Sanjay Patel: A Hipster’s Guide to Hinduism

The 36-year-old pop artist and Pixar veteran brings a modern twist to the gods and demons of Hindu mythology

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Sanjay-Patel-Ramayana-Divine-Loophole-631.jpg)

Sanjay Patel arrives at the entrance of San Francisco’s Asian Art Museum, breathless. His vahana, or vehicle, is a silver mountain bike; his white helmet is festooned with multicolored stickers of bugs and goddesses.

Though we’ve barely met, Patel takes my arm. He propels me through dimly lit halls, past austere displays of Korean vases and Japanese armor, until we arrive at a brightly lit gallery. This room is as colorful as a candy store, its walls plastered with vivid, playful graphics of Hindu gods, demons and fantastic beasts.

“This is awesome.” Patel spins through the gallery, as giddy as a first-time tourist in Times Square. “It’s a dream come true. I mean, who gets the opportunity to be in a freakin’ major museum while they still have like all their hair? Let alone their hair still being black? To have created this pop-culture interpretation of South Asian mythology—and to have it championed by a major museum—is insane.”

The name of the show—Deities, Demons and Dudes with ‘Staches—is as quirky and upbeat as the 36-year-old artist himself. It’s a lighthearted foil to the museum’s current exhibition, Maharaja: The Splendor of India’s Royal Courts. Patel, who created the bold banners and graphics for Maharaja, was given this one-room fiefdom to showcase his own career: a varied thali (plate) of the animated arts.

“I’ve known of Sanjay’s work for a while,” says Qamar Adamjee, the museum’s associate curator of South Asian Art, ducking briefly into the gallery. At first, she wanted to scatter examples of Patel’s work throughout the museum; the notion of giving him a solo show evolved later.

“[Hindu] stories are parts of a living tradition, and change with each retelling,” Adamjee observes. “Sanjay tells these stories with a vibrant visual style—it’s so sweet and so charming, yet very respectful. He’s inspired by the past, but has reformulated it in the visual language of the present.”

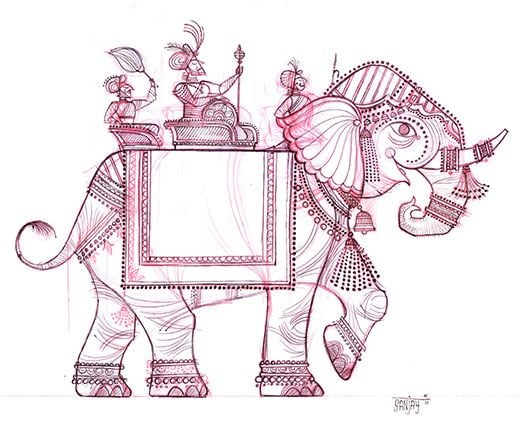

For those unfamiliar with Hindu iconography, the pantheon can be overwhelming. In Patel’s show, and in his illustrated books—The Little Book of Hindu Deities (2006) and Ramayana: Divine Loophole (2010)—he distills the gods and goddesses down to their essentials. Now he wheels through the room, pointing to the cartoon-like images and offering clipped descriptions: There’s Ganesha, the elephant-headed god, with his cherished stash of sweets; Saraswati, the goddess of learning and music, strumming on a vina; the fearsome Shiva, whose cosmic dance simultaneously creates and destroys the universe.

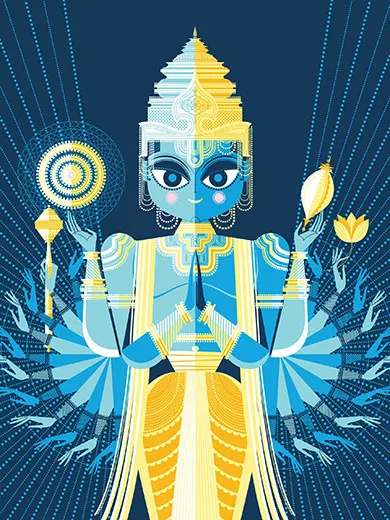

“And Vishnu,” Patel adds, indicating a huge blue-and-yellow figure. His multiple hands hold a flaming wheel, a conch shell, a flowering lotus and a mace. “Vishnu is, like, the cosmic referee. He makes sure that everything is in harmony.”

Vishnu, I’m familiar with. He’s one of the main Hindu deities, and often comes up in Patel’s work. Vishnu is the great preserver. According to the ancient Vedic texts, he will reappear throughout history to save the world from menace. Each time, he returns as an “avatar,” a word that derives from the Sanskrit avatara, meaning “descent.”

“An avatar is a reincarnation of a deity,” Patel explains, “taking human form here on earth. Vishnu, for instance, has ten avatars. Whenever something’s wrong in the universe, some imbalance, he returns to preserve the order of the universe.”

One might think, from Patel’s enthusiasm, that he grew up steeped in Hindu celebrations.

“Never. Not one.” We’ve relocated to Patel’s sunny apartment, on a hill overlooking Oakland’s historic Grand Lake Theater. He reclines in an easy chair; his hands are wrapped around a mug created by his partner Emily Haynes, a potter. “Growing up in L.A., we went to run-down little temples for certain festivals. But the kids would just play in the parking lot while our parents chanted inside. I learned about Hinduism much later.”

