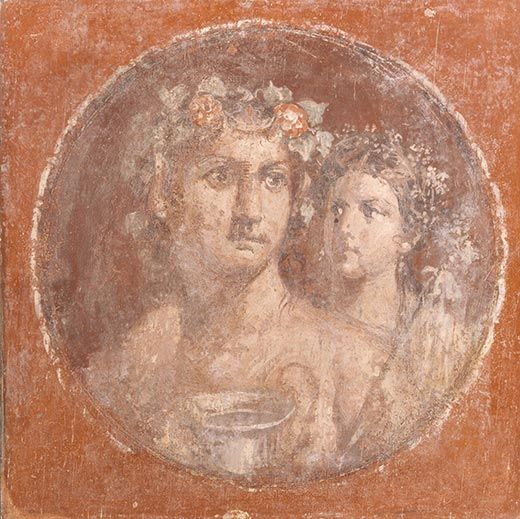

The next section of the exhibition is devoted to the Roman villas’ colonnaded courtyards and gardens. Frescoes depict lushly planted scenes populated by peacocks, doves, golden orioles and other birds and punctuated with stone statuary, birdbaths and fountains, examples of which are also on display. Many of these frescoes and carvings reference the fecundity of nature through depictions of wild animals (a life-size bronze boar attacked by two dogs, for instance) and of Dionysus, the god of wine, accompanied by his lascivious companions, the satyrs and maenads. Other garden decorations allude to more cerebral pursuits, such as a mosaic of Plato’s Academy convening in a sacred grove.

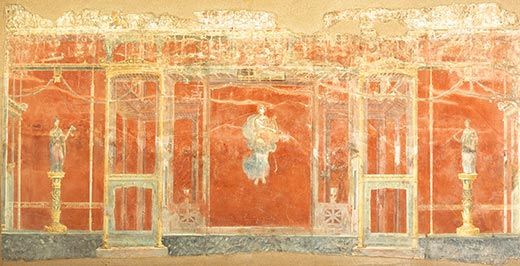

One of the highlights of the show is the frescoed walls of a dining room (triclinium) from Moregine, south of Pompeii. The frescoes were removed from the site in 1999–2001 to save them from damage due to flooding. In a coup de théâtre, three walls form a U-shaped reconstruction that allows visitors to be surrounded by murals showing Apollo, the Greek god of the arts, prophecy and medicine, and the Muses. The depiction of Apollo is an example of the most crucial theme of the exhibition: the Romans’ abiding taste for Greek culture. “They were lovers of what was to them—as it is to us—‘ancient’ Greece,” explains Carol Mattusch, an art history professor at George Mason University and guest curator of the exhibition. “They read Homeric poetry, they loved the comedies of Menander, they were followers of the philosopher Epicurus, and they collected art in the Greek style,” she says. Sometimes they even spoke and wrote Greek rather than Latin.

Cultivated Romans commissioned replicas of “old master” Greek statues, portraits of Greek poets, playwrights and philosophers, and frescoes picturing scenes from Greek literature and mythology. One of the frescoes in the exhibition depicts the classic group of Greek goddesses known as the Three Graces, and a beautifully rendered painting on marble shows a Greek battling a centaur. Also on view are a life-size marble statue of Aphrodite that emulates Greek art of the fifth century B.C. and a head of Athena that is a copy of a work by Phidias, the sculptor of the Parthenon. These expressions of Hellenic aesthetics and thought help explain why some say that the Romans conquered Greece, but Greek culture conquered Rome.

And alas, a volcano and the passage of time nearly conquered all. The cataclysmic eruption of Vesuvius entombed Herculaneum in a flow of lava and mud and spewed forth a mushroom-like cloud of debris that buried Pompeii in pumice stones and volcanic ash. Pliny the Younger wrote an eyewitness account of the eruption from across the bay in Misenum: “buildings were now shaking with violent shocks….darkness, blacker and denser than any night” and the sea “receded from the shore so that quantities of sea creatures were left stranded on dry sand” as flames burst from the volcanic cloud. His uncle Pliny the Elder, admiral of the imperial fleet based at Misenum and a naturalist, took a boat to get a closer look and died on the beach at Stabiae, reportedly asphyxiated by toxic fumes.

The final section of the exhibition is devoted to the volcano, its subsequent eruptions throughout the 17th century, and to the impact of the rediscovery and excavation of Pompeii and Herculaneum. The Bourbon kings that ruled Naples in the 18th century enlisted treasure hunters to tunnel into the ruins in search of statuary, ceramics, frescoes and metalwork. Their success led to later archaeological excavations that revealed nearly the entire town of Pompeii and the remains of Herculaneum and of country villas in the surrounding area.

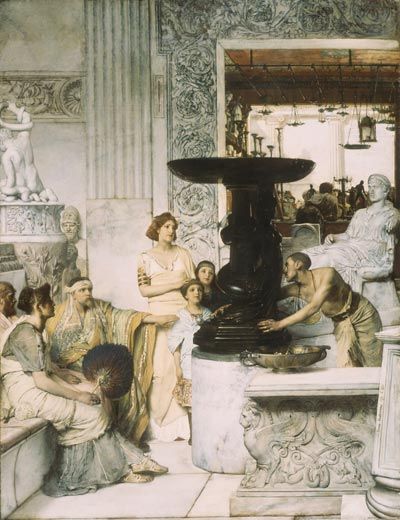

The discoveries drew sightseers to the region and spawned an industry for reproductions of antiquities along with a Pompeiian revival style in the arts. An 1856 watercolor by the Italian artist Constantino Brumidi shows his design for the Pompeiian-style frescoes that grace a conference room in the United States Capitol, and an imaginary scene, painted in 1874 by the British artist Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, depicting a sculpture gallery from antiquity, pictures actual objects found in the excavations of Pompeii and Herculaneum, some of which are on view in the exhibition, including the spectacular carved marble table supports from Pompeii that served as models for desks in the National Post Office in Washington, D.C. Such objects epitomize the artistic excellence and fine craftsmanship the Romans demanded in the furnishing and adornment of their villas around the Bay of Naples. Leaving the exhibition, one’s thoughts turn inevitably to planning a trip to visit the archaeological sites near the Bay and experience first-hand the Mediterranean coast that has beckoned for millennia.

Jason Edward Kaufman is the Chief U.S. Correspondent for The Art Newspaper.