Patel, 36, was born in England. When he was a boy his family relocated to southern California. His parents have run the Lido Motel, along Route 66, for more than 30 years. They never had much money, but through the perseverance of a devoted high-school art teacher—Julie Tabler, whom Sanjay considers almost a surrogate mother—Patel won scholarships first to the Cleveland Institute of Art and then to the California Institute of the Arts (CalArts).

It was while Patel was at CalArts that representatives from Pixar, which has a close relationship with the prestigious school, saw Patel’s animated student film, Cactus Cooler.

“It’s about a cactus going through puberty,” explains Patel. “At a certain point, his needles start coming in—but because of the needles, he inadvertently chases away his only friend.

“Pixar loved it, and they recruited me.” Patel was hesitant at first. “I was in love with hand drawing, and the job involved a computer. But after getting some good advice, I did join the studio.” Despite his initial misgivings, taking classes at “Pixar University” gave him a real respect for CAD (computer assisted design). “The computer is just a great big box of pens, pencils and colors,” he concedes. “It’s another fantastic tool.”

Patel has been at Pixar since 1996. He’s done art and animation for A Bug's Life, Monsters, Inc., The Incredibles, Cars and the Toy Story films. The relationship works both ways. Pixar’s luminous palette and engaging, heroic characters ultimately inspired his own artwork.

Patel didn’t grow up enthralled with Hindu imagery, but the seeds were there. Six years into his Pixar career, he opened an art book and came across paintings from India. “The more I read,” he recalls, “the more I was drawn into a world of imagery that had always surrounded me. Before, it was just part of my family’s daily routine. Now I saw it in the realm of art.”

While Pixar is a team effort, Patel’s books are his personal passion. In The Little Book of Hindu Deities, he unpacks the mythic universe of ancient South Asia with bold, vibrant illustrations. A computer program massages his sketches into clean, geometric figures. It’s a cunning blend of East meets West, at a time when both cultures venerate the microprocessor.

Patel’s most ambitious book, so far, is Ramayana: Divine Loophole. A five-year effort, it’s a colorful retelling of India’s most beloved epic.

“Can you sum up the Ramayana,” I ask, “in an elevator pitch?”

Patel furrows his brow. “OK. Vishnu reincarnates himself as a blue prince named Rama. He’s sent to earth and marries the beautiful princess Sita. Through some drama in the kingdom, Rama, Sita and his brother are exiled to the jungle. While in the jungle, Sita is kidnapped by the ten-headed demon Ravana—and Rama embarks on a quest to find her. Along the way he befriends a tribe of monkeys and a tribe of bears, and with this animal army they march to Lanka, defeat the demons and free Sita.”

Just how popular is the Ramayana? “It would be safe to say,” Patel muses, “that almost every child in the Indian subcontinent would recognize the main characters—especially Hanuman, the loyal monkey god.”

In 2012, Chronicle will publish Patel’s first children’s book, written with Haynes. Ganesha’s Sweet Tooth tells the story of what happened when Brahma asked Ganesha—the elephant-headed god—to record another great Hindu epic, the voluminous Mahabharata. Ganesha broke off his own tusk to use as a stylus; the book imagines his various attempts to reattach it. (The Mahabharata’s plot, unfortunately, won’t fit in an elevator pitch.)

Among Patel’s many inspirations is Nina Paley, a New York-based animator whose 2009 film, Sita Sings the Blues, tells the story of the Ramayana from a feminist perspective. Patel credits Paley with giving him the inspiration to create his own version of the epic.

“Religion, like all culture, needs to be constantly reinterpreted to remain alive,” says Paley. “Sanjay’s work is not only beautiful—it updates and freshens history, tradition and myth.”

But interpreting religious themes can be risky, and Paley and Patel sometimes provoke the ire of devotees. Last summer, for example, a screening of Sita Sings the Blues was protested by a small fundamentalist group who felt the film demeaned the Hindu myths.

“It makes me sad,” Patel reflects. “I want to believe that these stories can withstand interpretation and adaptation. I want to believe that one person might have a pious belief in the legends and the faith, while another could abstract them in a way that’s personally reverent. I want to believe that both can exist simultaneously.”

A more immediate issue, at least for Patel, is the challenge of fame. Traditionally, Indian and Buddhist artworks have been anonymous. They arise from a culture where the artist is merely a vehicle, and the work an expression of the sacred.

“These characters have existed for thousands of years, and have been illustrated and re-enacted by thousands of artists,” he reminds me. “I'm just part of this continuum. So whenever the spotlight’s on me, I make a point of telling people: If you’re interested in these stories, the sources go pretty deep. I have nowhere near plumbed their depths.”

In the process of illustrating these deities and legends, though, Patel has been exploring his own roots. One thing he’s discovered is that the Hindu stories put many faces on the divine: some valiant, and some mischievous.

“One of the neat things my aunt told me,” Patel recalls, “was that the Ramayana is a tragedy, because Rama always put everybody else's happiness ahead of his own. But what’s interesting is that Vishnu’s next avatar—after Rama—is Krishna, the hero of the Mahabharata. Krishna is all about devotion through breaking the rules. He steals butter, has multiple lovers and puts his needs above everybody else’s.

“I was struck by the fact that—if you’re a follower of Hindu philosophy—there’s a time to be both. A time to follow the rules, and a time to let go, explore your own happiness, and be playful. That you can win devotion that way, as well.” The notion fills Patel with glee. “I think that’s really neat, actually,” he says. “It’s not just black and white.”

With this artist holding the brush, it could hardly be more colorful.